Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to ‘Behavioral Science for Brands’, a podcast where we connect academics and practical marketing. Every other week, Richard Shotton and I sit down and talk about the behavioral science that's powering some of America's most popular brands. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: And today, we're talking about New Year's, how to make great resolutions and how to keep them.

- MichaelAaron: Let's get into it. So, Richard. Making resolutions, keeping them. I don't know. When I talk about behavioral science, if there's a topic that comes up more frequently, then ‘how can I make a great resolution?’ ‘How can I keep it?’ It's a hot topic, I think, for all people as we come to the end of the year and we think about next year.

- MichaelAaron: And so you and I are practicing something that we're going to try for the upcoming year in 2024, which is we're doing some timely episodes, episodes that matter because of the part of the year we're in, and we chose New Year's because it's one of the biggest times where globally we all take a moment and we reset and we say, How do we want next year to look?

- MichaelAaron: How do we want to act next year? We found a study that said ‘36% of Americans will make a resolution in the upcoming year, but only 9% of them will actually keep that resolution. When you ask them six months or a year later’, I'm going to check the numbers here.

- Richard: And is it 9% of the 36?

- MichaelAaron: 9% of the 36, 9% of the 36 actually keep it.

- MichaelAaron: ‘23% will quit their resolution after the first week’. Another ‘43% quit by the end of the first month’. So by the end of January, almost one out of two people have lost their passion to keep that resolution. so these are things that when they made the resolution, it was really important to them. There was a study done by Forbes Health, and the top resolutions that Americans made were on improving their fitness, 48%, improving their finances, 38%, improving mental health, 36% losing weight, improving diet.

- MichaelAaron: All were top, top items. So we're talking about pretty serious stuff here. We're not just talking about, you know, small matters here. So if behavioral science can help people set better resolutions, keep their resolutions and improve their lives, well, then we want to talk about it. And then if there's something brands can learn from this, we'll make that application, too.

- Richard: Absolutely. So what strikes me from that is that figure that you said of only 9% of people

- MichaelAaron: actually keep their resolutions.

- Richard: So it is a really hard thing to do. Behavioral science won't make it easy, but it will make it easier. And there are lots of studies that people can apply.

- MichaelAaron: So, Richard, listening to these stats, making a real resolution and keeping it seems to be a daunting task.

- MichaelAaron: But we think that there's some behavioral science insights that can really give you a leg up. Do you want to talk about the first one?

- Richard: Absolutely. And it's not that these behavioral science biases will make change easy, but they can definitely make change easier and more likely to happen. So the first study I wanted to cover is a 2012 study, and it's by Steve Martin, who's at Columbia University.

- Richard: And so this study works with the British Health Department, the NHS. And one unique thing we have about health service here is it's three-point delivery,

- MichaelAaron: meaning when I walk into a medical appointment, there's no cost to me as a, as a person.

- Richard: Exactly. At no cost at the time. Anything you ever pay will come out of general taxation.

- MichaelAaron: I see. Different than America.

- Richard: Yes. Yes. Now, that has some positives, but one negative is if people don't pay for something, there is a danger that they don't give it the respect it deserves.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: And that manifests manifest itself as people not turning up for appointments.

- MichaelAaron: They make an appointment with the doctor, but they don't actually show up the day that.

- Richard: Exactly. Very, very costly. Got it. So Martin works with a chain of surgeries in Bedfordshire, and their current approach was when someone had had an appointment. The patient would come out of that appointment, go and see the receptionist to get their next day or time

- MichaelAaron: make sense.

- Richard: The Receptionist would give them a little bit of card with that time date written on and the patient would go away.

- Richard: So Martin monitors no-show rates in that setting, and then he attempts to intervention's first intervention, patient comes out of that original appointment, goes and sees the receptionist. The receptionist gives them the card with the time date on, but they hang onto that car for a second in the hand and just ask the patient to repeat back what time and date they're going to turn up.

- Richard: That intervention leads to a 3.5% reduction in no-shows

- MichaelAaron: something, but not a whole lot.

- Richard: Yeah, that's. But if you're an organization, of course, 68 million people, life is up to a happy lodge. Lot change.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: Final version. Patient comes out, the first appointment goes and sees the receptionist. The receptionist gives them a bit of card that's blank. And it's the patient who writes down the date and time of the next appointment.

- Richard: Now, in that set up, there is an 18% reduction in no-shows. The all the

- MichaelAaron: big impact.

- Richard: Massive impact. Yeah. The argument from Martin is that one of the strong drivers of human behavior is a desire to be consistent with our past selves. But we only tap into that bias if that commitment is made actively, either we write it down or we state aloud to other people what we're going to do.

- Richard: That finding definitely applied in the world of resolutions.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, and I think they're both halfs matter. Writing it down is about saying actively, I see myself doing this and I'm actively committing to it, and then by committing to it out loud to someone else or making a commitment with other people hearing it.

- Richard: Yeah, we recognize there will be reputational damage if we don't stick to that behavior.

- Richard: That's very different from internally thinking to yourself, I'm going to turn up to an appointment or I'm going to know so many chips.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, Yeah. And so if we were to extrapolate this study to how some might use this to make better resolutions for themselves, this New Year's, what would what would we say?

- Richard: Three things. Tell other people how you're going to change your behavior.

- Richard: Write down what you're going to do differently and maybe think about using a website like Stick there’s an American website called Stick STIKK.COM. And there you can make public pledges to change your behavior. So people can read those pledges and you'll feel beholden to them.

- MichaelAaron: And to me, that's like positive social pressure. It's not it's a good thing that others heard you say it and then you feel that you've got to make that commitment.

- Richard: Yeah. You're not trying to do something different to what you want. You just want to make your behavior match your your desires.

- MichaelAaron: Perfect. Perfect. Okay, well, let's then let's build on that. Let's talk about a second behavioral science insight that can help us here.

- Richard: This study was originally done to stop no-shows at doctors. If you run a chain of restaurants, you could use this principle when you are speaking to your customers, speaking to the diners, and they've booked their original

- MichaelAaron: reservation.

- Richard: Reservation, say to them, you know, will you let us know if you aren't going to be able to turn up? Don't accept silent assent. Leave a pause. Wait for them to

- MichaelAaron: affirm

- Richard: exactly. And then you're tapping into this idea of public commitments. So I think there's lots of ways small businesses could apply these principles.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. And what seems like a simple idea, you can almost naturally see how you skip over it.

- MichaelAaron: Well, we can print the card automatically. Or we can or we can have a text message that reminds them all good ideas. But we missed the opportunity to take advantage of this behavioral science insight.

- Richard: Absolutely. It's it's a danger with many of these studies. It feels like such a small intervention. People might think it has a trivial impact, but there's a repeated finding that even small interventions can have large impacts.

- Richard: So ignore this one at your peril.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, I just to underscore that point, it's easy to ignore the repeated academic findings that continuously prove this. And just to say, Well, we're going to do something else anyway. So what we're really trying to underscore in this episode is you say skip it at your peril. I say, you know, either you believe that the data can teach you something or you don't.

- MichaelAaron: And so, so long as you believe the data has a meaningful story to tell, you got to believe.

- Richard: And I would have no problem with a Brand saying, okay, well, wait a minute, this study was done with doctors. I run a fish restaurant. These are very different things. That's an absolutely defensible position. But the logical thought shouldn't be why I'm going to ignore this study.

- Richard: It should be. I'm going to try and revisit it. Yeah. Yeah. Get one receptionist to do 50% of the calls in one way and of course the other. Maybe the academic study isn't perfect. Your business. Don't ignore it, retest it in your unique situation.

- MichaelAaron: And if you do drop us a line, we'd love to hear. We'd love to hear your results.

- MichaelAaron: Cool, Okay, so one thing we can learn is that by making it public, by stick, by writing it down and saying it out loud to others, we get this positive social pressure. We get this this first fact. What else can we relay to folks that want to make a New Year's resolution and keep it?

- Richard: Second study, I think’s really useful is one from the University of Pennsylvania psychological in done very similar time, I think, to the year before Martin's studies.

- Richard: This was done in 2011 and Rozin is interested in the difference between motivation to change behavior and ease of changing behavior because he says there's two different ways to get someone to change, make them want to, or make the behavior they're trying to follow a bit easier to do. So he works with cafeteria, I thinks it’s the university cafeteria, and every week they alternate how they serve the vegetables in the easy condition...

- Richard: The vegetable bowls are shifted ten inches closer to the, you know, the kind of cafeteria path and the serving receptacle is a big spoon. In the other weeks, the whole condition, the bowls are pushed ten inches away and the spoon is replaced with a pair of tongs. Hmm.

- Richard: And Rozin finds the volume of vegetables consumed between those conditions varies between eight and 16% depending on the particular vegetable.

- Richard: Let's stop and think about that for a while. These are trivial bits of friction. I've got you ten

- MichaelAaron: type of utensil and inches closer or further,

- Richard: yet having a large effect on behavior that finding the friction is a really important part of what people do is something that's found again and again and again. And it runs counter to how most people think you should change behavior.

- Richard: Most people underestimate the importance of friction, and they overestimate the importance of desire and motivation. So think about this in a personal health context. We might think the way to exercise more is to read loads about the benefits, get pumped up, get enthused. What Rozin would say is actually, it's about making the change. You're trying to do much more straightforward, much simpler, much easier.

- MichaelAaron: Put your running sneakers at the side of your bed so that when you wake up in the morning, you put them right on something like that.

- Richard: Exactly. So for me, my weakness healthwise is often a beer in the evening or bags of chips. When I sit down to watch a TV show or the application of this principle would be if you have them in the house, you're going to eat them.

- Richard: It's so easy to go and get them, you know, I don't buy them on your weekly shop. You can always walk a couple of minutes down to the local store if you really, really want them. But the argument about this power of friction is you probably want to be on as many occasions, so keep the junk food out of eyeline.

- Richard: Hide it away. Best of all, don't have it in the house. That will have more of an effect than trying to bolster your willpower.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, I mean, this is a really, you know, really critical point, which is that if you want to change your actions, either decreasing the friction to do the positive thing or increasing the friction to do something that you know is worse for you, then then do that.

- MichaelAaron: And so you made the point, don't even have the junk. First of all, don't have the junk food in the house. When we were prepping for this episode, we talked about a little conundrum with that, which is that if I'm in the store and I really want that bag of chips, why is it easier to not? But, you know, why should it?

- MichaelAaron: Why should we believe that it's easier to not just buy the chips? And we had an interesting conversation about this. Go ahead.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. I think that is a repeated critique of emphasizing friction. But there are some wonderful studies by Read, I think, to the University of Warwick now, which suggests that we behave very differently when it's about consumption in the now to consumption in the future.

- Richard: So that feels a bit wooly. The study make it clear 1998 Read’s in Denmark, and he runs an experiment with a business 200 employees is split into two groups. First group, he says, Here's an apple and a bar of chocolate. You can pick whichever you want and you can eat it. Now. And when he makes that offer, a vast majority of people go

- MichaelAaron: he says 70%,

- Richard: 70% Chocolate, I think it was 30% Apple.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: Next group, same chocolate and apple. But this time he says, pick what you want and I'll bring it to you in a week's time. And now you have an almost exact flipping. I think 75% go for the apple 25 the chocolate. The argument here is when we are picking for now, we we essentially respond to what based as always, what's tasty, what's going to be enjoyable.

- Richard: When we're picking for our future self, we revert, well, what should we do? It's much, much easier to behave in a healthy, responsible way if we're picking for our future self. So absolutely, I do think this is a a finding that can be can be applied

- MichaelAaron: and you can keep extrapolating this better to plan your shopping list at home with what you want to do.

- MichaelAaron: And then when you get there, better to plan to buy the things that are the healthiest versions of yourself. All of these compounds so that when you're in the moment sitting down for TV, at the end of the day, you've already done the hard work in advance to have the right things in the house, making it that much harder to make the unhealthy choice you did not want to make.

- Richard: Absolutely. And if anyone's disagreeing with a study and thinking, oh, it doesn't apply to them. I think there's a really clear personal version where you can see this happening. You know, when you go out with work for a big dinner sometimes and they make you pick your meal beforehand. Yes. I'm sure people will remember that experience where a week before you think I want the chicken or the salad.

- Richard: And when you actually got one, I ordered the bloody steak. Yeah, Yeah. That's what I actually want. And it's that's the saying that's the difference happening. You know, our future self and our present self behave in a different way and you can use that to your advantage.

- MichaelAaron: I love that. And I think even the language you just said, what I really want is the steak, but it's what I really want that minute, not what I really want for my future health, you know?

- MichaelAaron: And so just separating those, disassociating the ‘what I want now’ with the ‘what I want for my plan’, for my resolution is a big insight that folks can use to make better resolutions but keep them. Yeah.

- Richard: Yeah. I think you said at the beginning that the main areas people were making resolutions about were health and finance. We talked a lot about health.

- Richard: I think finance is one way you could apply this principle. If people are listening now, don't, you know, necessarily put money into a savings account, be second, think about setting up a standing order for two months time. If you're thinking about giving up money in two months time, it feels so inconsequential. It doesn't feel like it matters. If you think about putting money into savings account now, it feels tangible and painful.

- Richard: So you can apply this in personal health. You could apply in personal finance.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, maybe you can make a connection. See? See if you can make a connection. When we did our episode on Clear Pay and Afterpay, we talked about how the pain of payment now is made much less by paying over four or six weeks with no interest.

- Richard: Yeah, that's a very similar thing. So there's a study there. I think it was Liam Delaney. We talked about that. I'm sorry. Yes, it was at the University of Stirling at the time. And it gives people choices. Things like, Do you want to pay me £13 now or £16 in a month time and you have 60% of people picking the £60 in a month's time.

- Richard: That's an APR of 1,099%. It's an astronomical APR. But again, it goes this point of I'm worried about current me Yes, future me someone else's problem. So you can apply this principle to encourage you to save money or what plant and clip I do is encourage you to spend more more money. Same principle can be applied in different ways.

- MichaelAaron: We're going to go to a break. And when we come back, we're going to talk more about setting great, great resolutions and keeping them. But I think a big theme from the first half here is you can make a resolution based on what you want your future self to be, but there's a lot of action that you can take to make that resolution more likely to have outcomes.

- MichaelAaron: It's not just making the intention, it's about doing the actions to really make it much more likely that you can have success. All right. So let's head to break, and when we come back, we'll talk more about this.

- AD: Behavioral science for brands is brought to you today by Method one, recognized as part of XenoPsi Ventures as one of the fastest growing companies in America for the second year in a row.

- AD: Method one Builds digital first marketing ecosystem items for brand growth. Their behavior change experts who bring science to the art of persuasion with deep disciplines in many brand categories reach out to method one at method1.com to start leveraging the power of behavioral science in your marketing or advertising.

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to Behavioral Science for Brands. And today, Richard and I are talking about making New Year's resolutions and how to keep them something that there's a lot of general interest in how behavioral science can help.

- MichaelAaron: So we're back from the break, Richard. And we were talking about, you know, what else can we share with listeners that give them the best chance to make a New Year's resolutions that are really going to stick beyond these dismal numbers? 9%, you know, only 9% get it to stick for very long. You know, 48% give up by the end of the first month.

- MichaelAaron: So what else do we have for people to consider?

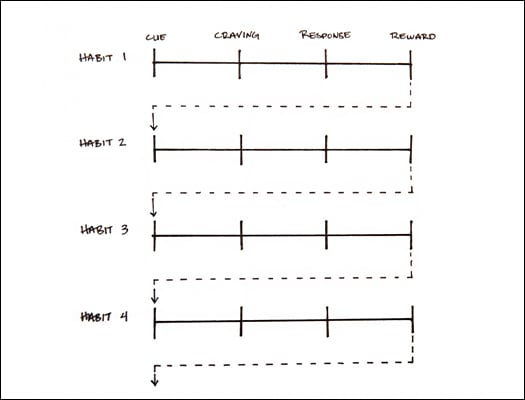

- Richard: So the third and final idea from Bible science is around the need for a cure, a trigger. So there's an argument behind the science. The motivation alone is not enough to change behavior. That's a necessary but not sufficient condition. What you need to do is attach the behavior you want to do to a particular time or place or mood.

- Richard: And there's some lovely work by people like Sarah Mile at the University of Bath that backs up this idea. We've previously talked about this with relation to brands like Snickers, brands like Kit Kat, where they attach consumption to a break or to feeling hungry, but you can apply that principle to yourself when you're thinking about personal behavior change.

- Richard: The argument here would be if you want to do more exercise, let's say you want to do press ups, don't just say vaguely angry. 10% today say

- MichaelAaron: in America. Push-ups. Oh yes. It’s The same thing. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

- Richard: Yes. I'm you would say I want to do my push-ups after I brush my teeth or after I've had my morning coffee.

- Richard: You attach the habit. You want to start with an existing habit. Some people call that habit stacking and it's a really, really simple technique, but one that increases the probability of success.

- MichaelAaron: And the reason from behavioral science, It does. It is because it aligns the the intention you have with the trigger. So when I brush my teeth, I now have it stack something on top of it, and I'm much more likely to do the next thing because I'm already brushing my teeth because

- Richard: otherwise you’ve just got this vague, nebulous desire to do something.

- Richard: You need a moment where that desire is converted into action. And it's the presence of a time like the morning coffee or the tooth brushing that will bring those desires to the forefront of your mind and remind you to act in the way that you want.

- MichaelAaron: And there's a lot of frameworks for how you can take behavioral science and the body of work that exists and apply it for yourself, apply it for brands to use.

- MichaelAaron: And we often in our consulting use the easy method, which is which was initially pioneered or codified, I would say you would say, by the United Kingdom's behavioral science team, the nudge unit and in the U.K. But BJ Fogg has a model that feels like it's very close to what we're talking about here. And he has a three-part model.

- Richard: Yep,

- MichaelAaron: I'm going to let you get in

- Richard: So he's changed the meaning of the initials, but it's either‘B’ equals mat or ‘B’ equals map.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: And it's essentially behavior occurs when motivation is greater than difficulty when a trigger. Right.

- MichaelAaron: From motivation, ability and trigger.

- Richard: Yeah.

- MichaelAaron: So motivation is know these based motivations, fear and pain, pleasure every day.

- Richard: So I think that what he's saying is motivation is how motivated. So if something is easy to do, you can have a medium level of motivation. I said when the trigger like toothbrushing comes along, if there's media motivation and it's very easy to do, you'll do it. Or if the behavior in front of is hard, but you have a huge amount of motivation when the trigger occurs, then it will it will occur.

- MichaelAaron: And in either of those instances, the formula is behavior change comes from the combination of those, three behavior, ability and trigger. And so we can we can put that in the show notes that we give out. But the point is that there are these other behavioral science formulas, other behavioral science approaches that can help you think about this more directly.

- Richard: Yeah. The interesting thing is that you've got all these different frameworks that you go by, the insights team's model you've got come from Season Mickey, an earlier version of the Insights team. And you've been out there all models to try and slice and dice the existing database of experiments, right?

- Richard: So each has their own strengths and benefit.

- Richard: I don't think any is perfect. Part of it is subjective. Which one do you find easy to use? I love East as a model. Think it's so straightforward and simple. Are the people for comedy or PJ folks and this element of subjectivity and trial and error?

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. And so when you're applying this for brands and for marketing and advertising, good to learn the models and think about them.

- MichaelAaron: When you're trying to apply this to your own personal setting a New Year's resolution and sticking to it, there's a few books that you and I have really liked that we think do a good job. BJ Fogg has ‘Tiny Habits’ and maybe even more direct and even more directive is ‘Atomic Habits’.

- Richard: Yeah, that's by. James Clear. So a lot of the books that are out there are written by academics.

- Richard: Yes. And just because you're doing research doesn't mean you're a brilliant writer. And if someone has done their own experiments, they tend to overemphasize them. The great thing about James Clear is, I think he has a journalistic background, so he's a brilliant writer, and because he's not exacting research, he is very evenhanded and very eclectic.

- Richard: And in the studies he picks and he has a real gift of coming up with either anecdotal stories that bring those experiments life and show people the the practical uses. So if there's one book about how to excel, I'd recommend it Always be Clear’s.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. We're not we're not giving more homework after coming in and listening to our podcast.

- MichaelAaron: But if it's an area of interest, if it's something you really passionate about,

- Richard: yeah, place to go. And I think his book is written in such a way that it wouldn't feel like homework. Yeah,

- MichaelAaron: Very exciting. Let's summarize the key takeaways from today's episode for our listeners.

- Richard: Three key things. The first is the power of an active commitment.

- Richard: So that was the Steve Martin study. Either tell people the resolutions you're going to make have made, or write it down.

- MichaelAaron: Yep,

- Richard: and you're more likely to stick to them. The second key point is around Don't just focus on boosting your motivation. Think about making the behavior you want to encourage easy as possible. That was the Roseanne study. We repeatedly as people underestimate the impact of friction.

- Richard: And then the third study we talked about was cues and triggers and habit stacking. And that's the idea. Don't just say you're going to change behavior. Be very clear about the time or place for that behavior. Change is going to occur

- MichaelAaron: Tied to a trigger.

- Richard: Exactly. So if we think about those three things, imagine the resolution was a trilogy, more push ups, a day, public statement or active commitment.

- Richard: Tell people you're going to do, Oh,

- MichaelAaron: Tell my spouse, tell my best friends, tell someone,

- Richard: Write it down. That's the first part. Then the principle, make it easy. Maybe don't tell yourself you can do 50 a day. Start super simple. Maybe it's two, maybe it's five. Break it down. It's a really small amount to begin with until you get that habit embedded.

- Richard: And then the third and final part about the habit stacking, don't just say you can do five push-ups today. Say you can do five push-ups after you brush your teeth. Be very, very clear about the time and place it's going to occur.

- MichaelAaron: Very, very helpful. Thanks for sharing that. So how to wrap up today's episode rather than asking the cliché what action will you make?

- MichaelAaron: Can you share a story or an instance where you had a resolution that you wanted to do and then how you got it done? Do you have? are you one of the 9% that has made a resolution and stuck to it that you could tell everybody a little bit about it? I can do the same.

- Richard: I think many people have had kids will sympathize with...

- Richard: This one, which is for the first few years of their life, when they there's that sense of release and relief that the evening is now beginning once they've gone to bed.

- MichaelAaron: Yes. Yes.

- Richard: Stressful day for managing these things. And I think I'm fortunate. I feel that that moment with too many too much junk food, too much food. I struggled for a long time to try and break that I had.

- Richard: It was really embedded. I felt like the evening my spare time hadn't started until I had crisps or chips, as you say, and I kind of beer. I found trying to break that completely was really hard. So what I did was substitute those behaviors. So rather than having chips, I'd have some nuts, at least a little bit healthier rather than having a beer I’d have a fancy kombucha.

- Richard: Now you need that idea of rather than trying to break the habit, slip something else in. I found to work for me personally.

- MichaelAaron: And today, when you wind down at the end of the day, what percentage of the time are we? Are we achieving our goal here?

- Richard: Okay, I don't if my wife’s listening and how how much I can exaggerate.

- Richard: I think I do a reasonably successful, I reckon. Yeah. Two thirds of the time is successful.

- MichaelAaron: That sounds pretty good. I would say I always wanted to run a marathon and I didn't know how. And so I got a book that teaches you ‘How do you run a Marathon?’ And it says whether you've run for 2 minutes or 20 miles, it doesn't matter.

- MichaelAaron: You follow this method and it can work. And I was reminded of it when we were talking about our key takeaways today. You start by making an active commitment, telling people you're going to run a marathon, and then you break it down into really simple goals. Every day I'm going to run a little and each day I'm going to increase it a little or five days a week.

- MichaelAaron: I'm going to run, and each time I'm going to have a longer and longer run and then make the commitment to when you're going to do it. Every morning when I wake up, I'm going to start by going for a run or every evening as the sun goes down, I'm going for a run, whatever that is. I follow those things.

- MichaelAaron: And in 2005, I was able to run a marathon.

- Richard: Fantastic.

- MichaelAaron: From having never run before so mean. That was really an example of setting an intention, following a methodology and getting it done

- Richard: Brilliant.

- MichaelAaron: Well, Richard, we've broken the very taboo topic of setting resolutions and trying to keep them. I think I can speak for the both of us, We hope it's helpful to everybody.

- MichaelAaron: And until next time, I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

Episode Highlights

Motivation vs. Ease of

Changing Behavior

People see a higher chance of keeping their resolutions by making the behavior they're trying to follow easier to do. A study by Paul Rozin and his colleagues ran an experiment in the college cafeteria, in which they slightly altered the accessibility of various healthier foods and saw successful outcomes.

Decision-Making Now

vs. Future

Studies suggest when we make decisions for the immediate now, we respond to our base desires. But when we make decisions for the future, we choose the healthy, responsible option.

Habit Stacking

Rather than pairing your new habit with a particular time and location, you pair it with a current habit. For example, after taking off your work shoes, you immediately change into workout clothes.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.