Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to Behavioral Science for Brands, a podcast where we bridge the gap between academia and marketing. Every other week we sit down and decode the science behind some of America's most successful brands and the campaigns that power them. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: Today we're doing milk mustaches and the messenger effect. Let's get into it.

- MichaelAaron: So, Richard, today we're talking about an American staple milk in almost every refrigerator in America. You open it up and there's a bottle of milk. How about in the U.K.? Is milk as omnipresent as it is in America?

- Richard: Yeah. Even though you've now got a number of pseudo milks, only milk, soy milk, whether it's still absolutely a regular feature.

- MichaelAaron: Plain old cows milk is a regular feature. And in America, so much of the success of Milk becoming an everyday staple really can be linked back to the California Milk Processor Board's 1993 campaign. Got Milk, Interestingly, and doing some of the research, the consumption of milk has been decreasing since the seventies. So even though consumption of milk is slowing, the goal of the milk campaign was to increase consumption, but also just to make sure it was a part of the American diet in such a big way.

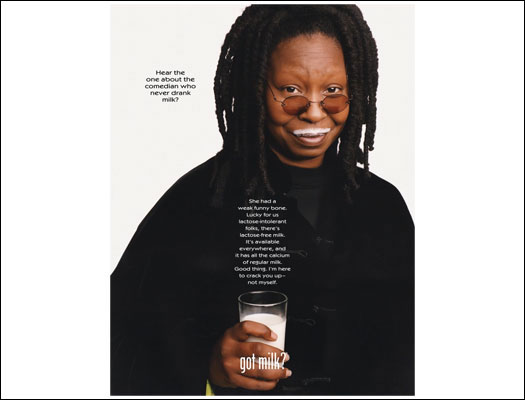

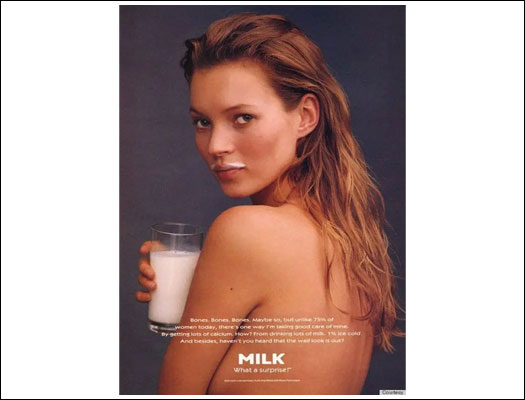

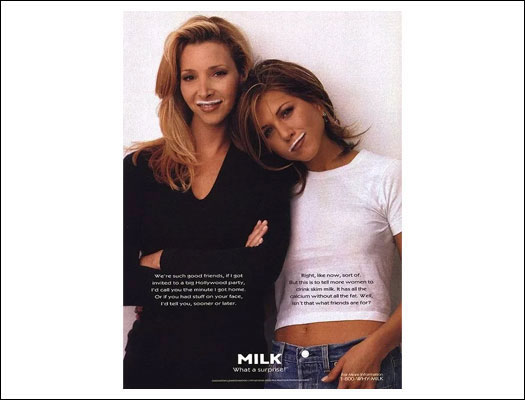

- MichaelAaron: So much of the success of milk can be attributed to the Got Milk campaign that was created by the California Milk Processing Board in 1993. The campaign features simple black and white images of people with milk mustaches accompanied by a question Got Milk or throw a bunch of the examples in the show notes. The original campaign was created by Good B Silverstein and partner, and the agency's creative director, John Steele, came up with the idea for the campaign after conducting a focus group with consumers.

- MichaelAaron: In the focus group, participants were asked to not drink milk for a week, and when they came back a week later, they were asked to describe how they felt. Many of the participants said they felt tired, irritable, had trouble concentrating. And so Steele realized this was an opportunity to create a campaign that would remind people the importance of drinking milk.

- MichaelAaron: So he came up with the idea for the milk mustache, which would be a visual reminder of what it was like to drink milk. The campaign featured over 100 different celebrities over its 20 year run. Everybody from Britney Spears to Beyoncé to Rihanna, Serena and Venus Williams to The Simpsons, Batman, Mario from Mario Brothers and the Powerpuff Girls.

- MichaelAaron: This campaign alone is estimated to have generated over $1,000,000,000 in sales for the dairy industry. So lots to think about. Lots to decode here. Where should we get started, Richard?

- Richard: I think the fundamental bias that they're using here is loss aversion.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: So most campaigns talk about what you gain by buying a lager or buying a pair of trainers.

- Richard: What's so interesting about milk is all of the ads focus on or a lot of the ads focus on what happens when you don't have milk, when there's an absence of milk. Now, that reminder of missing out taps into a deep drive of human behavior. So the original experimentation and loss aversion was done by Daniel Kahneman. But probably the simplest study to explain was one from Eli Aronson, who was a Harvard psychologist, and he ran this study in 1988.

- Richard: He went round and knocked on people's doors and tried to sell them insulation. And sometimes he said to the homeowners, if you take out the insulation, you'll save $0.75 a day. So focus on the positive. Other times, he focused on what they were missing if they didn't count insulation. He said, if you don't get insulation, you'll be wasting $0.75 a day.

- Richard: The key finding was that people were 50% more likely to take out insulation if they had heard about what they were losing out on, rather what they could gain.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: So there are repeated studies which show again and again that actually, contrary to how most people behave, it's often more effective to focus on what you're missing out on if you don't buy a product than what you gain by buying a product.

- MichaelAaron: What do you think the practical reason for that is? Human nature has more of a fear of losing out than, what, $0.75 a day to them? What do you think's causing that?

- Richard: I think there might be an element of it. For most of our evolutionary history, it probably made more sense to avoid catastrophic losses, the go for gains that the best you can have from the discovery of food source is a full stomach.

- Richard: The worst that you can get from

- MichaelAaron: death

- Richard: Yeah, right. Yeah. And that's a bit more final. So I think there's an asymmetric nature between loss and gain. And for a lot of human history, death was a reasonable or regular occurrence. So I think we're hardwired to try and avoid losses because we don't always recover from them.

- MichaelAaron: Mm. You know, thinking about this loss aversion more deeply, I think Silverstein and Partners really brought it to life beyond just the black and white images in a number of TVs, parts that really creatively made it feel visceral to the American public. One of the most famous spots that will be put in the show linked below is, I think it's titled Heaven or Hell.

- MichaelAaron: And you've got a 1980 businessman who gets hit by a bus or a truck and he wakes up and it feels like he's in heaven. There's, you know, white walls and a clock that is showing infinite time and cookies, delicious big chocolate chip cookies. And when he goes to open the refrigerator, the massive refrigerator, all he sees is cartons of milk until he finds out they're all empty.

- MichaelAaron: And it simply ends. And I think it taps into this like this sense of like, who wants to have a cookie without milk? I mean, it's an amazing, visceral spot, how it makes you feel when you don't have the ingredient that makes it all work together.

- Richard: And then when you put it that way, it's a reminder of how irregular that approach is.

- Richard: Virtually every brand out there talks about Bioproducts getting this benefit. It's a rare brand who taps into loss aversion, reminding people of what you don't have if you don't take out the product. Now, part of the success,

- Richard: I think, therefore, comes from the, you know,

- MichaelAaron: uniqueness

- Richard: psychological insight. The other half is you say you have this uniqueness. Now we know that one of the big drivers of memorability is distinctiveness as an idea called upon rest or the fact experimentation stretches back to 1933.

- Richard: We're hardwired to notice what's distinctive. So even if loss aversion wasn't as powerful as it was simply zigging when others zag makes fakes for a strong strategy.

- MichaelAaron: You know, in thinking about where loss aversion has been used in popular culture, it's hard to think of many examples. But one that comes to mind right away for me is Donald Trump's 2016 campaign, Make America Great Again.

- MichaelAaron: Now, at first blush, Make America Great is kind of a mediocre statement. I would say it's patriotic and it may be evocative, but Make America Great Again taps into this sense that we've lost something. Yes.

- Richard: Yeah. That I think is a very interesting example, because the single biggest political event in Britain's recent history was Brexit.

- MichaelAaron: They go

- Richard: There was an interesting commentary from the strategist behind the Brexit campaign's Dominic Cummings, and he talks about how the original slogan had been Take Control.

- Richard: So the idea being that it was the EU telling Britain what to do that was going to be the motivators to get people to vote to leave. But his involvement in the campaign was introducing one extra word, so it now became take back control. And that's according to lots of versions, much more motivating. Now, something that we have once had that we no longer have is powerful in a way.

- Richard: The simple up side isn't.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, you know, and both of those political examples make America great again and take back control. Tap into this sense of loss. They also strike me as a little negative.

- Richard: Yeah, that's a fair point. And I think what's really nice about Got Milk is that they avoid that through the use of humor.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah,

- Richard: most brands, I think, shy away from maybe being as negative as often.

- Richard: Political campaigning is.

- Richard: And what's so good about humor and we discussed this on the Economist episode, is that you can often convey unpalatable messages with a dash of humor in a way that just wouldn't be possible if you approached it head on.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, and it disarms the recipient of the message because when they hear it, they're first decoding the humor and then they're receiving the message behind the humor.

- MichaelAaron: So it gives them that, you know, it gives them a little space to take in the message. More palatable, I guess.

- Richard: Yeah, the great copyright behind the Economist ads. But it briefly said they've Abbott said directness has its place in advertising. But so subtly and bleakness, things you can't say literally can often be said laterally. I think that's the case with yeah, certainly The Economist Advertising, which she was directly referring to, but similar principle with Got Milk.

- Richard: If you bang on about how your customers will struggle without your product, it might feel a bit arrogant and a bit irritating. But you sugar that pail with a little bit of humor and it's much more acceptable.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, you know, you raise literal versus lateral applications. We can remind listeners what that means. And then I wanted to raise, you know, this idea of rational versus emotional.

- MichaelAaron: So let's start first with literal versus lateral application.

- Richard: So there I would say maybe The Economist is the best example. You don't go out and say you're fired if you don't buy The Economist. That would be a literal direct approach. The lateral approach is to wrap up that message in a small puzzle.

- MichaelAaron: MM hmm.

- Richard: I don't read the Economist mantra trainee or I've never read the Economist Management Trainee, age 42.

- Richard: So that second version is underlying at the bottom of it, saying the same thing, but it does it in a degree of flatulence, which makes it more palatable than the literal approach.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. Another example of literal lateral that we've used a lot is all old MP. Three players used to literally say 256 megabytes of storage space laterally.

- MichaelAaron: There's a thousand songs in your pocket.

- Richard: Yeah, right.

- MichaelAaron: It's a lateral application. So there's literal versus lateral applications in the Got Milk example. There's also this idea that they're making a more emotional connection rather than a rational connection. Yes, there's calcium in milk. Yes, there's your nutritional benefit, but that's not really what they're talking about in this campaign.

- Richard: Yes. And it's interesting you use that distinction of emotion and rational because that's something that comes up again and again in advertising. Best practice and the analysis of Lisbon and Peter Fehr, where they've looked at thousands of entries in the UK in sync with the IPA Effectiveness awards. They have shown again and again the campaigns that try and generate an emotional reaction tend to be more successful than those that aim for a rational reaction that try to rationally persuade.

- Richard: Now, the advertising industry, I think, often interprets that data to think, well, okay, we can be emotional by having tear jerking ads. But actually if you listen to some of the commentary, especially less benign, when he talks about emotions, he's often talking about that in the same way that people, scientists would. He's talking about the immediate response that a brand evokes.

- Richard: So what Got Milk is doing, I think is just repeatedly fuzing that link between an absence of milk and horror and bad outcomes. So it's not necessarily the pinnacles of joy or sadness, but creating this immediate reflexive link with absence of milk and unhappiness.

- MichaelAaron: And then in the black and white print ads and Got Milk with the milk mustache is a positive association, wouldn't you say?

- Richard: Yes. And I actually think, though, when you start moving onto the milk mustaches, which was a kind of later big development of the campaign, then I think you're moving to a different set of biases.

- MichaelAaron: Right.

- Richard: And what makes that campaign stand out is probably it's one of the most extreme uses of celebrities ever. I think you mentioned Bart Simpson wasn't Bill Clinton and in.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: You know, the ridiculous range of celebrities,

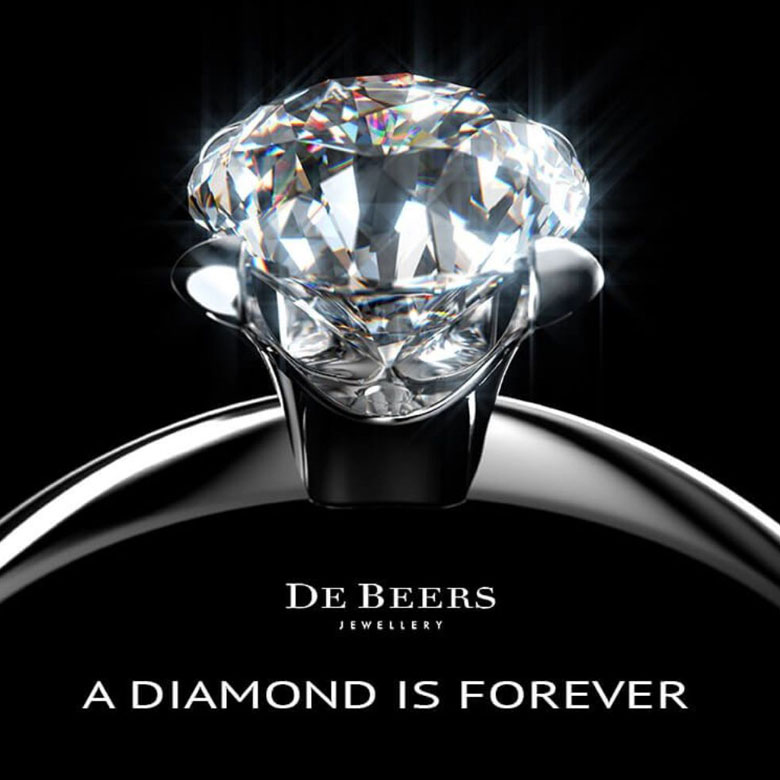

- MichaelAaron: they call that the messenger effect.

- Richard: Exactly. Exactly. So the original study and there's plenty more since this one was 1951 by two Yale psychologists called Hovland and Vice. And what they did was recruit 200 people. And they asked the participants their point of view on a topical matter. So some people were asked, for example, do you think a nuclear powered submarine can be built in the next 12 months?

- Richard: People would say yes or no. Then they would invite those participants back to their lab four days later, and when the participants arrive, there was a sheet of A4 waiting for them. And on that bit of paper there was a strong argument about why the participant was wrong. So if I've said yes, submarines can be built in the next 12 months with a nuclear engine, there would be an argument why that's just completely impossible.

- Richard: Now, the twist in the experiment was some participants saw that argument coming from a credible source. So, for example, Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist. Other people saw that argument coming from my low credibility source, like Crawford, the Russian magazine. Now, when the two groups then answered whether they changed their opinion, you saw a very stark pattern. 7% of the people who saw the argument from a low credibility source had changed their mind, whereas it was 23%, a more than three fold increase, 23%.

- Richard: For those who saw the argument from a high credibility source. Remember, this is exactly the same argument People are getting exactly the same words, exactly the same logic. But the big effect was who the message came from. So the argument here for the messenger effect is sometimes who says something is more important than what said? And I think it's that that's really used by the court milk in these later stages of the campaign.

- Richard: It's not the Californian opposite California milk processing board but

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: Yeah yeah various it was. It's not them that's telling you milk's amazing.

- MichaelAaron: it's Michael Jordan.

- Richard: It's Serena Williams.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And you know, it taps into a party's celebrity culture. That's not why they're famous. It's almost just that they're famous or that they were successful and that they're great athletes.

- MichaelAaron: And they say this right? So the messenger effect kind of just doesn't need to tap deeply into their credibility, just that they're recognizable and that they've made it and that they are a credible source to make the statement.

- Richard: Yeah, the the argument from later studies into the messenger effect is that tend to be three attributes that make for a powerful messenger.

- Richard: So it could be authority that Michael Jordan talking on basketball, it could be relate to ability. So maybe it's my you know, neighbor or someone who lives next door. And then the third one is neutrality. So it's that someone hasn't got an obvious vested interest for promoting a particular point of view. So I wonder if you get a kind of a blend of depending on who was the best being, you'd be bringing a blend of all three of those.

- Richard: And to a degree, if you're a soap star, you have an element of reliability. People think they know you, even if they've never met you.

- MichaelAaron: They think reality television in America.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. There's a certain degree of neutrality.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: And then, you know, authority. The interesting thing there is there is an idea called the halo effect, which is if someone is very good in one aspect of their lives or they're amazingly intelligent or they are amazingly good looking.

- Richard: We use that as a shorthand for all the other attributes. So if we think Michael Jordan's is an amazing basketball player, we assume he must be

- MichaelAaron: a good investor.

- Richard: Exactly. Yes. Yeah. And we often overestimate that spread that that creep of values. So just because he has no medical training doesn't know about the healthiness of milk, it's good enough for him.

- Richard: And he's an amazing sports star. Well, maybe some of that will rub off on us.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. It also brings to mind the concept of social proof, which we talked about a number of different episodes before, and that the social proof is more effective when it comes from people that are like me, which would be the authenticity play, right?

- Richard: Yeah. The famous study from Robert Cialdini was about using social proof to get people to reuse their towns and hotels and he found that if you said pleasure, use your talents, good for the environment. 35% of people did. So if you said please reuse your town, most guests so you have a 26% improvement in the right, 44% of people use their towns.

- Richard: But just as you say, the most successful test he ran was not just popular actor behavior amongst any other person. It was trying to tailor the message of popularity to a like minded person. So it was the final chat rooms that he ran the experiment and said, Please reuse your towels. Most guests who stayed in this room don't say an even

- Richard: That weak link being they were in the same hotel room before

- Richard: That boost did compliance. So up to there I think it was 49% of people reuse their towns 40% improvement in control

- MichaelAaron: that weak link being that they just happened to have stayed in the same hotel before but

- Richard: even that

- MichaelAaron: yeah

- Richard: little link to compliance further.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. Fascinating. So let's wrap up today's key lessons for our audience today. Richard, what are the big things we want them to take away?

- Richard: So the first thing is to appreciate what is often around the use tactic, loss aversion. Think not just about how you can emphasize the benefits of your products, but try and emphasize to people what they will suffer if they don't have your products. If that feels a little bit aggressive, a little bit hard sell, think about example of Got Milk and how they soften that message with a dash of humor.

- Richard: And then the final part is don't think that's all that matters is what you say. Think about who conveys your message and that they argue for the message effect is that can be often as important as the underlying message.

- MichaelAaron: Wonderful. So talked a lot about milk today. There's more milk today than ever before in history. Do you is there a favorite milk at the shot in the household

- Richard: where we divide here?

- Richard: My wife's a soy milk fan, and I think that's one of the worst tasting things, man to man. So I'd be plain,

- MichaelAaron: plain caramel

- Richard: skims or semi-skimmed.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, Yeah, we do a lot of we have little ones in our household, so we have lots of 2% milk and skim milk. But I'm newly engaged with almond milk.

- Richard: Okay.

- MichaelAaron: And but for the worries of how much water it takes to make an almond, I think it's pretty delicious.

- Richard: Each they're on each their own.

- MichaelAaron: Thanks so much for turning into Behavioral Science for Brands podcast, I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: If you enjoyed today's show, please give a good rating and leave a review. And if you're implementing behavioral science in your brand or company, we'd love to hear about it. Email us at [email protected]. or find us on social media.

- AD: Behavioral Science for Brands is brought to you today by Method 1–A digital-first marketing company that brings science to the art of persuasion. They’re behavior change experts who solve business challenges by creating meaningful connections with consumers. Method 1 has deep disciplines across many brand categories. To unlock behavior change that fuels brand growth - visit them at method1.com

Episode Highlights

Loss Aversion

The Got Milk campaign leveraged loss aversion by focusing on what people would miss out on if they didn't have milk instead of emphasizing the benefits of milk consumption. Studies have shown that people are often more motivated by the fear of losing something than the prospect of gaining something.

The Messenger Effect

The campaign's success can be attributed in part to the Messenger Effect. People are more likely to be persuaded by messages delivered by credible and authoritative sources. In this case, celebrities like Michael Jordan and Serena Williams lent their credibility to promote milk consumption.

The Halo Effect

The campaign benefited from the Halo Effect, where the positive attributes associated with a celebrity or authoritative figure extend to the product they endorse. People tend to assume that successful individuals are knowledgeable in various areas, even if there's no direct connection between their expertise and the product.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.