Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: So welcome back, everyone, to Behavioral Science for Brands, a podcast where we bridge the gap between academia and marketing. Every other week we sit down and decode the science behind some of America's most successful brands and the campaigns that power them. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: Today we're diving into diamonds, romance and the wheels of fortune.

- MichaelAaron: No, not a trashy romance novel. Let's get into it. So, Richard, we are getting a little romantic today. We're talking about something that most people think about for most of their lives. The moment they will get engaged to someone they love. And how will they show their love for that other person?

- MichaelAaron: Well, 100 years ago,

- Richard: 100 years ago, they could have done anything and bought a washing machine or giving someone a sapphire.

- Richard: It was not a case that everyone gave a diamond ring to their betrothed.

- MichaelAaron: And even today, not every country in the world does use a diamond ring. But the DeBeers Diamond mining company has made it a standard and has made it the expected for so many countries across the globe. So let's dive into a little bit about the history.

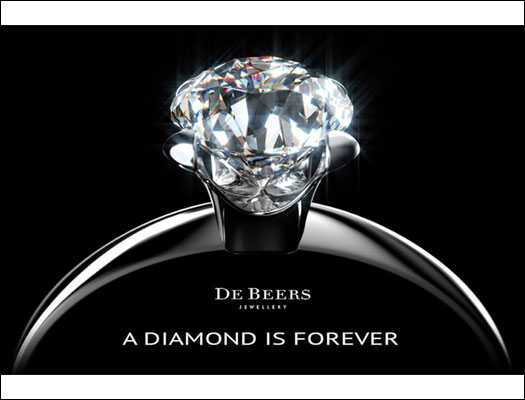

- MichaelAaron: We'll talk a little bit about the campaign and then get into the behavioral science about all of it. Debeers is primarily a diamond mining company, has been in business for over 100 years. Early in the 20th century, they realized they needed to do something to increase demand for the product that they're mining. So they launch a massive marketing campaign with the goal to change the way people think about diamonds.

- MichaelAaron: So they engage an air advertising agency and famously the air agency puts Francis Garrity on the account. It's the mid 1940s. The world was a different place. The advertising industry was a different place. So Francis Garrity, working in what can only be described as a man's world, was put on. Only women products because she was a woman were put up with De Beers as her main account.

- MichaelAaron: And when she comes up with the line, a diamond is forever. It was not universally accepted. It was not widely understood that it would be the winner that it was today. But thankfully, we in 2023 are in a different world where we're not just assigning women to work on female brands, and we are hopefully evolving past those that time.

- MichaelAaron: But the campaign is an undisputed success, one of the most celebrated campaigns of the 20th century. It helped the diamond industry to what it is today over $80 billion per year, with over 50% of all diamond sales coming from the United States. And just to be clear, the marketing and the advertising campaign that we're going to dissect today that has been central to the creation of a diamond as an engagement ring is not just a default.

- MichaelAaron: And in 2019, right before the pandemic, CEO of DeBeers, Bruce Cleaver, said that they would spend another hundred and $80 million in that year alone to continue to build the Association of Diamonds as the choice for engagement rings. So this campaign, Diamonds Forever is cited as one of the most effective marketing campaigns of all time. So certainly there's a lot going on here.

- MichaelAaron: If we take a look through a behavioral science lens, Richard, how can we start? How would we start to analyze it?

- Richard: Well, let's start with the line. A diamond is forever, I think, because it's been such a long standing line, because we've all heard it so many times, it has become normalized. But if you think about the individual words, it's quite a strange way of phrasing.

- Richard: And you wouldn't normally say a diamond is forever. You'd say a diamond lasts forever. But I think it's that linguistic quirkiness that actually makes it quite powerful because it introduces a little bit of difficulty to understand. And as we talked about a while ago on The Economist episode, if you make it really easy for someone to understand, they tend to forget the communications.

- Richard: It's that resolution that makes it more memorable. So that's not speculation. There's a brilliant Daniel Oppenheimer study, so he's a psychologist at Princeton back from 2010. It's a very simple study. He gives people a list of words and attributes to remember, and sometimes these are written in a very simple, plain font. Other times they're written in half straight from the strongly italicized, and he finds in that first group the easy to read from people rebate.

- Richard: Remember 73% of the information. Whereas in the hard to read setting they remember 87%. So you've got plots that are 14% up, an increase in memorability. So the first thing they do, and this is a tactic I think you see again and again with really powerful, really memorable straight lines is they add in a slight mistake. You could say that in a little bit of linguistic quirkiness to boost that memorability.

- MichaelAaron: And so when your mind returns to it, you remember it with the quirkiness. You remember it as the unique phrase it was.

- Richard: Yes.

- MichaelAaron: And then there's also something else happening here. The agency and De Beers at the time understood that an engagement is a real life moment, a milestone, and saying a diamond is forever is a little bit of a statement about your love for the other person.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. I mean that then you're moving to these ideas of some cost effects.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: Now, once you have spent a large amount of money or effort, what we really don't want to feel is that that money or effort has been wasted. So once we've expended money or time or effort, we will behave illogically to make sure that investment isn't wasted.

- MichaelAaron: So this phrase a diamond is forever really is unique. Linguistically. Because there is an element of surprise. It's not a diamond lasts forever and, you know, it comes to mind that there's a gap between what you expect to hear and what really comes out that helps the line stick. Think different by Apple should be think differently, but think different.

- MichaelAaron: It sticks in your mind in a way that you didn't expect it to.

- Richard: Yes. And powerfully is a representation of the point they're making and they are communicating differently. So I feel Apple probably one of the most powerful examples of this happening.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. And we have a episode coming up soon where we're going to investigate Apple further.

- Richard: You have all the brands that we talk about I think is putting Apple the most consistently use insights from psychology just again and again and again.

- Richard: They come back to various different behavioral science tactics to promote the brand.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, almost from its roots. I mean, Steve Jobs wrote a lot about how understanding consumers and understanding psychology helps them innovate authentically. And so I think, you know, it's just kind of built into the brand's DNA.

- Richard: And lots of brands talk about understanding consumers, but what they mean by that normally is just speculating about what motivates consumers.

- Richard: What's so interesting about Apple is they often use surprising insights from psychology that I think people wouldn't get to if they were just

- MichaelAaron: doing focus groups.

- Richard: Exactly.

- MichaelAaron: They were just doing regular qualitative and quantitative research. So an interesting linguistic trick kind of helps cement their line in the brains of buyers. But that's not all De Beers did to become this $80 billion a year industry.

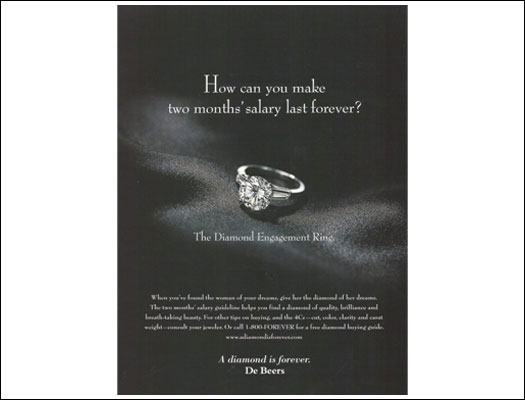

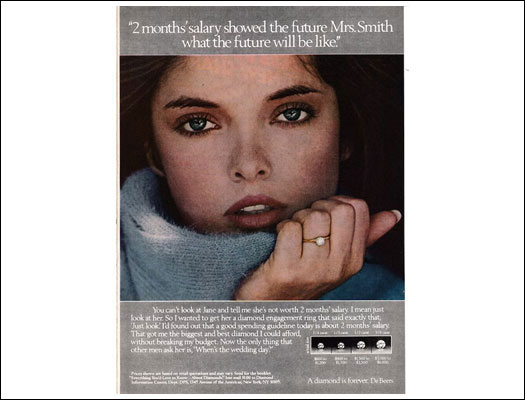

- Richard: Yeah, if that's all they had done, it would have still been a very successful market example. But even Francis Garrett, his amazing line isn't the best thing. But. De Beers That's right. I think the best thing De Beers have done is apply an idea called anchoring. So the idea of anchoring is you throw out a number, an even an irrelevant number, and that affects people's deliberations.

- Richard: So the example from De Beers would be they created a benchmark or an anchor for how much people should spend of their salary in a diamond ring. So they went out and said, you should spend

- MichaelAaron: too much. Two months

- Richard: So Britains, it was a month.

- Richard: More recently it's become two months, I think was always two months

- MichaelAaron: and always two months in America and in Japan, it's three months.

- Richard: Yes, I think they only launched in the 1980s and Japan's had been no heritage of diamond rings for engagements in Japan, so there was no expected amount to spend. And I push their luck by setting it up three months.

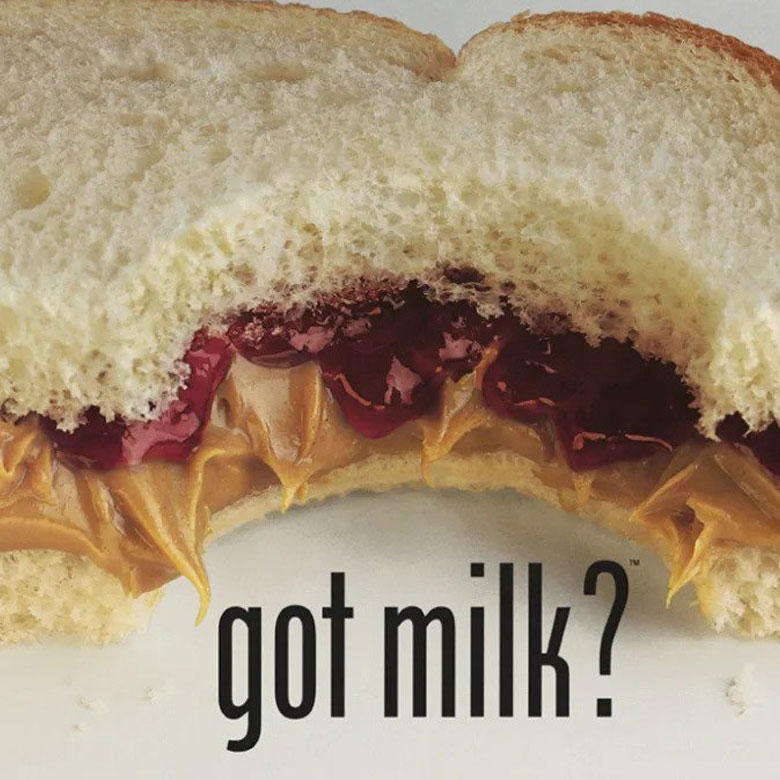

- Richard: Now, I think the Japanese spent more than any other country on their engagement rings. Now, the interesting thing here is it might feel like a very throwaway line, but there's lots of experimental evidence that suggests it's powerful. Probably the first experiment comes from Daniel Kahneman. He won the Nobel Prize back in 2002 for economics, and he ran his experiment in 1974.

- Richard: Very simple study recruits a group of people, and they come into his lab and when they come to the lab, there is a wheel of fortune. So he spins this wheel and it ends up on a number.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: Now, Kahneman and his research partner, Amos Tversky, have rigged the wheel of Fortune. So are either stocks on ten or it stops on 65.

- Richard: So roughly half off by each number. Once the number stopped, he got the participant to read out the number. And then he asked the politician to estimate what proportion of countries in the UN are from Africa and if the number has stopped at ten, the average guess is 25%. If the wheel of fortune is stopped at 65, the average guess is 45%.

- MichaelAaron: Amazing.

- Richard: Yeah, exactly. Time little tweak, very different estimates. Economists argue for why this happens. He says none of the participants know the actual answer. And so therefore, there is this gray zone of uncertainty. Now, obviously, people know it's not 100% and they know it's not 0%, but what Kahneman argues is if they have just seen the number ten, they know that number is too low, so they start adjusting upwards.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: And they stop once they hit the kind of lower bounds of that gray zone of uncertainty. So 25%. Whereas if their guess has been preceded by the number 65%, they take 65 as the starting place. Exactly. They know it's too high, so they start adjusting down. But they stop once they hit the top of that zone of reasonable numbers.

- Richard: So Kahnemann is arguing that this original anchor sets the starting place for your deliberations? You're not fixed there. You will adjust from it, but you tend not to adjust it off. It's a comeback to diamond rings. You throw out the number of one or two or three months salary. It's not that people in those countries spend exactly that amount, but an American thinks about eight weeks salary, probably thinks that's a little bit punchy and then just look down and says, well, I can't quite afford it. I'll spend five or six.

- Richard: So you don't determine the exact amount people spend, but throwing in that completely irrelevant number, you affect what people actually end up doing.

- MichaelAaron: And so I went searching, What is the real number spent in America? The jewelers of America put out a report and they said the average American spends about $4,000 on an engagement ring, on a diamond engagement ring.

- MichaelAaron: If the average US salary is just over 3000 a month or around 37,000 a year, that would mean they're spending a little over a month's salary on engagement rings. They went on to say that you've got to account for the ultra wealthy pushing up the average income. But to your point, they're spending somewhere between a month to two months salary, all given by an anchor from the DeBeers company,

- Richard: which is insane.

- Richard: Why would you listen to a salesman who has a very obvious vested interest in how much to spend?

- MichaelAaron: Right. But the principle of anchoring is just throwing out any number that people take as a starting place. They will adjust, but they don't adjust enough. And two bears have literally made billions of dollars from that very simple insight.

- MichaelAaron: And to build on that, they also understand that their consumer is in a vulnerable moment. Right. The buyer is trying to show their love for their partner and having never bought a diamond before, they have no frame of reference.

- Richard: You're actually right. I think on the point of having no frame of reference buying in a situation of uncertainty

- MichaelAaron: or buying in a situation of high emotion and uncertainty, these

- Richard: I think you're right.

- Richard: And both those elements, they probably act cumulative in the same direct.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: But there was a wonderful debate between the two economists when behavioral science first reared its head or behavior economics first reared its head. So there's an English economist called Campaign Mode. And when some of the work economists first could first come out, he was slightly dismissive.

- Richard: He said, look, all these nudges, these biases, they might work when consumers are buying bags of crisps or cans of coke, when they are trivial purchases, when people don't have a vested interest to think things through. Clearly. But he said they're not going to work when we're talking about buying diamond rings or houses or cars and

- MichaelAaron: classical economists point of view

- Richard: Yeah, exactly. Because suddenly so much money is at stake, surely people are going to think differently and rationally. But Richard Thaler, who went on to win the Nobel Prize, I think in 2018 or 2019, he said, look, can you've got this completely the wrong way round. When people are buying cans of Coke, they do it so regularly, they know their preferences when they buy diamond rings or they buy cars or they buy houses, they do it so irregularly they don't have the personal knowledge to fall back on.

- Richard: They know that they don't know. And it's in that situation, uncertainty. Some of these biases become particularly powerful. So your right, the anchor that they used, was very, very powerful, I think mainly because it was this situation of uncertainty and therefore people are more open to being steered.

- MichaelAaron: Speaking of uncertainty and a little bit of nervousness as we come to the end of the episode.

- MichaelAaron: Richard I thought it might be fun for our listeners to hear a little bit of our own engagement stories. Without asking Jane your wife or permission, will you share your engagement story with the listeners?

- Richard: So I proposed to Jane in Highgate Woods in North London, and then I think afterwards we went for a fish and chips at a local chip shop and then a bottle of champagne and fish and chips in the park.

- Richard: So a nice mix of the everyday inoffensive things.

- MichaelAaron: And was there a diamond ring involved?

- Richard: There was a diamond ring. I'd been down the day before with my brother. Two days out. There's a row of jewelers in London called Hatton Garden and loads and loads of jewelers all next to each other. So we went down there to buy the ring the day before.

- MichaelAaron: Beautiful, beautiful

- Richard: And you?

- MichaelAaron: I got engaged to Erika, my wife, 53 weeks to the day after we met, because she told me I couldn't do it until after a year at the spot where we met for our first date. And yeah, a diamond ring.

- Richard: Very nice

- MichaelAaron: from the Manhattan Diamond district. Just like you went to your diamond district. I went to mine.

- MichaelAaron: And it was everything that you would think it was. It was, you know, meant to be a symbol of my commitment.

- Richard: Yes. Yes. I think it sticks in my mind is when you go to those areas of jewelers, I can remember they give you these giant trays, like to look at the diamond. They like always take outside, you know, have a look in the line.

- Richard: You're like, you're just giving me thousands upon thousands of pounds. Sure. But you go out, you think this is weird, but someone's just giving me all this time and I could just run off with. But you look around the street and there were an awful lot of burly men with earpieces dotted along the streets, various roving security guards fastened, chatting.

- MichaelAaron: There's none of that in at least New York's Diamond district. You go behind a locked room, behind a locked room, and a lot of looking at things through microscopes, which makes you wonder, will you ever really see the difference in the grades of diamonds?

- Richard: It felt so important. The diamond

- MichaelAaron: But these are the things you learn as you go through life. So Richard, like we like to do at the end of every episode.

- MichaelAaron: We want to sum it up for our listeners. What are the big takeaways from this episode?

- Richard: Three big things. The first is a little bit of linguistic quirkiness. Can't be your friend. That if you make it slightly hard for people to understand what you're saying and they're prepared to put that effort into, there's a balance to be struck, then you make it more memorable.

- Richard: So a diamond is forever trumps a diamond lost forever. The second thing is this idea of anchoring the broad idea that when people watch the value of a product, they are not just thinking about the inherent qualities of the product as part of what they're influenced by. I have superfluous data. If you throw out a really big number before someone considers your product, you can increase their willingness to pay. The third key point for the episode is don't think behavioral science is just there for trivial purchases.

- Richard: The work from Thaler suggests very big purchases because they're infrequent. They are particularly influenced by behavioral science biases because people don't have their own experience to fall back on, and therefore they look at what the others have done or they look for some of these cues like anchoring.

- MichaelAaron: Well, thanks everybody, for tuning in today and for being with us for another episode of Behavioral Science for brands where we decode the science behind the art, I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: If you enjoyed our show today, give us a good rating. Leave a review. And if you are trying to use behavioral science with your brand or your company, let us know about it. Connect with us on social or shoot us an email at [email protected]

- AD: Behavioral Science for brands is brought to you by Function Growth AdAge’s 2023 Newcomer Agency of the year. Function Growth uses behavioral science to supercharge growth for direct to consumer brands. They operate across a wide spectrum of services as a one stop shop and integrated strategic partner for brands with high growth potential. Unlike typical agencies, function growth leverage is shared risk and reward compensation models, meaning they only make money when your brand grows, reach out to them. If you'd like to unlock the power of behavioral science to accelerate growth for your brand.

Episode Highlights

History of Diamond Engagement Rings

Diamond engagement rings were not always the norm; De Beers played a pivotal role in popularizing them globally.

A Diamond Is Forever

The famous slogan "A Diamond Is Forever" is analyzed from a behavioral science perspective. The uniqueness and slight linguistic quirkiness of the phrase make it memorable, according to a study by Daniel Oppenheimer.

Anchoring in Diamond Purchases

De Beers effectively used anchoring by suggesting that people should spend a specific portion of their salary on diamond engagement rings, influencing consumer behavior.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.