Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to The Behavioral Science for Brands podcast. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: Today we're going to reveal the behavioral science behind some of the world's most successful brands and bridge the gap between academics and marketing. So welcome back to Behavioral Science for Brands podcast. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

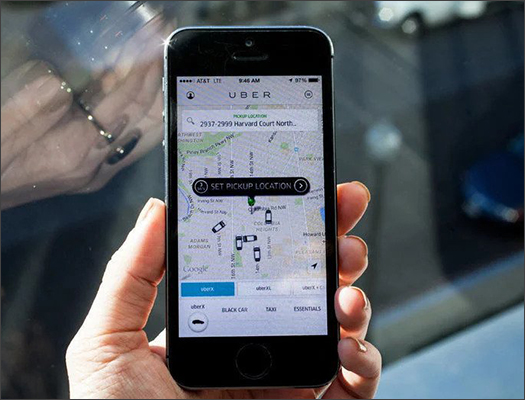

- MichaelAaron: And we are getting nerdy on all things behavioral science. Today we are going into the pain of payment, Jeff Bezos, and some basketball tickets, to really uncover how Uber has had behavioral science at the core of so much of how the brand was built from the ground up.

- MichaelAaron: But before we deep dive into behavioral science and Uber, it's always so interesting to hear the story behind the brand. So, Uber starts, not as a massive company initiative; it starts as a side hustle between two successful entrepreneurs: Travis Colonic and Garrett Camp. And these guys have both, entering Uber, just recently exited from successful ventures.

- MichaelAaron: Colonic had sold Red Swoosh to Akamai Technologies for 19 million. Camp had sold Stumble Upon to eBay for 75 million dollars. And so, they're attending Le Webb, which is an annual tech conference. And this is where they come up with this idea. What if there's a way to create a black car service at the push of a button?

- MichaelAaron: This idea quickly explodes, getting the attention of a lot of big name investors, from Menlo Ventures to Jeff Bezos to Goldman Sachs, early on, a year or two after they start their new company. Now, Uber is the leading ride sharing app available in 600 cities, spread across 65 countries, with more than 75 million users using Uber each month.

- MichaelAaron: So, in this episode, as we dive deep into Uber, we're really interested in the pain of parting with your money, opening your wallet, and how taking cash out could be a very painful experience for consumers. And so, the question that we want to ask is: how can brands make paying for a product be less painful?

- Richard: Yeah, it's a fascinating question because the standard economic point of view would be, well, you can reduce that pain of payment by reducing your price.

- MichaelAaron: Right. Make it cheaper.

- Richard: Exactly. The problem from the brand's perspective is that it will really damage your margins.

- MichaelAaron: Right.

- Richard: What behavioral scientists would suggest is before you reduce your actual cost, you should focus on reducing the psychological pain of payment. And what they mean by that is there is a repeated set of experiments which show the more distance you put between the active handing over cash and getting your product, the less painful it feels.

- Richard: So, the more recessive you make the act of payment, people will treat it as if it's a cheaper price. Now that might all sound a little bit ambiguous and abstract, but I think it will become clear if we discuss the most famous study in this area. So that was a study done back in 2001 by two psychologists at MIT, Prelec and Simester.

- Richard: Very, very simple study. They get two groups of people and they auction Boston Celtic tickets.

- MichaelAaron: Mm-hmm.

- Richard: One of these groups has to pay with cash. One of them has to pay via credit card, and what they find is that the group who pay by credit card will bid about twice as much as the group who have cash. They argue this is an example of the pain of payment.

- Richard: It feels more painful to pay with cash than it does with a credit card.

- MichaelAaron: Right, right. And for those of you that may be too young to have been transacting with merchants before, there was always the challenge of: should it be a cash payment, or should it be a credit card payment?

- MichaelAaron: So even before we get to app payments that we're talking about today, there was even the question of: can you reduce friction with a credit card?

- Richard: Yeah. And I think you're right to point out that that study was, what, 22 years ago?

- MichaelAaron: Mm-hmm.

- Richard: It's not just about paying with credit card versus cash.

- Richard: I looked at their paper a few years ago and redid the study in a very similar way, but at a shop. And we found that for contactless payments (this was about 2015 that I ran the study), you reduce the pain of payment even further than with a credit card. So, any new technology that puts that distance, adds that psychological distance, between the act of actually handing over cash, will likely reduce people's sensitivity even more.

- Richard: So, this is an ongoing opportunity for brands.

- MichaelAaron: And say you walk away from Uber and think about other industries, for example, you walk into a casino.

- Richard: Yeah.

- MichaelAaron: Right? You exchange your cash or your credit card, you swipe for chips. Is that another example of removing that sensitivity to the price?

- Richard: Absolutely. Casinos aren't stupid. They know that if they were asking people, each time they wanted to bet, to go to their wallet, take out a $20 bill and throw it on the table, that that would create an awful lot of pain of payment. By converting the dollars into plastic chips, you change how people relate to the money. They start treating it like monopoly money rather than the very valuable thing that it is. So, a casino is absolutely an example.

- MichaelAaron: And we were talking with some folks that were helping us prep for today's session and they even mentioned in America, so often casinos will give you free money in your account to start. So, you get a hundred dollars to gamble with before you have to put in your own money as another way to prime the pump to get people to not feel the pain of adding the next hundred or adding the next amount of money.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. I think there's an awful lot of psychology that goes into casinos. I mean, one of the most interesting areas is - we've talked about this before - social proof. The idea that we copy what others do. What casinos do really well is make it feel like everyone's winning.

- MichaelAaron: Mm-hmm.

- Richard: So, if you look around, you see, or you hear, the slot machines, the lights going off, and the coins clattering in the tray.

- MichaelAaron: Right.

- Richard: You see the success. Failure is invisible. So that's quite clever. You know, maybe it’s dubious morality, but it's still quite clever. It's a way of twisting people's perception of the odds of victory.

- MichaelAaron: The odds of victory. Yeah.

- Richard: Because success is obvious; failure is hidden away.

- MichaelAaron: And so, you can see Uber is really using this idea of separating themselves from the actual transacting of cash. Casinos use chips to move them away from the sense of dollars going out of your pocket. Another example that’s very common in the e-commerce businesses, is getting you on a subscription.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely.

- Richard: Once you're on a subscription, it's very easy to forget about that money coming out. You haven't got the constant reminder of going to your wallet and taking out the cash. It's a broad principle that can be applied in an awful lot of different ways.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. If you think about the thing that you found in your own credit card statements, a thing that you were getting charged for over and over again, is there something that comes to mind for you? Something that you say, “Oh my God, I didn't even think I was paying for something that I continue to pay for.”

- Richard: Oh gosh, yeah. Last time I watched a film - it was a great film, Patty Constantine was the lead in it. It was about nine months ago and I paid for a subscription. I reckon it cost about a hundred dollars to watch that single film. It was good, but it was not worth a hundred dollars.

- MichaelAaron: I desire to be at the gym a lot, so I pay my Peloton virtual subscription $12.99 every month. Some months I'll use it once, sometimes I'll use it three or four times, but I always remember thinking to myself, “the pain of it going out of my credit card is so easy.”

- MichaelAaron: You know, it's so painless. And every month then I say, “oh man, I got to use it more rather than opting in for it when I want it.”

- Richard: Yeah. And that point about opting in versus opting out is crucial. That relates to a behavioral science bias called defaults. And what people tend to do is follow the path of least resistance.

- Richard: If you have a subscription, you have to actively choose to stop it rather than actively choose to continue. It's a very small difference, but it has a large effect. There's a lovely real-world example from Britain. So back in 2013, the government changed the law. Prior to 2013, company employees had to ask to go into the pension scheme.

- Richard: So, with five minutes of admin, once you'd fill that five-minute form in, you would be getting free money from the government. Basically, they would match to degree what you were putting away. When that was the case, 61% of people in large companies were in pensions.

- Richard: They then changed the rules; so now as an employee, you had to fill in those forms to opt out of the scheme. Small bit of admin, but huge effect in the proportion of people who are enrolled. Within six months of the regulation change, it went from 61% of people being enrolled to 83%.

- Richard: Now the government in Britain are literally spending billions of pounds incentivizing people to take out pensions because they don't want the problem of lots of people in penury when they get to old age. But the thing that has had the biggest impact on British enrollment rates is this switch from opt-in to opt-out.

- Richard: The tiny, tiny change had a very dramatic effect. So as a business, you want to be thinking, how can I change the default, so that people stay with me rather than having to actively rechoose to purchase me on an ongoing basis? That's why subscriptions are so powerful.

- MichaelAaron: Absolutely. And for our American listeners - Richard and I were talking about this last night - in the British system, they would call it pensions, while in the American system, we call it 401k’s or 403B's. So for those of us listening in America, we're talking about retirement savings accounts.

- Richard: Yeah. That's the one.

- MichaelAaron: Amazing. So let's take a quick break. We'll hear from our sponsors and when we're back, we're going to dive into how this pain of payment is not the only major bias Uber has been using.

- MichaelAaron: The Behavioral Science for Brands podcast is brought to you today by Function Growth. They are a team of direct-to-consumer experts and marketers who snap into brand-side teams and accelerate growth. And here's the best part: Function Growth leverages a shared risk and reward model, which means they only profit when your brand profits. They have a proven track record of using behavioral science with some of the fastest growing direct-to-consumer brands in the country. To learn more, visit them at functiongrowth.co.

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back! We were talking during the break and wanted to know if there’s any questions that folks have, comments that you want to leave, or thoughts on future episodes. Richard and I, this is a lot of fun for us. So, visit consumerbehaviorlab.com, drop a note, reply to any of our social media posts. We're aggregating this stuff, we're already planning for season three, so just keep in touch and we'd love to hear from folks about what your questions are and what you'd like to hear us cover.

- MichaelAaron: Okay, so the pain of payment makes a lot of sense just at its face. Removing the actual pulling of money out of your wallet is one piece of psychology that we could all understand because we all touch it every day. You can feel that yourself. But Uber is really unique in that they have an entire division named Uber Labs, where they're constantly testing behavioral science principles and conducting tests, on users, even when they don't know that it's happening.

- Richard: Yeah. So, that's interesting to behavioral scientists because if you conduct an experiment in a lab and you have paid people to take part, you are introducing an element of unnaturalness. Maybe people are reacting, maybe they're acting the way that they think you as a professor want them to act. So, there's always an element of doubt that's added in with those lab experiments. What's fascinating here is, what, 75 million people use Uber?

- MichaelAaron: That's right.

- Richard: Millions upon millions of people use Uber. They don't know the prices that they are being served are often parts of experiments. So, the way they react to them is very natural. And we can give any findings from studies conducted in that naturalistic way far more credibility.

- MichaelAaron: It gives marketers a real challenge to think - as they have traffic coming to their sites, as they have segments of consumers that are buying – “how can we use the natural consumer panel that we have to learn and test?”

- Richard: Yeah. Your website is a giant laboratory. You should think about A-B testing. And I think not just A-B testing the final creative result, also A-B test the underlying psychological principle. Because the problem is: if the only tests you do are around the pictures and the colors and the expression, then you will have findings that you could only use for a month or two, until the next creative iteration comes out.

- Richard: If you test a point, like the pain of payment or social proof or the Pratfall effect, if you show on your website that the basic principle works, then that learning is valued forever. You can then pass that to your creative team and they can then spend their time thinking about, “how do we express as creatively as possible that underlying psychological principle?”

- MichaelAaron: And I would say for those listening that, Richard and I, when we consult, we often push clients and brands. We tell them: don't let anything be too sacred, even the price of your product, even the way you describe it because in an A-B test, they don't know that they're seeing a variation.

- MichaelAaron: If the variation works, then you could put more and more people against it. If the variation flops, it's a very small risk to your brand because so few people will see it.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. I think an interesting thing for behavioral science is, sometimes very strange things have a positive effect.

- MichaelAaron: Something someone wouldn't expect.

- Richard: Yeah, exactly. So, for example, sometimes if you push up the price, you can sell more because there's an assumption that the more expensive a good is, the higher quality it is. So, if your problem is a poor-quality perception, pushing up the price might be a tactic that could work. And the other thing in the field of behavioral science, is that really small changes can have a disproportionate effect. So, one of the tiniest tweaks I've seen recently was in a University of Texas Study by Peter in 2019.

- Richard: He showed that just changing the way you label products that are out of stock can have a big impact. In one of my favorite examples, he shows if you label a product as “out of stock,” you'll get far more irritation than if it's labeled “sold out,” because “out of stock” insinuates logistical ineptitude. “Sold out” insinuates-

- MichaelAaron: Consumer demand.

- Richard: Exactly. Yeah. People had such desire to buy this product. You know, it's flown off the shelves.

- MichaelAaron: So, this is very interesting. Let's dive back specifically into Uber and some of the things Uber Labs have done that we thought were really interesting for brands and marketers to hear.

- Richard: One of the previous leads on the Uber Labs team was a behavioral scientist called Keith Chen. He took part on a fascinating podcast, that we'll put the link to in the show notes, where he talked about some of the experiments that Uber have run.

- Richard: The one that I found most interesting, was when he discussed surge pricing. So, what he talked about was that if a group of customers are shown a 2x surge price, there's quite a significant drop in the proportion who will accept that ride. However, if another group of people randomly selected are shown a surge price for 2.1x, or a higher price, a larger proportion of potential riders will accept the drive.

- Richard: Now his argument is that, when people see round prices, they tend to assume they are more marked up than precise prices. That's not just based on Chen’s speculation. There are some lovely studies from the University of Florida from people like Yana Shefsky, that show this in controlled lab conditions; if people see a round price, they think it's been marked up much more than a precise price.

- Richard: So you as a brand have a great opportunity here. If you are ever selling products for $5 or $10, you could increase your margin and you can increase the portion of people who buy it, if you change the price to $5.50 or $10.11 - a rare chance to make your product feel better value and have a larger margin.

- MichaelAaron: You know, Richard, outside of Uber Labs and the studies that you spoke about, I was even taking a masterclass by Chris Voss, who's a former FBI hostage negotiator, and he talks about this same insight about the illusion of the effort it takes in a negotiation.

- MichaelAaron: So, he's applying the same behavioral science principles and he's talking about negotiation, and he says, if you get to a very specific number, it feels, because of the specificity, that it was the right number. It's the right price versus this rounded number, which feels like it was just a guess.

- Richard: Yeah. Just completely plucked out of the air and if just plucked out of the air, you're probably open to more debate negotiation. I think Chris Voss's book – it’s a brilliant book - splits the difference. Well worth a read. And it's full of practical examples.

- Richard: The other area where I've seen a practical application of the precise prices is going back to those University of Florida psychologists. They looked at house price sales in Electoral County, Florida, thousands upon thousands of sales. And they saw that if you listed your house at a round price-

- MichaelAaron: Say 500,000.

- Richard: Exactly, then you were less likely to get the asking price than people who listed their house at a precise number, say five hundred and one thousand dollars. Of all the biases that we discussed, the one that you can probably apply to the greatest financial benefit in your personal life is, if you ever sell your house, make sure you do a precise number. Now, the reason those psychologists say it has an effect on people's perception of price is that people assume all prices are marked up.

- Richard: Businesses need to put a nice little profit margin on, so everyone recognizes they're marked up, but there's a slight difference between round prices and precise prices. If someone sees a pair of sneakers that cost a hundred dollars, when they are mentally discounting that price to work out what they're actually worth, they tend to jump down in big increments.

- MichaelAaron: Like $90 or $80?

- Richard: Exactly. Whereas if those sneakers are priced at $105, they still mark it down, but they jump down in much smaller increments.

- MichaelAaron: Maybe a $101. $97, $94.

- Richard: Exactly, exactly. So, you end up with this very different perception of the worth of the products by using precision rather than the round numbers.

- MichaelAaron: Fascinating.

- Richard: It might be worth mentioning that there is one particular type of precise prices that are doubly valuable - Uber finds this as well - known as charm prices. So a charm price is any price that ends in a nine, so $9.99, or $49, or 99 cents. These are charm prices, and what Uber found is that if you drop from say, a surge price of 3x to a surge price of 2.9x, you see a jump in acceptability.

- Richard: You know, not a 3% improvement in acceptance rates, but a much, much larger jump. Why this happens is an idea called the left hand digit bias. People are operating in a very complex world. There's too much information for us to wire it all up in a fully considered manner.

- Richard:So, people think of 3x as three times the price. They think of 2.9 x as 2… something, right? So, you are jumping from 3 to 2 rather than 3 to 2.9 in people's mind. Very, very simple application. Many retailers have been doing this for hundreds of years. What's interesting is Uber's data now shows in a very realistic, naturalistic setting that even though this has been going on forever, it still has a large impact on how people spend their money.

- MichaelAaron: So, Richard, thanks so much for chatting about Uber and all the ways they use behavioral science. As we like to end every episode, let's give our listeners the most important things they should take away from this podcast.

- Richard: The most important thing is consumers do not act completely rationally when it comes to prices. You can make the same price appear more palatable by making it precise: $11, not 10, or by using charm pricing: $9.99, not 10, and finally trying to put more psychological distance. This is the idea of pain of payment between the act of handing over cash and getting your products. If you apply those ideas, you will boost the appeal of your product and reduce price sensitivity.

- MichaelAaron: Amazing. Excellent. So, the big question is, Richard Shotton at home in London, England, do you use Uber, Lyft, or some other service?

- Richard: So, we don't have Lyft. So, either Uber or you can get a taxi. But actually what I really like - I don’t know if you have quite so many in America -the electric bikes, there's loads of companies, where you just leave the bikes on the street, anywhere on the street. You just stop it and then you can, tap-of-your-card, hire it, and cycle around. And I do still find those quite exciting. That's a favorite way getting around it.

- MichaelAaron: Very exciting, very exciting

- MichaelAaron: Here in New York, there's always more options than less. An interesting new company that's starting up is called Revel. They're all electric vehicles. In fact, they're Teslas where the front passenger seat is turned around and it faces the back just like your Taxi cabs in London. It's super cool. Super cool.

- MichaelAaron: Thanks for tuning in to the Behavioral Science for Brands podcast. If you enjoyed our show today, please give a good rating. Please leave a review. Until next time. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

Episode Highlights

Uber, Chips, & Subscriptions

The concept of separating the act of payment from the physical exchange of cash is being utilized by Uber, as well as by casinos using chips to detach customers from the sense of dollars being spent, and in e-commerce businesses that often use subscription models.

Price Surging

Keith Chen from the Uber Labs team argues that customers are more likely to accept a ride with a precise surge price than one with a round surge price.

Charm Price

Charm prices end in a nine, a simple application that has been used by retailers for centuries and still has a significant impact on consumer spending.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.