Episode Transcript

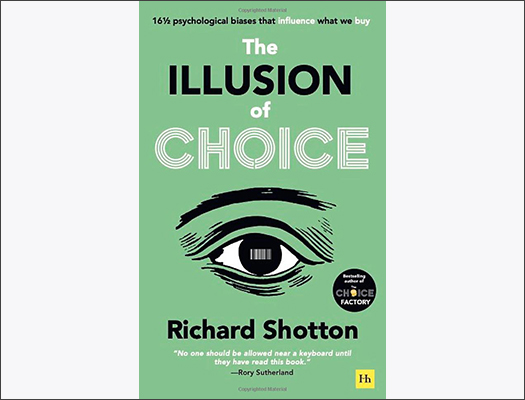

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to the Behavioral Science for Brands podcast, where Richard Shotton and I decode brands. Apply behavioral science and bridge the gaps between academic studies and practical marketing applications today. Vacuum cleaners, real estate and an unlikely invention, the ball barrow. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

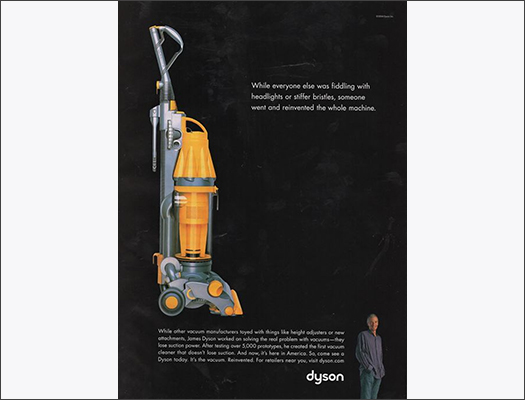

- MichaelAaron: Let's get into it as two entrepreneurs, Richard, and I have a side hobby of loving to learn the backstories behind these amazing companies that we profile here on our podcast. And of all the companies that Richard and I have chosen so far, one of the most amazing stories of a founder is James Dyson and the Dyson company. To see how he has approached making products over 50 years was inspiring to us. It was fun to learn about, and more importantly, it shows the power of the entrepreneur to bring a new product to market, even under the most unlikely of circumstances. So, Richard, let me set the stage for you and for our listeners.

- MichaelAaron: It's 1970. James Dyson is just finishing his stint in university in the United Kingdom, and he's working on his first invention, this amazing device called a ball barrow. Sounds like a wheelbarrow, but instead, it has a big ball at the front instead of a wheel. And if you see pictures, you take a look into the show notes, we'll show a picture of the ball barrow.

- MichaelAaron: It was a modified version of a wheelbarrow that uses a ball instead of a wheel to make it, uh, much more versatile. And this is first of its kind product that's meant to make gardening much easier and leverages that famous ball that we all have now seen in the Dyson vacuum today. So while his ball barrow isn't a hit right away, it's a lot of fun to look up and see.

- MichaelAaron: As he's continuing to work and think about things to invent, he gets his first vacuum cleaner. It's called a Hoover Jr. And him and like apparently everybody else in the 1970s. He gets frustrated by every time he uses it. The more he uses it, the less suction it would have. But Dyson is the first person who empties the disposable paper bag and tries to restore the suction by pulling out all the dirt and debris on the inside.

- MichaelAaron: But what he realizes is even if he removes all the debris, it still doesn't increase the suction. And that's because the fine material mesh on the inside of the bag gets clogged up, that and it can't be cleaned. So he realizes is there a way to bypass the bag altogether? Is there a way to use a cyclone to extract dust without clogging the machine.

- MichaelAaron: And if he could do it, he could do it without using a vacuum bag at all. His first version of building this vacuum cleaner is constructed in his house using cardboard sticky tape, and he connects it to his Hoover vacuum with the bag removed to see if it can work. When he shows it to others, they say, if it was possible to make a better, stronger vacuum cleaner without a bag, why wouldn't Hoover or Electrolux have already invented it.

- MichaelAaron: Undeterred, he goes into the back shed of his house, and he develops 5,127 prototypes between 1979 and 1984 to get to the vacuum cleaner that we all have known and seen today. And maybe it was less interesting to the industry because in the late 1970s, early 1980s, the vacuum bag market itself was over 500 million dollars a year in sales.

- MichaelAaron: No one was interested in licensing a vacuum cleaner that wouldn't require repeat purchase of a bag. But Dyson eventually finds a route to market, and now we have this really amazing invention that has spurred the entire Dyson line of products today. So, really inspiring story, interesting story about the founder, but in this story, there's a lot of the roots of what he will use to market the brand, and there's a lot of the roots of what makes the brand so memorable. And there's some real interesting behavioral science behind it. Where should we start, Richard? What's a good place to dive into the story?

- Richard: So I think the key thing that you mentioned there from a behavioral science perspective is the fact that he went through 5,127 prototypes. That is something Dyson emphasized in all their PR, in all their communications. And from a behavioral science perspective, it's very powerful. It taps into an idea called the illusion of effort. This is the idea that the same product will become more appealing if people can see the effort that's gone into it. That's not speculation. There is a 2005 study from Andrea Morales, at the University of Southern California. She goes out, recruits group of people who are all in market for a flat. She gives people a list of 10 flats that meet their requirements, and sometimes she says, the realtor took one hour to get this list together and they used a computer. Other times she says, the realtor took nine hours and they pulled this list together manually.

- MichaelAaron: So clearly there's a lot more effort in the latter than the former.

- Richard: Exactly. Same product though. Everyone sees exactly the same list of houses. Got it. It's just they get this story around it, sometimes emphasizing effort, sometimes not. When she then asks people to rate on a scale of zero to a hundred, the quality of the realtor.

- Richard: If people have heard the low effort story. They rate the realtor at 50 out of a hundred. If they've heard the high effort story. They rate the realtor at 68 out of a hundred, a 36% improvement in ratings based on the amount of supposed effort that went in rather than the absolute, an objective quality of the product,

- MichaelAaron: a 36% increase, not having anything to do with the results, only with the perceived effort. Yeah. Why does Morales say this happened?

- Richard: So, she says that , Maybe what we should do as people is judge the quality of a product. By its inherent characteristics, but she says, actually that's quite hard. You know, working out if a product is high quality or not involves a lot of effort. And her argument is that often when people are faced with a complex calculation, they replace that with a simpler calculation that is almost as effective.

- Richard: People prioritize ease over accuracy. And in this scenario of the realtor, the simple question is not to weigh up the brilliance or not of the properties they've found. It's to think, did they put much effort in? And people use that as a proxy question. So, her argument is, as a brand, you need to be more transparent about the efforts you go to.

- Richard: She says, most brands go to huge efforts to create a great product, but what they often fail to do is tell the audience brands labor under this mis assumption that the quality of their product will speak for itself. That's false. You need to let people see the efforts that you've gone to, you know, pull back the curtain, let people see the effort.

- MichaelAaron: So, it happens to be true that Dyson did 5,127 versions of this vacuum cleaner, and they feature it in the ads. But even if you don't have it, James Dyson as the inventor and a serial entrepreneur, you could still show effort. In your own way for your own brand?

- Richard: Absolutely. So there, there, there's lots of other different ways to apply this. Um, other psychologists who've expanded in the area, people like Buell and Norton, and they've run a couple of studies that I think are useful. Firstly, in 2017 they looked at restaurant design and they showed that if people were in a seat, in a restaurant where they could see into the. They would rate the dish 22% better than other people in the restaurant who couldn't see into the kitchen.

- Richard: Amazing. Yeah, and I think this one is interesting because everyone knows there are chefs at work. All you've done is make that work more visible, more obvious, more salient. So, it's not that, there was some amazing backstory like with Dyson. This is a much more everyday experience, but just letting people view the kitchen see the efforts going on.

- Richard: You'll appreciate the product more. The other study that I think is fascinating from them is an e-commerce one. So here it's a slightly older study, 2011, they work with a travel comparison site, get a large sample of people. Get them using the site. Sometimes people experience a really slick, seamless service, the results of their comparison are shown immediately.

- Richard: Other times on that results page, they slow down the page and they put a couple of seconds, um, delay in. While there's the delay. They have a little circular bar going around saying, searching Alitalia. Searching. Delta Airlines, searching British Airways. Now for those two groups, they question them on how happy they are with the results.

- Richard: And the group that have had the slow down experience, but also have been shown the workings behind the scene, they rate those results as 8% more comprehensive than the original group. So even in your website design, by being very, very clear about what you are doing. At any moment of delay, you will improve the customer experience.

- MichaelAaron: Man, I'm sitting here thinking about our conversation and a lot of times we say, how can we apply this for our brands in the marketplace? But this takeaway feels like there's such a big application for how we all show up as professionals to our bosses. Or how our agencies show up to the brands that they're engaged with.You may have gotten this idea in 10 seconds or 10 hours, but the illusion of effort that it took, diligence and time and energy will make it 36% more likely to be received better.

- Richard: Yes, and there is a danger, isn't there? The better you are sometimes the quicker you can be and therefore you are less likely to be using this illusion of effort.

- Richard: In fact, there is a lovely Dan Ailey, who's at Duke University. He has this lovely anecdote. He says, one night he was out gets speaking to this really old locksmith, and locksmith tells me about his career and locksmith says, saying that at first, he's quite puzzling. He says, well, when I was starting out my career when I was 16 and I was pretty awful at. My job, I would go to houses, I would fumble around the lock. I'd often damage the lock it, but it'd take, and it'd take me ages. But bizarrely, I was given these very large tips. Now I'm an expert. I've been doing this for 40 years. I turn up a house, I can whip out their lock, get a new one in, never damage the door.

- Richard: I'll do it in two or three minutes. But people are disgruntled, and I get smaller tips because what people are doing. Is falling for the illusion of effort. They are not judging him on the quality of his service that's getting better. They're judging him on how long it takes, and they are disgruntled that he's charging a reasonably large amount for a few minutes work.

- Richard: What Ailey would argue is if you are that professional with lots of experience that you can do things very quickly. What you've gotta do is reframe the conversation, move it away from, it took me a few minutes to, I'm drawing on my 40 years of experience. That's the thing you've gotta make salient.

- MichaelAaron: Oh, I think that's so, that's so important for people to hear. There's a famous in the New York City culture story of a New York City design agency, Pentagram, and one of their founders is Paula Scher. And she is in a meeting with Citigroup, which is a major US bank. And they are in the middle of a merger and she designs the new logo for Citibank, in about five minutes on the back of a napkin.

- MichaelAaron: While they're giving the briefing, she designs it and at the end of the briefing, she hands it to the client and her agency is saying, we need to spend weeks on this, months on this. This is a massive new project. And she says, I'm making up the years, this Design took me 33 years and five minutes. Yeah. So, the concept is you're paying for all of her experience, all of her time, and then the sketch that became the winning Citigroup logo.

- Richard: Yeah. So, you can go for that approach, folks on the, uh, experience. The other thing, which is slightly more Machiavellian, which is my, what my gran used to do. Is slightly different. So, my granddad was an engineer and ran a small engineering firm, but he wasn't a great necessary businessman, never made much money.

- Richard: He died quite young and my gran took over, knew nothing about engineering, but was a far better business person. What my granddaddy used to done was super good engineer, fix the cars in, you know, half an hour, ring up the client, tell them the cars there just as Ailey says they were pissed off or they had to pay this bill and they'd hardly no time.

- Richard: What she used to is get the teams to fix the cars just as quickly, and then she'd just hold onto them like for a day or a few hours and then ring the client up. So, what's interesting there is she'd never heard of Andrea Morales, but her kind of attuned ear for how customers react. Had got her to the same principle, but it took her like 50 years of experience. We can just jump in straight away to the solution because we know about Morales's experiment.

- MichaelAaron: Okay, so let's head to break. When we come back, we're going to dig deeper into the Dyson case study and we're going to share the results of another nationwide study of Americans and how we can learn from that as well.

- MichaelAaron: The Behavioral Science for Brands podcast is brought to you today by function growth. They are a team of direct-to-consumer experts and marketers who snap into brand side teams and accelerate growth. And here's the best part. Function growth leverages a shared risk and reward model. Which means they only profit when your brand profits. They have a proven track record of using behavioral science with some of the fastest growing direct-to-consumer brands in the country. To learn more, visit them at functiongrowth.co.

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to Behavioral Science for Brands. Richard Shotton and I have been going deep on Dyson and James Dyson their Founder and lead inventor. You know, Richard, one of the things you and I always talk about is, it's really interesting when you have one study, but if you can have multiple studies, it starts to give that sense that you know that this is applicable in other areas. Yeah, it's a better way of evidence. And so, you know, we have the ability to do nationwide studies pretty easily between the two of us, and so we said, let's commission another study. And it was so successful in the last episode, we thought, let's do it again here.

- Richard: Yeah. Yeah. Before the break, we discussed the Morales experiment and we saw that, for realtors, if people thought they'd gone to lots of effort, they were perceived as higher quality. That's quite a niche area, though. Most of the people listening are not gonna be working in that specific sector. Right, right. So, we wanted to see whether or not we could take this principle and reapply it elsewhere. We got some imagery for a fictitious brand. Uh, we called it Black Sheep Vodka.

- Richard: Yes, exactly. Uh, we showed people the design of the bottle, uh, 278 people in total. Half of them were just asked how good you think this design is? And 17% of them thought it was good or great. The other half were shown exactly the same picture, but they were told that it had gone through 143 iterations. They had had 142 other designs before this one. When that. Rated the quality of the design. 23% of them thought it was good or great, so there was a 35% improvement in the rating of exactly the same imagery if people thought lots of effort had gone into it.

- Richard: So yes, this works with realtors, but it also works with vodka bottles. This idea of the illusion of effort straddles multiple sectors.

- MichaelAaron: Was it 36 in the Morales experiment at 35% in ours?

- Richard: Yes. Remarkably similar. Yeah. I mean, I wouldn't, yeah, I was just say, it's just remarkable how close.

- MichaelAaron: You know, the Morales experiments at 36% lift, ours is at 35. It's just a remarkably similar numbers. And something that struck me, and we've talked about this in previous podcasts, is the exactness of the number that we used. So how many. How many versions of the Black Sheep vodka did we say we had? 143 designs. And how much, how many versions of the invention did Jane Dyson say 5,127?

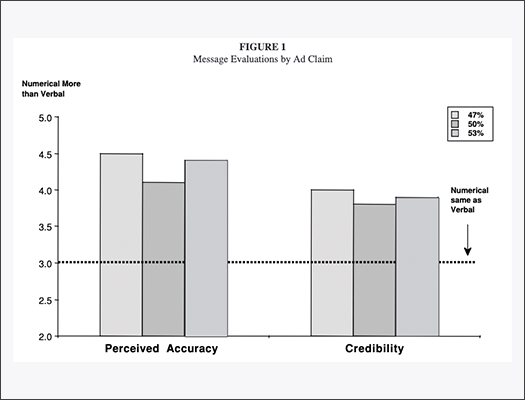

- Richard: There's something here. Oh, absolutely, absolutely. There is a lovely study from Schindler, Rutgers University, all about the power of precision. So, he gives a group of people, a made-up ad for a deodorant and within the body copy half the people hear. The deodorant reduces perspiration by 50%. The other half hear that the deodorant reduces perspiration by either 47% or 53%.

- Richard: When he asks everyone to say how accurate and credible they think the claim is of perspiration reduction, he sees a significant difference in terms of accuracy. , if people have heard the precise number, they rate it 10% higher. If they, uh, ask about credibility, the precise number is rated as 5% higher. So what he's arguing is that when we hear rounded numbers, we are suspicious.

- Richard: We think whether being made up, we associate really strongly lack of knowledge with rounded numbers. You think about your own personal experience. If someone says to you, how old is your second cousin? You'll say, oh, they're in their thirties, they're in the forties. If someone says, how old's your brother or sister, you'll say 39 or 42.

- Richard: If you don't know what you're talking about, you tend to talk in generalities. If you are sure of yourself, you tend to talk in specific exact numbers, and what Schindler argues is people learn that over of time. So when they hear a claim, you can boost the probability of being believed if you truthfully talk about the exact specific number, rather than for ease, rounding it to the nearest 10 or a hundred.

- MichaelAaron: And the application for that is you could have just as easily said, uh, Dyson James Dyson, founder of Dyson, did over 5,000 designs. and that would've got nearly be nearly as, um, likely to increase the perception of the brand than saying the exact number

- Richard: Shindler would say people would be skeptical. Uh, interestingly, I mean, what you've just described is what Dyson originally did. It was only over time that they moved towards the 5271 number. They began by saying a few thousand prototypes of 5,000 prototypes. But whether or not. They had heard of Schindler's experiment over time, they refined that messaging until it was very, very specific. And I've certainly noticed in other ads I've seen for them on social media. Uh, they've got hair straighteners, for example. Um, they talk about specific numbers in their, in their body copy. So their hair straightener, they talk about, they tested it. 422,000 times. Not nearly half million or over 400,000. Yeah, I think they have very clever and astutely applied. This principle of precision and super easy for you to do is a marketer, just as easy as using a round number.

- MichaelAaron: It may work even more for a brand that. Brand ethos is around invention and precision and, you know, and, and technology, but it can work for anyone.

- Richard: Yeah, that's, that's an interesting one. It might also perhaps convey an attention to detail. Absolutely. That's right. That's right. You know, one of those I've always thought about is, and I've got no evidence of this, but maybe it's saying we should test charities should apply precision far more. Don't ask for $10, ask a $9, 87 or $10, 13, because I think yes, you get the benefit of what Shindler discusses, but what I also think is it applies it implies that you are really looking after your every single cent, and that is something that, you know, will hopefully unlock more donations.

- MichaelAaron: So, interesting. Another thing that you and I have spent a lot of time chatting about, uh, that comes to mind right now is, The other unique thing that Dyson has done so well is change the design of the vacuum so that you can see through to the individual parts that are working. You can see the brush spinning, you can see the cyclone in the Bagless area where the, where the debris is spinning, and you can make your success evident because of the way the actual product is designed.

- Richard: Yeah. I think it's fascinating because it shows behavioral science isn't just something you use in your advertising claims. It can be brought through to product design. It's more than communication. Yeah, and potentially more powerful because any claim from an advertiser is going to be interpreted cynically actually. Creating a transparent product, well, that's the evidence of your own eyes. You're likely to give that greater credibility,

- MichaelAaron: and we want to make our successes evident because it makes that consumer moment of truth much more salient.

- Richard: Yeah, it's very similar to the, the, the Boel study now, let people see into the kitchen. They'll rate the quality it, the food, 22% better than those who can't see it. So, I think. Dyson, yes, they applied beautifully in their comms, their PR, but it goes all the way through to the product design.

- MichaelAaron: So Richard, we always love to end our podcast with the most important points we want marketers to take away.

- Richard: Yeah, this one I think is quite straightforward. It is. Do not rely on the quality of your product alone. Make sure you emphasize the efforts that have gone into it. Be far more transparent by the efforts you've gone to. What Morales argues is the same product will be rated higher if people are clear about the efforts involved in its creation.

- MichaelAaron: And communication is just one way to make your effort known.

- Richard: Very true. Product design, communication, PR, all of these disciplines are about influencing people. And behavioral science tells you the best way to influence people so it can be applied in any of those different aspects.

- MichaelAaron: So Richard, we spent the last podcast talking all about Dyson vacuums. Uh, remember your wife is listening. What is your household chore that you do at home?

- Richard: Oh, uh, I pick up after the dog in the garden. That's probably the, the

- MichaelAaron: least favorite of all the chores. Yeah, yeah, yeah. For me, in the flicker household, Erica, my wife loves to vacuum. Yeah. It's her first choice of chores to do. Yeah. Which leaves me washing dishes almost every night.

- Richard: Now , what proportion of the chores do you do.

- MichaelAaron: Oh, she'll be so happy to hear that you asked this, Richard. I made a mistake and I thought that we split the household duties. 50 50.

- Richard: Yeah. Now, on that, I have no idea. Obviously, whether you do or don't. However, there is a wonderful study that gets couples and asks them what proportion of the chores they do. So, they're asked individually.

- MichaelAaron: Uh, before you tell us this, I will let you know that I thought it was 50 50. Yeah. Okay. Erica had a very visceral reaction. Yes. She, she's clear that it was not 50 50. I would like to believe, uh, we're at a, about a 30 70 split. Okay. I would really like to believe.

- Richard: So, this study found if you ask people individually when you add up their numbers, yes. They never come to a hundred. They're always much, much higher. So 130, 140, 150% . So, you, but you have this fantastic, fascinating finding of both parties think they are doing their fair share and often overestimate that I've done and therefore get annoyed with their partner.

- Richard: Um, I reran that study amongst a pitch team at and so a small pitch team, and I asked them how much of the pitch work they've done. And people were, it was a wild number. It's about 200 or 300%. It added up to. So, I think there's something interesting here where if you're managing teams is for people not to be annoyed with those that they're working with. You've got to make it clearer about what others are doing so people don't feel they've been taken advantage of.

- MichaelAaron: Thanks so much for tuning in to the Behavioral Science For Brands podcast, I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: If you enjoyed our show today, please give us a good rating, leave a review, and if you're implementing behavioral science at your company or with your brand, let us know. Email us at [email protected].

Episode Highlights

Illusion of Effort

Consumers think better of a product when they see the work that goes in. A study from Andrea Morales tested whether consumers rewarded firms that demonstrate high-effort.

Black Sheep Vodka

To explore if the success of Morales' real estate findings could be replicated in other fields, we commissioned our own study to look into whether her findings held true for industries like vodka.

Power of Precision

Schindler argues that when we hear rounded numbers, we are suspicious. We associate really strongly lack of knowledge with rounded numbers vs. precise numbers.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.