Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: So welcome back to Behavioral Science for Brands, a podcast where we bridge the gap between academia and marketing. Every other week we sit down and decode the science behind some of America's most successful brands. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron:Today we're talking convenience Chinese restaurants and the danger of choice. Let's get into it.

- MichaelAaron: So, Richard, the food delivery industry that we know today basically didn't exist ten years ago when we were kids.

- MichaelAaron: Ordering food from a restaurant was almost a harrowing adventure. So what was it like in the U.K. growing up as a young boy and trying to get something ordered and delivered? What was that experience like?

- Richard: I think I know I grew up in the middle of nowhere, so there was no you know, you'd have to drive to the fish and chip shop.

- Richard: There was no way anyone was coming

- MichaelAaron: Do you call in and order in advance or?

- Richard: No, no, no, no, no. It was like a van thing that Father found.

- Richard: I mean, good luck doing that.

- MichaelAaron: And how about with your kids? Growing up? Was delivery a little different then?

- Richard: Oh, I mean, they are. They're heavy users of Uber Eats and Deliveroo.

- Richard: Yeah, I think they spent half their money on it

- MichaelAaron: in America, at least in suburban America, where I grew up in the eighties delivering. Here's what it was like to order a pizza. First, you would have to look up the phone number of the pizza place in the yellow book, you would find the yellow book phone number and you would call and it would ring and nobody would ever answer.

- MichaelAaron: When finally, someone at the pizza shop answered, You had maybe a 50% confidence that they actually knew what you wanted when you ordered it. Then they would hang up the phone and you have no idea how long it would take for the pizza to get to you. And when the pizza did arrive, you would have to pay in cash to which the driver would never have any change.

- MichaelAaron: So, I mean, this was a complex, inefficient and challenging system, which is why delivery was not a very popular way to get food in America for a very long time. Then comes food delivery services powered by the Internet and the ability to use apps in the cell phone to make it easier. And this really explodes in popularity during the COVID 19 pandemic, when people were shuttered in place and food delivery gave you a chance to get food from the outside world brought to your home.

- MichaelAaron: Let's dive in and specifically learn about Uber Eats. We've done an episode on Uber before, but we didn't. We really talked about the the ride sharing part of Uber. So let's talk a little bit more about Uber eats Uber eats is launched in 2014 by Uber. And the concept is they're using their drivers to now be couriers ferrying meals from restaurants to homes.

- MichaelAaron: They're doing this in their cars, scooters, bikes or even on foot. Today, as of 2021, Uber Eats is operating in 6000 cities across 45 countries. And Uber Eats grew massively because of the pandemic. It doubled its revenue going from 3.9 billion in 2020 to 8.3 billion in 2021. And to put that in perspective, Richard, Uber Eats did 8.3 billion in revenue in 2021

- MichaelAaron: That was 48% of Uber's overall revenue of 17 billion. So in a time where ridesharing was significantly depressed because of the pandemic, Uber was still thriving as a company. Because Uber eats currently, Uber Eats is the leading food delivery service in the world with over 100 million active users and partnering with 600,000 restaurants globally. So this is a big operation, clearly tapping into a desire that developed nations want to have to get food brought to them.

- MichaelAaron: But getting there and getting people to adopt a food delivery service is really leveraging a lot of behavioral science.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. I think it's a brilliant case study for behavioral science and they use a lot of different biases throughout the process. Prioritizing ease over appeal is is one broad area. I think we've touched on that quite large in other episodes.

- Richard: So the area I think we could focus on today is a subset of Uber Eats and it's how they design their menus. Now, the biggest issue they have to overcome when you pull up a burrito, you look at various different restaurants, is an idea called choice paralysis. So the original experimentation goes back, I think it was to the year 2000 and some work done by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: what they do, they recruit a fancy supermarket. America triggers, and they set up a stall selling jam. And sometimes that store has six different varieties of jam for sale. Sometimes there's 24 varieties. And the key findings are, first of all, the bat 28%. More people stop when there's that large variety of jam. Now, that fits with classical economics.

- Richard: The idea that if you give people a wide range of things to pick from something is more likely to grab their attention. It's more likely to fulfill the audience's needs. But the second part of the experiment was more interesting not looking at what was the best thing to stop people and get their attention, but what led to the greatest sales?

- Richard: And there they found the complete opposite. They found that there were ten times the level of sales when there was the table selling, they restricted a map jam. Just £6.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: So they termed this issue choice paralysis. Sometimes the paradox of choice is essentially the idea. If you give people so many options that the act of picking becomes onerous.

- Richard: People tend to throw out the hands, walk away, and they can't be bothered to deal with the hassle. Now that's an issue for Uber Eats as an entire entity and for every one of the individual brands that sits on that platform, because many of those restaurants will have hundreds of different items. So they have to get around this problem of choice proxies.

- Richard: The leper experiment I mentioned was extreme. I think it got some controversy because later studies couldn't replicate that ten fold variation in behavior.

- MichaelAaron: Hmm.

- Richard: But if we move from individual studies to what's the most powerful unit in behavioral science, which are Metro Analytics,

- MichaelAaron: which means this study of many analysis combined together.

- Richard: Absolutely. So an academic will look at all the high quality papers on this particular topic and see what became themes are.

- MichaelAaron: Hmm.

- Richard: And there was a recent metro analysis of choice prices done by Chernov. And what he found was a really interesting nuance for brands, which was it's not the amount of choice that's the problem. It's how you structure the choice. So you could just give people a long list of hundred items and they will be befuddled, irritated and not bothered purchasing.

- Richard: Or you could structure those lives in such a way that you make it easy for people to highlight one or two particular dishes. And that avoids the problem of choice paralysis. So, for example, there's the principle of the unrest of fact. We notice what's distinctive.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: So if you give people 100 items just coloring five or six in a different hue or boxing them or a different font that makes them easy to spot or social proof highlighting an item that is most popular.

- Richard: And we know that people tend to follow what they think the common course of behaviors. So if you go down through breach, you'll often see the most popular, you know.

- MichaelAaron: I actually did this. Yeah, I did this before the episode started. And I went through and I screenshotted some of the most commonly used things on ubereats free item.

- MichaelAaron: If you spend $40 or more, spend $20 and save $5, buy one, get one free. Number one most like number two, most liked really using as many delineations or monikers that they can to separate certain food items from the rest.

- Richard: Yeah. And I think part of the success of that is simple distinctiveness. You highlight one thing with whatever adjective around it and it become more popular because you've made it easy to spot that one.

- Richard: But the one that you mentioned around number one or number two choice, that idea of social proof, emphasizing popularity that has been shown to be very effective in the restaurant setting. So there is a 2009 study by a Duke University psychologist called Hanneman Fang. And he works with Chinese restaurants. And sometimes in the restaurant, they put one of the items as being checks, pick other diners or exact the same item, but it was referenced as most popular.

- Richard: And what he found is there was significant more sales when it was highlighted as popular rather than as a chef's recommendation. So it went from, I think, 13% of people picking the chef's recommendation. It was 20% who picked time when it was referred to as most popular

- MichaelAaron: when it had that moniker.

- Richard: Exactly. So if you are trying to design a menu and you want people to pick out, you know, maybe it's one that's got lots of margin for you, talk about how popular it is and it will become more popular still.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, it's interesting because I even noticed when I was preparing for today's episode, a lot of the buy one get one freeze on Uber Eats are on very high profit items. You know, French fries, chicken wings, where it's a very low cost to produce but high, high profit. We're selling buy one, get one free may not make much of a difference to the retailer anyway.

- Richard: Yeah, that is a nice bit of you're not going to go to McDonald's and not buy a burger or pizza restaurant. Knock out pizza, but you might

- Richard: skip the chick,

- Richard: skip the chicken wings. So that's the thing you need to focus your discount on. No, the reason that they're there anyway.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. And, you know, when you were talking about the Chinese restaurant menu in creating this moniker, it made me think of going to a nicer restaurant and getting that wine book.

- MichaelAaron: And when you look at the wine book, page after page of wines, that if you're not an expert in wine, becomes overwhelming, almost paralyzing.

- Richard: Yeah. I mean, I never thought about the wine book, but I wonder if the purpose of that is almost to make you feel so uncomfortable that you're grateful when this Amelia comes around.

- MichaelAaron: That's what I was going to say

- Richard: with these very high priced recommendations.

- MichaelAaron: Unless you take the Homer Simpson approach where he says of have your second least expensive wine, I don't want the cheapest wine on the menu. I just want the second, the second cheapest.

- Richard: Whether or not this is backed in data or science, but I've certainly heard people claim that that is the worst choice to go for because, you know, this is this is an example of game theory.

- Richard: Restauranteurs know that people go for the second cheapest one. So that's the one that they have the highest markup on. It's probably often you getting a better quality wine if you buy the cheapest. Certainly be the rumor that that

- MichaelAaron: this is game theory, not behavioral science, but fascinating nonetheless. So, Richard, as we think about the items that we've talked about that Uber Eats has used so far, these are all kind of statements of fact that get this money off top, you know, first most popular item, second most popular item.

- MichaelAaron: But that's not the only monikers they use. They also have

- Richard: I've never heard anyone say the word moniker so much,

- MichaelAaron: what shall we call it?

- Richard: The label.

- MichaelAaron: The label.

- Richard: Yeah.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. So we'll use a less a less hard to spell word. You know, you have this label of trending now or this label of popular or limited time. It kind of stretches.

- MichaelAaron: If you had to say, you know, the number one top selling item, that's kind of a statement of fact, assuming that we're not going to have people lying to their customers.

- Richard: Yes,

- MichaelAaron: but this trending, this popular kind of opens it up to give a little bit more flexibility for the brand to kind of focus on what they want.

- Richard: Yes. So. So you mentioned a few different tactics for ethically steering behavior. The one that I really like is that emphasis on hot right now or trending, because what that taps into is a nuance of social proof. So psychologists would call it dynamic social proof. And it's the argument that emphasizing momentum of popularity is as powerful or more powerful than just emphasizing scale of popularity.

- Richard: The most relevant study comes from Sparkman and Walton, who were at Stanford, and they did a study in 2017 where they work with a series of cafes in America. And as people go in to the cafe. Half of the diners on that table see a little poster which says three out of ten Americans make an effort to limit their meat consumption.

- Richard: So that message emphasizes meat free eating is a minority behavior. And in that set up 17% of people automate frame necks out of diners. The poster on their table has the same statistic. Basically, three out of ten bar is prefaced with In the last five years, more and more Americans are trying to limit their meat consumption. Now, three have

- MichaelAaron: they're making it a more positive association.

- Richard: Yeah, positive and emphasizing it's a growing number. So it's not just a small value. It's small, but growing.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: And in that set up, there is an exact doubling.

- MichaelAaron: Wow.'

- Richard: Meat free audience are up to 34% of people ordering meat free. So that use of trending and hot right now doesn't just as you say open up the use of it to a far broader set of behaviors.

- Richard: It's not just your most popular dish you can pick pick a fast growing and high margin dish. Actually think experiment suggest it might be an even more effective way than just talking about most popular.

- MichaelAaron: So picking up on that idea of margin, Richard, what are other ways that brands can use to get people to pay more for that for for higher margin items?

- Richard: There's a lot from behavioral science on that topic. There's an awful lot on the psychology of price and encouraging people to spend that a little bit more. Probably the broadest theme is the idea that when people view prices, they do so relatively not. Absolutely. So by that, I mean for dollars 99, for a tub of ice cream is neither good value or bad value.

- Richard: It depends on what you compare it to.

- MichaelAaron: Right.

- Richard: That's not speculation that you and I did a study last year, maybe before for consumer behavior.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: We recruited 404 Americans, split into two groups.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: First group saw a tub of Ben Jerry's ice cream for 399. And next to it was from Wal-Mart. So ice cream for 199.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: And when people were asked how good value they thought the Ben and Jerry's was, we saw that 52% of people thought it was good or great value. So 52%. Next set of people, completely fresh group. They showed exactly the same. Ben and Jerry's variety, same size, same price. But next to it is some super fancy halo top ice cream for what was it for 99?

- Richard: Right. A little bit more.

- Richard: Now, when that group are asked how good value they think Ben Jerry's is, you see a significant change. You know what, 77% of people saying it's good or great value has Interesting because it's exactly the same products. All that you've changed is the salient comparison set. So what that study suggests is your role as a marketer is to accept that people's mental comparison set your product is flexible.

- Richard: And if you can shift that mental comparison set to something that is more expensive on average people's willingness to pay will increase.

- MichaelAaron: Yes. You know, there's a there's a fascinating study about the size of coffee cups and people will choose the medium size, whether that medium size is ten ounces, 12 ounces or 16 ounces. So long as it's the middle size, they gravitate towards that.

- Richard: I think it might be a Dilip Soman study. Yeah. And one of the nice things he did at the end of that study was ask people what should be the middle one, like why it's the right size. You get enough of a jolt of caffeine, but it's not too big for my bladder. So people give these very rational explanations for purchase about caffeine and volume.

- Richard: But his study shows it has nothing to do with. It's about the fact that the

- MichaelAaron: the reason in question

- Richard: is given a bigger one and a smaller one is an option here.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. Fascinating, isn't it? So this is really interesting for Uber Eats and for menu design. But not everybody that's listening to the podcast are restaurant tours or working in brands in food service.

- MichaelAaron: So how can we take these lessons and apply it more broadly.

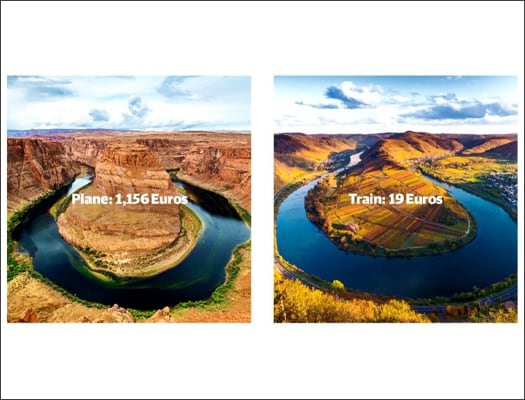

- Richard: That principle of prices being relative rather than absolute, that can definitely be put on in lots of different settings. The my favorite recent example is a brilliant German one from the German railway company Deutsche Bank, and what they tried to do in 2019 was encourage people to holiday at home.

- Richard: So they wanted them to visit German tourist sites rather than flying abroad. So imagine I'm living in Berlin. What they did is they scraped my Facebook data and they saw where I'd been researching. So maybe I'll be researching for a holiday in Colorado, and they would show me an image of a site, a tourist site in Colorado, and then they would overlay the flight price real time data from Skyscanner.

- Richard: And then in real time, they scraped Getty Images and Getty Images have hundreds of millions of pictures. They found a remarkably similar looking site in Germany.

- MichaelAaron: Brilliant.

- Richard: They serve that next to the Colorado tourist site and then they put the rail fare over the top.

- MichaelAaron: Obviously, less money.

- Richard: Yeah. Yeah. Obviously. Yeah. So to the order of magnitude of 50 or 100.

- Richard: Now, what's so interesting about that is what most marketers would have done if they were given the brief. How do I get people to holiday at home? Well, most people have done was just showed those Germans beautiful pictures of German tourists and told them the train fare.

- MichaelAaron: Right. No comparison.

- Richard: Exactly. And without the comparison, people will latch onto their own and the natural one, unless the brand states it is probably a tank of petrol and then 19 or €20 it would cost to get.

- Richard: The train isn't great value compared to the tank of petrol. But suddenly by throwing in this transatlantic flight comparison of a thousand plus euros, the €19 for the train feels like a rounding error by adding a comparison. Number, you can make your existing price appear tiny. Now that seems very, very simple, but people would only think of using it if they believe price is obviously relatively like an ice cream study showed.

- Richard: If you think people just weigh up the value of your product, the qualities it imbues versus the amount you're asking for, you would think the comparison is unnecessary. So once you accept prices are relative, not absolute, it becomes very, very obvious. Things stay until you've accepted that it would feel like a waste of time to do such behavior.

- MichaelAaron: And it would be our opinion that this applies as much to travel as it does to electronics purchases technology. It doesn't matter the category. It's the way consumers perceive value.

- Richard: Yes. Yes. So the real life example in train fares and this is really nice, I'll put up a link to the contagious article that has a lot of the numbers on on the performance that campaign.

- Richard: There are Tversky experiments, as you said, about electronics. There's the Dilip Soman experiment with coffee. There's is a failure study on popcorn. There is a really wide range of experiments that show the same point, and people will judge your prices partly on what you give them, but partly on what's comparisons that springs to mind. So make sure the comparison set that they are immediately thinking of is to your advantage.

- MichaelAaron: Right? And as advertisers and marketers, it's up to us to set the frame.

- Richard: Exactly. Exactly. You know, you see that thing with a really simple study we did? It doesn't take much. People are naturally grasping for a comparison set. You've just got to put a handy one in front of them.

- MichaelAaron: So Richard, at the end of every episode, we like to wrap up and summarize the key takeaways for our listeners.

- MichaelAaron: So what are the things we most want them to remember about this episode?

- Richard: First choice is not unambiguously good. There becomes a stage if you keep on giving people more and more variety, more and more different offerings. You have made the act of picking effortful and often people will avoid effort to be careful of access choice. Secondly, think about if you are giving people a large variety of different options, you can then use various different triggers or tactics to encourage you to pick the highest marginal items on a menu highlight and make distinctive the most expensive items.

- Richard: Make sure you label high margin items as popular or growing in popularity. And then finally, maybe the idea that has the largest potential effect. Remember the prices of relative not absolute. If you can shift your customers mental comparisons, have your products, you can change their willingness to pay by orders of magnitude.

- MichaelAaron: Great takeaways. Thanks so much for those.

- MichaelAaron: What an understatement to say that this is a episode that makes everybody hungry. Thinking about all the ways Uber eats gets food delivered. I thought we might do a fun trivia round. Richard, I've got some research from Uber. What is the number one most popular food item from Uber Eats this past year?

- Richard: Are we talking cuisine?

- MichaelAaron: We're talking actual food, actual item in the cart.

- MichaelAaron: The most popular item in the cart.

- Richard: I'll get French fries.

- MichaelAaron: Correct.

- Richard: I was to I was going to say, if it was cuisine, I was thinking it's going to be between burger and pizza and then French fries goes across multiple cuisine, something.

- MichaelAaron: So you got French fries is number one the second most popular? You got it is pizza. Can you guess the third most popular food item?

- Richard: Well, I would have said burger, but you would have given me that I'm going to get

- MichaelAaron: Skip.

- Richard: And that's I'm not going with Burger. I'm not wasting that answer. Most popular. I mean, it's got to be a drink. That's isn't Coca-Cola.

- MichaelAaron: Good guess. Sushi is our third most popular food item order on a Uber eats

- Richard: it is never have gone for it.

- Richard: I was always going make a joke. The thing I would do most is poke.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. Okay. Yeah. I kind of thought that would be we had a 20 year.

- Richard: Yeah. Yeah. I'm a me. I'm actually amazed by that.

- MichaelAaron: And that interesting last trivia question. Most popular day of the week to order Uber eats.

- Richard: Now, I've got to be honest because I think I saw or I think either you or someone mentioned this, I think someone's told me this.

- Richard: I think you told me it was Friday. So I think I've seen that on

- MichaelAaron: Friday. Is the answer Fair enough. He's an honest trivia contestant, folks. Honest trivia contestant Friday. Really fun. Thanks for tuning in today for this episode of Behavioral Science for brands I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton

- MichaelAaron: An average And if you've used price relativity to help grow your brand, we'd love to hear about it.

- MichaelAaron: Email us at [email protected] or drop us a comment on any of our social channels.

- AD: Behavioral Science for Brands is brought to you today by Method1–A digital-first marketing company that brings science to the art of persuasion. They’re behavior change experts who solve business challenges by creating meaningful connections with consumers. Method 1 has deep disciplines across many brand categories. To unlock behavior change that fuels brand growth - visit them at method1.com

Episode Highlights

Choice Paralysis

Research shows that it's not the amount of choice that's the problem, but how you structure the choice. Highlighting specific items, using distinct labels, and emphasizing popularity can help customers make decisions and increase sales.

Dynamic Social Proof

Highlighting that something is "trending" or "popular" can tap into dynamic social proof, indicating that a behavior is not only common but also growing in popularity.

Relative Pricing

Prices are relative, not absolute. By strategically framing products in comparison to more expensive options, brands can make their prices seem more reasonable and increase willingness to pay.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.