00:00 / 48:10

Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to Behavioral Science for Brands, a podcast where we go deep connecting academics and practical marketing. Every other week, Richard and I sit down and look at behavioral science and see how it connects to some of America's leading brands. Today, we are very excited to welcome Kate Waters to our show, and we're going to talk much about her career, her past, and much more about her thoughts on behavioral science.

- MichaelAaron I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: Let's get into it. Kate, welcome to Behavioral Science for Brands. We're very excited to have you.

- Kate Waters: I'm very excited to be here.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. Thank you. Thank you. So like we like to do, I'm going to give a little introduction to our listeners about you and a little bit about your career.

- MichaelAaron: You build and add as you see fit. But you started your career working at EURO RSCG and a number of other agencies. You founded Now Advertising. And more recently, you were the director of client strategy and planning at ITV, Britain's largest terrestrial broadcaster. Is that correct?

- Kate Waters: Uh, largest, I guess, commercial broadcaster.

- MichaelAaron: Commercial broadcaster. For our American listeners, can you give a little description of the difference between those two things?

- Kate Waters: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Sure. So in the UK, probably - well, definitely - the largest broadcaster is the BBC, but the BBC is a broadcaster that is funded through a license fee.

- Kate Waters: So it's paid through essentially a form of tax, whereas ITV is a commercial broadcaster. So we fund our programming through advertising. So I work in the commercial team, so I'm basically in the ad sales business now.

- MichaelAaron: Got it. Got it. Got it. So you were on the agency side. Yeah. Now you're on the ad sales side. It must give you quite a broad perspective of the industry.

- Kate Waters: Yeah. It's, it's fascinating. And actually the thing that's really amazing, if you come from an agency background, you become very used to working on a few brands and going very deep on them for a long time. Um, I work in a team now where, you know, we have 2000 customers basically.

- Kate Waters: And, and, uh, you know, you work on things on a very fast turnaround basis. So it could be, I dunno, Unilever one week, P&G the next week, JustEats, you know, all sorts of brands. And I think, in fact, I've just done the numbers for this year. So I think this year my team have worked on a thousand client projects and with over 300 brands.

- MichaelAaron: My goodness.

- Kate Waters: It's so huge. It's a completely different sort of thing to manage and navigate.

- MichaelAaron: And, and would you say that, um, your, your interest is different because when you go deep with a few, you're doing, you're really working on business issues. When you’re at ITV you're helping introduce them to all of the UK. I mean, it's a totally different game.

- Kate Waters: It's completely different. And I think in my role, ITV is really different from what it was in an agency. And what I love about it is, I was the first director of client strategy there, and what that means is my job is to work with all of our advertisers to help them really make best use of TV advertising and all of its different forms.

- Kate Waters: And so that means I get to work with some of the biggest and try to persuade them that it's still a fantastic place to advertise. And actually it is, it is the most effective advertising medium. Um, and then similarly to, to introduce some of the smaller kind of scale up businesses to TV and hold their hands through that process.

- Kate Waters: So it's a really interesting job and it means that I get to work on everything from, I guess, kind of creative strategy right up front through to I have a measurement team who are basically inventing new ways to measure advertising effectiveness, which is enormously good fun.

- MichaelAaron: How exciting.

- Kate Waters: Yeah. It's a very, very big toy box with loads of fantastic things to play with. It's great.

- MichaelAaron: What a great spot to be. What a great spot to be. So today we're talking behavioral science. We're talking - But not just the academics. We're really interested in how does it get applied to brands? How does it apply to marketers?

- MichaelAaron: And how can we, you know, help bring to our listeners the power of this subject? So you've been in and around behavioral science for quite some time. We'd like to ask all our guests, where did you first hear about behavioral science? What was your first deep engagement with it? Like, how did you get started in this field in this discipline?

- Kate Waters: So actually I suppose the, literally, the first time I was introduced to behavioral science was at university because I did a, I did a psychology degree, so I did a degree which I think was called Human Information Processing, that was one of the modules, and it was basically about how people make decisions, and I absolutely hated it, and I was really, really, really bored by And I can remember doing my degree, getting it, and putting all of my notes in the attic at my parents house, as I think probably many people do, and just thinking, right, that's done, now I'm going to get a job.

- Kate Waters: And then, when I was at, I was actually an agency called Partners BDDH, which subsequently became Euro RSCG. And we got this amazing phone call. We got a phone call from, the British Heart Foundation, who are the biggest, um, I guess, uh, heart disease research charity in the UK. And they said, we've just had a phone call from what was then the Department of Health.

- Kate Waters: They think we need to work harder to persuade people to stop smoking. And they think that actually the NHS is too nice and caring and sharing a brand, uh, to do that. But actually they think that, that we could do it. So they've given us some money. You're our agency. You've got a week, see what you can come up with.

- MichaelAaron: Classic agency assignment.

- Kate Waters: It was an unbelievable brief. And, um, and so basically my job was, I mean, literally, and that's what, so the other thing they said is they said, the only thing they want us to do is shock and awe. They said the brief is shock and awe with the British Heart Foundation. So it's sort of needs, you need to make sense of the fact that we are authoring this ad.

- Kate Waters: Um, off you go. And it was literally at that point, I thought, Okay, I have a - I seem to remember that I did a bit of psychology and I think this is probably something where that might come in useful. So I literally went back to my parents house and got my notes out. Really? Yeah. And I started reading and I also was lucky that I had a bunch of friends who are medics and I rang, um, I rang my friend Sarah and said, uh, do you know anything about smoking?

- Kate Waters: And she said, no, I don't, but I live with a pathologist. Why don't you talk to her? So literally over the space of a weekend, I reread my notes and I've done a load of stuff about, um, basically, um, behaviorism. So Pavlov's dogs. Um, and then I rang this pathologist and she said, do you want to come and have a look at the pathology museum at the World Free Hospital?

- Kate Waters: So then she gave me a tour of this museum, um, where they had the pickled remains of like smokers who died.

- Richard: Wow. I'm going to take my daughter there I think.

- Kate Waters: Yeah, sadly I think it's now closed. But she saved me. So she said, this is what, this is what people's arteries look like. Um, when you, when you, after you've essentially died, um, and this effect, which was, you know, when it like, it's just - all I can say is it is absolutely disgusting as it looks like a pizza.

- Kate Waters: But it's the inside of your arteries and you have no idea that this stuff is happening. So I had this like visceral image in my head of what all of this horrible stuff looked like. And then I had this kind of thing in the back of my mind, which was, um, I know that obviously the world has moved on a lot from sort of Pavlov and his dogs, but he had this idea of obviously the kind of conditioned response.

- Kate Waters: And so I was thinking, I wonder if we can create a conditioned response between somebody smoking. And then, and somehow showing them this thing, which is invisible to everybody, which is that this is what happens to your arteries if you're smoking. So we put these, these two things together and we made an ad, which is called fatty cigarette.

- Kate Waters: And it's, um, probably remains the thing of which I am most proud. Um, and cause it, it just, it's a. It got written up in the New Scientist, which in my geeky way was like, I'm proud of you. Um, but that was the point at which suddenly I put these two worlds together and I suddenly thought I'm working in advertising and I cannot believe that I've forgotten that I've got a degree in this stuff.

- Kate Waters: And actually, suddenly that makes it really interesting. So it stopped being horrible, dry academic stuff. And it starts to become a toolbox of tricks that I could apply to. you know, lots and lots of the problems that I was working on.

- MichaelAaron: There is a reframing, insight somewhere in here.

- Richard: I think there's a theme of people we've talked to who've, who've developed an interest in behavioural science of a, a kind of flash of inspiration that the world of psychology and this academic discipline could, could have a link with the business of changing behavior in a commercial sense. When you say it out loud, it sounds like something that everyone should recognize straight away, but that isn't the case. Why do you think these two worlds that could teach you so much, why are they so separate? Why so disparate?

- Kate Waters: Well, I'm sure there are a lot of reasons, but one of my observations is that advertising is full of really smart people who've done liberal arts degrees and actually there are relatively few people who have done science degrees and these days psychology is very much treated as a as a science, you know, so And I and I mean, you know, I'm sure there are lots of psychologists somewhere in advertising, but I always felt like a little bit of a loner because I had a slightly more scientific degree, you know, I did maths biology you know chemistry A levels and those sorts of things and so I wasn't afraid of science, and I wasn't afraid of reading scientific, sort of, journals.

- Kate Waters: And so I wonder if maybe it's just that the two worlds are so different. You've got a bunch of people who, in many, many cases, have got, if they've got a degree, they've got a history degree or an English degree, and this is just a world that they've just never come across.

- Richard: So although they are very similar in terms of goal, changing behaviour, The way that those things are expressed are completely at odds.

- Richard: So that's fascinating. I never thought of it that way.

- Kate Waters: Yeah, I don't, I mean, it's, it's just, I mean, that is absolutely arguing from a position of like one person, just that my experience of what the industry is like.

- MichaelAaron: But that's what we want to hear. So that sounds great. Um, before I forget, we'll ask if you're able to share it for the fatty cigarette ad and we'll put it in the show notes so that everybody can take a peek at it and learn from it.

- Kate Waters: It's very dated. I should say that it's from the days when you could smoke in a pub.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, in America it was till way too recently that you could also do it in an elevator or you know the times are changing. All for the better. All very fast. So Kate, uh, maybe what we'll do is we'll hand it over to Richard. And what we'd love to do is learn a little bit from you about where you think this has gone well, but Rich, I'll let you take it away.

- Richard: So I think you've come prepared with three different examples of brands you think are great examples of the practical application of behavioral science. So do you want to start us off with one of those?

- Kate Waters: Uh, yes. Okay, so let's, maybe we start with what I think is probably the oldest and probably the simplest in some respects.

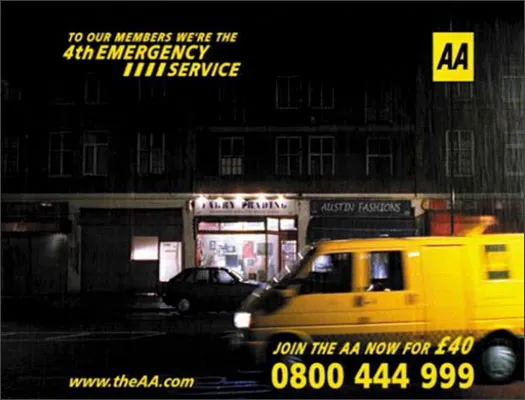

- Kate Waters: And that's the AA, which is a business which, well, so the AA, I think it probably still stands for the Automobile Association. Not—

- Richard: Alcoholics Anonymous. Not Alcoholics Anonymous.

- MichaelAaron: Ah, okay. That's what I thought we were talking about. I’m glad you defined it early.

- Kate Waters: Oh my goodness. That would have been really weird.

- Kate Waters: Uh, so no, so the AA is, uh, essentially roadside recovery. So they're, they're, they're, um, and the business has moved on, but in the example that I wanted to start with is when the business was a roadside recovery business. So essentially if you break down and they come and pick you up, um, and, uh, you know, and they, they…

- Kate Waters: Purely that for many, many years. And actually, I should have checked what year it was. It was a, it was a good, what do you reckon, mid nineties maybe? Probably, yes, a good, good long while ago. Um, they basically reframed the business not as roadside recovery, Um, but rather brilliantly as the fourth emergency service.

- Kate Waters: Um, so, you know, we have the ambulance service, the fire service, the police service. Um, and the story goes, and I think it's probably apocryphal, that they were doing a, bunch of focus groups and talking about a new ad campaign and out of the mouth of a consumer that you know this woman said, you know what I don't really think of them as being roadside recovery.

- Kate Waters: I think of them as the fourth emergency service and somebody behind the mirror thought that was you know, um, and, and took that and ran with it. And of course I think it is a phenomenal example of, of reframing a business. And it also plays to the, you know, that core truth of all behavioral science, I think, which is that, you know, when you make a decision, when you think about something, it is always a relative and comparative sort of judgment.

- Kate Waters: So it's what, what's your comparison set? So when they took that thought, It didn't just become a really powerful end line, but actually it really did transform the business. So, you know, there are lots of lovely stories about, um, the motivation levels of their, of their staff kind of like, right, you know, you just go, yeah, actually, that's really important.

- Kate Waters: I'm like a policeman. I'm like a, like an ambulance driver. That's a much more important thing to be. Um, and they even took the, um, the kind of visual language of the emergency services. So if you know, you know, the sort of checkerboard pattern that you have on the back of ambulances and things like that, and they painted it on the back of all of the roadside, you know, all of their rescue vehicles, essentially.

- Richard: Oh, fantastic. I love that as an example. The, so I think, as you mentioned, on one hand, it's changing the comparison set. The other experiment I was thinking of when you mentioned that was, there's this brilliant study involving cars, 1974 by Loftus and Palmer, and they recruit a group of people, and they play them a short video clip, and it's of a car crashing into another car.

- Richard: They say to, Viewers of this clip, how fast do you think the cars are going when they collided together? And the average guess is 31 miles an hour. Next group of people, they showed them exactly the same footage, but this time they changed the question very, very slightly. How fast do you think the cars are going when they, they smash together?

- Richard: And you see a leap of 27%. Now the average guess is 40 miles an hour. And their argument was, we don't interpret events neutrally, we interpret them through a. lens of the language that we use. So changing collided to smashed actually changes how we interpret the video footage. The psychologists were interested in witness testimony and they wanted to show that you should be very careful about what witnesses remember because a skilled policeman could manipulate them to think certain things.

- Richard: But, from our perspective, thinking about it commercially, AA seems an amazing example of that. You, you change the language that's used to describe a product and it goes from a slightly mundane service to something that is life saving and should be put on a pedestal. So I love it as an example of, you know, the power of words to define how we think of an object.

- Kate Waters: I don't know the answer to this, but what would be brilliant would be to know if it enabled them to essentially elevate their pricing as well. Cause you imagine once you've established in people's minds. Yeah. We're not a roadside recovery service. We're an emergency service. You go, “I’m going to pay a premium for that.”

- Richard: Or more negatively from the employee's perspective, reducing wages. If you become a more an admirable service, you know, you get more people demanding to be employed to pay them less. So there's flip sides there.

- MichaelAaron: I wonder how, um, you know, how you can think about using a single, a single word like you talked about Richard or a single concept can change the entire organization.

- MichaelAaron: You know, it, it's an interesting, um, it's an interesting question of, really, what do you choose as your stimulus, which was really where you started out? What are you comparing yourself to? Um, have you seen, uh, other examples of that, where you change the stimulus and it creates a different, um, and it creates a different, you know, uh, control that you're then talking about?

- Kate Waters: So I think, um, I think when you were saying that I was thinking I was going to happen as I'm going to go I have no idea and then about half an hour after. I have, I think it's one of the questions actually that I always, um, start with where whenever I'm thinking about a brief, which is what business are we in?

- Kate Waters: And is there a way of answering that question in a different way? And if you, if you do, do you get to a different answer? So, um, I think there's a really interesting example. I'm not sure if it ever actually came to fruition, but there is a, I remember sort of talking to the planner on the business about it.

- Kate Waters: So there's a business over here called Travel Lodge, which is essentially a chain of budget hotels.

- MichaelAaron: Yes. In America too.

- Kate Waters: Yeah. And they - at the time that we were kind of working on the brief, um, they were very much thinking about themselves as being in the kind of budget travel, sort of, you know, budget hotels at market.

- Kate Waters: And my boss, shout out to Malcolm White, looked at all the tracking data. And of course, if you look at all of the data and you look at the questions about how do you, why do people stay here? Most of the answers were, you know, because I'm going to a business meeting or because I'm visiting friends and family or because we're having a day out and we don't want to travel back home.

- Kate Waters: And so he said, what, what, what would, wouldn't it be interesting if, if instead of framing this as a one star budget hotel, you frame it as a five star stopover. So it's like got everything you need and nothing you don't. So it's got amazing, you know, You know, like high quality pillows, you know, fantastic, high quality mattresses.

- Kate Waters: So you get a fantastically good night's sleep, you know, but do away with the naff chocolate on the pillow. Cause nobody needs that in a five star stopover. And I don't think they went with it, but I do, you can see elements of how that has moved, you know, so actually I think, um, their competitor arguably over here, Premier Inn, I think I've gone with heavy on that, you know, you get an amazing night's sleep because that's what you want in a, in a five star stopover, not necessarily all of this sort of bells and whistles of a hotel.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, that's a fabulous second example of how you can see it that way. It's so helpful. Yes.

- Richard: You mentioned with AA that it motivates staff as much as potential shoppers. That got me thinking around reframing and there's an example, I think it might be in the Isaacson autobiography around Steve Jobs, when one of the heads of some various technical department had reduced the speed of say booting up to a ridiculously fast amount of time and Jobs told me he wanted it to be cut back again, and the guy was apoplectic at this ridiculous command.

- Richard: And then Job said something along the lines of, Well, look, you know, we have 10 million users. If you save the three seconds for each one of them, it'll add up to, you know, five lives worth of time that you've saved. And he reframed the problem as being something that was just an administrative It's like the, you know, superficial errand, so being this is, you know, you've elevated to being a, you're on par with the surgeon or, uh, any other lifesaver.

- Richard: So I think that idea of reframing is such a powerful thing if people take the time to consider it as an option.

- Kate Waters: I just think it's a trick that I think a lot of good ad agencies use, perhaps they don't look at it through this lens of behavioral science, but I think it's enormously powerful. And as I say, it's my go to question pretty much for every brief, which is which, what business are we in?

- Kate Waters: What about if we define the business as being, you know, not, I've been talking about this in the context of TV, actually, not we sell you white eyeballs, but actually we sell you business outcomes. Now, what does that do? How does that change the way in which we sell? So I think it's, it's a super useful question.

- Kate Waters: Um, A really good one.

- Richard: So that was fantastic. So that was the AA and the fourth emergency service. Did you have a second brand that you were particularly interested in?

- Kate Waters: I do. So I, so I think, um, let's, let's go with the slightly more public sectory ones, since that's where my, um, I guess my, my career is sort of, you know, in this world took off.

- Kate Waters: So, um, so I'm going to talk about Zoe. Okay. Which, is really, I think it's probably important to understand the product. So it's essentially on one level, just a diet app. So, you know, there are loads of them. You know, it's one of those where you sort of track what you're doing and, you know, you put in what your goal is and it tries to tell you how to, you know, it gives you a little nudges along the way to, um, weight and so on.

- Kate Waters: But I think what's so interesting about Zoe is that it started life as a citizen science project. So its founder is an academic called Dr. Tim Spector. He is in fact the professor of genetic epidemiology at King's in London. During, COVID, he pivoted his kind of interest, which was in sort of gastroenterology, into, into basically COVID symptoms tracking.

- Kate Waters: So he built this kind of COVID symptoms tracker, which is called Zoe, where people around the world could log their symptoms of COVID. And, uh, I think he got sort of four and a half million users or something, it was quite extraordinary. So it just took off and it became this enormous citizen science project.

- Kate Waters: And then post COVID. He's pivoted back to his interest, which is kind of gut health. And essentially use the brand, which was, you know, off the back of this kind of citizen science sort of gig, um, and repositioned it as essentially this, this, you know, diet or kind of health app. But what's so interesting about it is that when you, when you sign up to it, it's really expensive, right?

- Kate Waters: So, you know, these things, you can get them for sort of 5. 99 a month type sort of, you know, subscriptions. Now this is 25 quid a month. Plus a fairly chunky upfront cost for all of the sort of little testing that you do. So you get a kind of blood sugar monitor, you know, you basically eat a bunch of strange foods and then they monitor what happens to your blood sugar.

- Kate Waters: You do a poop sample so they can find out how your gut biome is, all this sort of stuff. And so when you get it, it presents as the most beautiful premium lifestyle brand. So the packaging is immaculate. It's absolutely gorgeous. You know, the app is beautifully designed. It's really slick. The UX is gorgeous.

- Kate Waters: Um, and, and yet it's underpinned by, I guess, what you would, you would call the sort of, you know, the, the kind of authority, um, you know, principle of, you know, actually, I believe it all because Dr. Tim Spector is behind it and his team of, you know, scientists are there.

- Richard: But that, that, that, that's fascinating because so many.

- Richard: Things that we want to encourage, you know, whether it's public health or better finances, they take a slightly puritanical approach and it's always about this is good for you, it's morally virtuous. I love the idea, as you mentioned Zoe, of bringing some of the same tactics that an Apple or a fashion brand or a luxury brand would do to make you want to engage in these behaviours.

- Kate Waters: Yeah, and I think it's, so it's gorgeous on that respect. So I suppose, again, if you sort of think about the basic principles of the EAST framework, it is supremely attractive. Yeah. In a quite literal sense. Um, but what I really love about it is this fact that you can sort of kid yourself that actually I'm justifying the expense of doing this because I'm taking part in a really proportionate and valuable citizen science experiment.

- Kate Waters: Yeah. So my data is now going into this pool of presumably hundreds of thousands of people, which is enabling the good people at King's, and it's, you know, Stanford and Harvard and Massachusetts, you know, you know, so hospitals to understand what is going on with our gut health. So it's, it's just so clever in the way it just taps into so many different motivations.

- Kate Waters: And I guess, you know, biases and then, you know, the app is, is just brilliant, you know, so it's chunking, you know, there's lots of commitment stuff. You probably, are you telling me Kate that you're going to do this thing today? You know, it's just every single layer of it is just beautifully designed, really clever,

- MichaelAaron: Fascinating.

- MichaelAaron: And so, um, Which of the of the behavioral science insights do you think they're activating against most? You talked about the EASE framework, you think it's the beauty and the simplicity of the app that's really the most?

- Kate Waters: I, I would say it's, I would say it's actually the… I guess the kind of messenger effect, the kind of authoritative messenger, I think.

- All: Yes. But

- Kate Waters: It's a combination of that and the attractiveness thing, and that's, that's why it's such a powerful combination, because I think you can sort of go, if you're using it as a diet app, then it is brilliantly credible because it's based on science. You know, so I absolutely believe these people, these people are not, you know, cowboys.

- Kate Waters: It's not all snake oil, you know, you know, because they all come with, you know, it's, you know, it's five extraordinary universities, you know, they are, they are properly good scientists. So I think there's an authority messenger. Um, you know, it's not what I would expect a citizen science project to look at like, it doesn't have the visual language of universities and academia.

- Kate Waters: It's somehow got the visual language of, of the best luxury consumer lifestyle brand coupled with an extraordinary sort of messaging around the sort of authority stuff.

- MichaelAaron: So helpful. Yeah.

- Kate Waters: Really clever.

- MichaelAaron: So cool. Yeah. I, I also wonder if there's some, something about, um, it changed, you know, being unexpected creates, like you're comparing it to now something completely different.

- MichaelAaron: So you get the authority of the universities, but then you no longer see it as a science project. You see it as a product that will must be able to help me, you know?

- Kate Waters: Yeah.

- MichaelAaron: You also talked about how it uses your name. It seems incredibly personal.

- Kate Waters: It is. So the personal is, and actually that's another, really important part of the pitch, so, you know, the whole positioning of it is, you know, diets that are made for everybody help nobody, because everybody is different.

- Kate Waters: So, so the whole principle of it is you will get personalized advice and you are different from everybody else. Now, there's probably a clever bias, I don't know what that's called.

- Richard: There are certainly arguments by things like the cocktail party effect that most information we screen out and if something is personally irrelevant we're much more likely to notice it so there's certainly an angle there potentially.

- Kate Waters: Yeah, um, but no, it's it's, again, I have no idea ultimately, I was reading some stuff online about it and there's a fair amount of, um, I'm not sure it's quite everything that it says it is or claims it is, maybe it's not quite as effective as people think it is, but I bet there's a hefty dose also of, you know, of really just, you know, confirmation bias and, you know, probably a bit of placebo effect thrown into it because you absolutely want this thing to work because it feels so good and it feels so compelling.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, I was thinking about a placebo effect when you were talking and I was does it. Yes, it matters. But if it gets you to the goals that you have set out.

- Kate Waters: Does it matter?

- MichaelAaron: That's,

- Kate Waters: yeah.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Kate Waters: I think there's one other thing about it, which I thought was really clever. So when they give you the little, they give you the thing that, um, people who are diabetic have.

- Kate Waters: Yes. In fact, I'm wearing it at the moment because I'm doing it. Um, And they fall off. So the solution to them falling off is to put a whopping great plaster on top of them, which of course would be really unattractive. Except for the fact that what they've done, so the Zoe branding is bright yellow, so wonderful, optimistic, sunny, kind of bright yellow color.

- Kate Waters: Um, and they give you this thing that literally looks like a sun, which is bright yellow, which is essentially a plaster to stick over the top of the thing to stop it falling off, which says Zoe across the middle. And of course you go to, as I did last week, go to a yoga class Transcribed And there's at least three people in the class proudly demonstrating this thing.

- Kate Waters: So they've turned something which most people would go, Oh, I've got this ugly thing on my arm. I better cover it up into a proud badge of membership. And I think that is one of the really clever things. So

- Richard: yeah, there's one of the books I really like and that had a kind of formative uses was a contagious by Jonah Berger.

- Richard: And in one of the sections, he talks about this principle of turning the private public. So if you think if a public health authority had released those, um, that's an absolute bit of tech, it'd have been grey or white, and therefore not very noticeable or not unique. By branding it bright yellow, people will notice it, it'll feel like this is a hugely popular behavior, and that starts tapping into social proof, which is one of the most.

- Richard: powerful bias there is. If we think something's popular, we at least ask ourselves, would it be worthwhile for ourselves to adopt?

- Kate Waters: Yeah. And of course, if you think about ultimately what's at the heart of this and whenever you could go, so I'm proudly advertising the fact that, you know, I might have a pre diabetic condition, you know, maybe I'm worried about my gut health and I've got some form of IBS, you know, you're basically saying you might have a whole bunch of medical problems, which is generally things people don't want to share.

- All: Right.

- Kate Waters: And yet they've turned it into something that I'm really proud of. You know, and it's, you know, like the yoga teacher came after me and says, just be very careful when you're doing Crow. We’ve had people who've knocked them off by mistake, you know, like, so it's just, you know, even that sort of, you know, stuff is, I thought it was fascinating, really, really clever.

- MichaelAaron: Very cool. And before the show you shared, you think they're going to launch in America soon. Most of our listeners are in the US right now.

- Kate Waters: Yeah.

- MichaelAaron: And so you think that this is a product that will be coming?

- Kate Waters: So I was, as I say, I was reading about it and it sort of said they are scaling up and they're looking to launch in the US.

- MichaelAaron: Very cool.

- Kate Waters: So yeah. Yeah. So look out for it. It'll be coming to you.

- MichaelAaron: Very cool. Very cool.

- Kate Waters: With it’s hefty premium attached.

- MichaelAaron: Well, this is wonderful. Let's go to a break. And when we come back, we have another brand we're going to talk more about and see where the conversation takes us. Thanks so much.

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to behavioral science for brands. Today we have Kate Waters on and Kate's talking to us about her career, about behavioral science. Kate, it's been super interesting so far. Why don't we jump into the next brand that you have and talk a little bit more about what you've prepared next.

- Kate Waters: Okay, so my third brand is Spotify.

- Kate Waters: And I suppose actually on one level, one could have chosen pretty much any of the platforms in some respect, but I think, um, I dunno - I like Spotify, sure. And I think particularly Spotify Wrapped is kind of really interesting. So I guess on one level, the most obvious thing about Spotify is the sort of social influence.

- Kate Waters: It's a fact, isn't it? So X million people are listening to this, you know, this playlist has been followed by however many people, you know, all of, all of this song has been played X number of times.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, exactly.

- Kate Waters: And actually one of the things I've always wondered is at what point, is there a tipping point where suddenly something goes?

- Kate Waters: What would it be? I bet Spotify know the answer and I wonder if it's different for different types of genre or of music or something. But there must be a point at which suddenly it just starts spiraling and it goes and goes and goes. I'd love to know what that is. That's so interesting. The literature,

- Richard: I've not seen anything from the literature.

- Richard: Oh. I think there are some very abstract gains where there's a talk of, you know, if you can persuade people that a quarter of a. You know, a sample of a doctor of behavior, then you start to get this, this tipping point. But I think those studies are at that end of behavioral science or psychology studies where they're so abstract and so otherworldly, I would treat them with a, um, a real pinch of salt.

- Richard: The other one though, it reminds me of is there was a brilliant book from 2017 called Hitmakers by Derek Thompson. Absolutely amazing. And he talks about, um, Rock Around the Clock.

- Kate Waters: Yeah.

- Richard: And how it had actually, it became one of the best selling, um, rock pop songs of the, the 1950s. But interestingly, it launched and sold like 5, 000 copies.

- Richard: Wow. Almost kind of died out, but a couple of months later, through a series of random events, the film company decided to have it as the opening music for Blackboard Jungle. And that boost of, kind of, popularity. popularity was enough then to set its way to becoming one of the biggest ever, ever selling singles.

- Richard: So he talks about that being as a real world version of people and the success of products, not just being a reflection of their inherent attributes. It's also this element of chance. And if you get, as you say, this, um, random impact that, you know, Increases, some people listening to it, that can become, that can become self fulfilling.

- Kate Waters: Yeah, no, I'm, I'm, I'm sure it does. And I guess, you know, Spotify, I'm sure will, will know the answer. I suspect like most platform digital first brands, the entire business will be fueled by experimentation and they may not refer to that as, as behavioral insight, but fundamentally that's what it is, isn't it?

- Kate Waters: It's iterative, it's constantly learning. It's kind of figuring out which version of the UX works best, all those sorts of things. But I think, I mean, there's, there's just, since. Sense of thinking about this. When I was sort looking at it, there was a few things that really struck me. You know, the, the first thing which is really obvious is it is in the, is in the menu at the top.

- Kate Waters: The wrapped bit is just highlighted in a rather you, again, and kind, just beautiful set of colors. You go, oh, I'll go there then. Yeah. You know, so it's a kind of classic, just, you know, make it salient to try, you know, draw your attention to this, you know, to this little button. Um, and then, you know, I, I, I was also thinking, and, and.

- Kate Waters: Keep me honest on this, cause I don't know if this is the right way to interpret it. But when you look at, when you open it, the kind of list that it creates, they are essentially creating a new set of defaults. Um, you know, so I guess one of the, one of the things I always particularly sort of struggle with kind of with, with services like Spotify is there is so much, where do you start?

- Kate Waters: Well, actually that kind of clever curation of playlists is essentially a set of defaults, isn't it? It's just making it easier. It's just, you know, organizing choice in a way that makes it much easier for you to figure out what to do.

- Richard: Oh, absolutely. I hadn't quite thought of that as being a piece, but there's absolutely lots of studies around choice paralysis, and even though some of those original studies by Iyengar and Leper back in 2000 have got a degree of skepticism around them now because people haven't been able to find the same scale of impact when they've re run them, there's a wonderful meta analysis by Chernev in 2015 where he looks at 50 papers on choice paralysis and says that, well, it is true that Sometimes more choice can be better, but he says this doesn't invalidate the finding.

- Richard: He says that for about half of the papers, reducing choice boosted usership. And he said what's interesting is there are four factors that can predict whether you've got the situation of choice paralysis, whether people don't have well defined preferences, whether they're unfamiliar with the options.

- Richard: And then going back to Spotify, I think the key one was if those, um, choices are kind of poorly, um, laid out. So what's brilliant about Spotify, they don't try and restrict the amount of songs available, but by your, you know, your daily playlists, the Discover Weekly, the Wrapped, they're giving you a handful of things to, to, to, you know, to, to, to get around that otherwise confusing mass of options.

- Kate Waters: Yeah. Yeah. No, I think, I think it's really interesting. And then there are nice little touches like the – um, it's in fact, one of my team told me about this. So, you know, when it tells you how many minutes you spent listening to a particular artist.

- All: Yeah. Yeah.

- Kate Waters: So apparently there's a, you know, this one is a principle called quantifiable fixation.

- Richard: Oh, yeah, I think I'm guilty of that.

- Kate Waters: So essentially, what it does is it gives you a way of validating the time that you've spent. So, you know, rather than just thinking, Oh, my God, I've wasted so much time listening, it's somehow by articulating it in a very Or in a kind of quantifiable way, you just sort of feel like it's, it's better, more like to be sort of time well spent.

- Richard: Yeah. Ah, no, no, fascinating. I think, um, I've certainly found when you can move a problem from being vague, like eat healthier, drink less, never moves me to action. But if you do a cholesterol test and you get a score, well then suddenly, you know, game on and There's something to work to and change. So I was interpreting quantifiable fixation in that one.

- Kate Waters: So I think it's probably an element of that as well. And actually it goes back to the example we were talking about before. Zoe does that absolutely perfectly. So it tells you what your cholesterol is or tells you what your sugar is. You know, so it does focus you on that, on making it very tangible and very specific.

- Richard: And maybe going back to that very first example you gave us about the British Heart Foundation, The previous problem was clogging of arteries is a very abstract thing. What that did is take something that's happening but invisible and make it visceral and noticeable. Now that did it through shock and awe in terms of imagery.

- Richard: But maybe there's a way to do it, as you say, with statistics and numbers if done well with ZOE and Spotify.

- Kate Waters: No, you're right. I hadn't thought about it in the context of the VHF. But, um, but that and that. That strategy of make the intangible tangible, make the invisible visible, was basically the strategy for what the government called health harms, that, well, and it still remains to this day.

- Kate Waters: So it was always, it didn't matter what you said, it just mattered, have you got a key image? Which is something that you, that makes something nasty that happens in your body when you smoke, you know, visible that you don't know about. So yeah, maybe it's, maybe it's a similar principle.

- Richard: Well, there's certainly in terms of memory studies, there's a, one of my favourite studies is a, is an Ian Begg study from 1972, where he gives people long lists of words and half of the words are abstract, like basic fact, half of the words are concrete, like square door, and when he says abstract, you can't.

- Richard: Visualise it, it's intangible, when it says concrete it means you can visualise it. And he found that when he gave people these lists of words, then asked them later to recall them, on average people remember 9 percent of the abstract phrases, 36 percent of the concrete phrases. There's this massive phenomenon.

- Richard: Fourfold leap in memory. And his argument was vision's the most powerful of our senses. So if you use language, people can visualize you're harnessing that. Even if it's a mental image, if you use language that's abstract, you are very easy to forget. So I wonder if Begg's study was very much about abstract concrete language, but the BHF example was.

- Richard: You know, turning something that was so intangible into an image that is seared into people's minds.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah. One other thing about Spotify Wrapped that I think is interesting is it, it tells you how you compare to all the music listeners on a specific topic. Like, you know, this artist you listen to more than 98 percent of other people, which to me strikes me as almost like an inverse of social proof.

- MichaelAaron: Usually you're looking for social proof to validate somebody else's decision and this kind of validates your own decision. I don't know if that, I don't know what that would be, but that's, it feels like that's a really compelling part of it.

- Richard: I think that's a great point because I wonder if that's a context point in that there are studies by Cialdini around energy usage where he called this the magnetic middle.

- Richard: He recorded, I think it's Californian households, how much energy they used, then sent them information the following month saying their energy usage and comparing to other people. Right. And what he found was if people had been using less energy, they started using more. Whereas if they'd been using loads more engine than their neighbours, they started using less.

- Richard: So he called it the magnetic middle. People essentially gravitate towards the norm that had been set out. So that first runs exactly counter the Spotify example, but he followed up that magnetic middle study with a third intervention, which was telling people how much they had used versus their neighbours.

- Richard: But if they had used less, he indicated this was a very positive thing. There was a giant smiley face. on their, um, on their, on their bill. And that pretty much got rid of the magnetic middle effect. So I wonder if what music does already, especially the language with, I think they call it, you know, you're, you're in the top percentage of fans.

- Richard: I wonder if all that language makes it feel like a very, very positive thing. I feel ridiculously proud of being, I think the top zero, zero, 1 percent of Nick Mulvay's fans. There's probably only 20 of us.

- Kate Waters: I wonder if it's, I don't know if it's anything to do with the fact that, Music is also such a powerful form of self expression, isn't it?

- Kate Waters: So actually if you are, if you are different from other people, maybe there's a principle where it's reinforcing your personal identity in some way. Um, you it's attractive to not be part of the crowd in this, in this instance, but to be. to be proudly different.

- Richard: Yeah, I think it's a fascinating one. And it is, I think, another example of, you know, context is hugely important and energy usage and music are different things.

- Richard: Yes. So if people come across experiments that are in wildly different settings, the thought should be, well, not to either accept those at face value unthinkingly or to reject them unthinkingly, but to repeat them. The academic study in their world in their category with their audience to make sure the what's true in one area works it works in another.

- Kate Waters: Yeah, I think the other the other things that has always struck me about Spotify and it taps it is something that you and I've talked about before, which is this notion of optimum newness, which is just brilliant. So where you get a playlist. Which is, you know, like it's, you know, it's based on, you know, you've listened to this artist loads of times.

- Kate Waters: So here's the playlist based on that artist. And it's, you know, it's maybe people that you haven't heard before, but they're pretty similar to the ones that you're already familiar with. So it's just that right level of, you know, it's not too different. It's to be a bit challenging, not too samey as to be boring, but actually just the kind of right amount of discoverability there.

- Richard: : I think that's that's a that's a brilliant one. And Michael and I have, talked in a previous podcast around Apple and their use of optimal newness. So when the iPhone was radically different, when it was launching, they used this principle of skeuomorphism, and rather than have a complete new set of icons for the functions of the phone, they tried to take very everyday items.

- Richard: So the recycle, function was a bin. The notes was a yellow. legal notepad. The podcast I think was a reel to reel tape recorder. That made this radical new technology feel a little bit more familiar, so not as scary. But when people become used to the iPhone, they don't need that familiarity any longer.

- Richard: And the icons become more and more abstract as time goes by. So I think Apple have been a very good user of that, that principle.

- Kate Waters: Yeah, no, it's really interesting. And I'm sure at the heart of it is, Is all just constant experimentation isn't that is the beauty of a platform brand. We just think every day is just a day of experimentation to work out what works.

- Kate Waters: You know, like, what's the, what's the, you know, and I think they, they are absolute masters of, um, I was going to say manipulating behavior, and that's not right, of understanding behavior and nudging it in the direction that is, that is most, you know, they, they want people together.

- Richard: Yeah, and great if you are a platform, but even if you're, um, if you're selling anything over the web, that's a giant laboratory, if you're a shop, you've got these laboratories, maybe a bit hard if you're an FMCG, but maybe you can create.

- Kate Waters: That's what Tyne Tees is for.

- Richard: Okay, okay.

- Kate Waters: So, so for anyone No, I don't know this. For anyone who's a very, very, very bad TV rep. We've GPs earlier - so Tyne Tees is an area of the UK, which is in the North East. And for years and years and years is where certainly Procter and Gamble and possibly Unilever as well, always used to test new stuff.

- Kate Waters: So if you were, if you were, you know, like a junior in an ad agency, you were always sent to Tyne Tees to go work out what they were testing. So it was, it was basically the hotbed testing grounds of everything. So, yeah. If you're an FMCG, that's where you go. That's where you go.

- MichaelAaron: Oh, that's so cool. The last thing about platform brands or any e commerce is I believe we really learned from Silicon Valley that data is what ultimately we should be following.

- MichaelAaron: So much in marketing and advertising history, it's the luminary creative director or the brand marketing decision maker that makes the final decision. I think what technology enabled Silicon Valley to do first, and now we're all trying to be as data driven as them is that, well, this is what we, we have proven to be true.

- MichaelAaron: And then that is how you get to those decisions, you know, that behavior change that you're talking about. Cause you were actually looking at what the final actions are.

- Kate Waters: Yeah, I think, I think you can. And I think, but what I would say is I think sometimes people think that you can swap out experimentation for, I guess what I would call true, true kind of creativity or innovation.

Episode Highlights

How changing the language we use affects how we relate to a brand

How Zoe applies social proof by making a normally invisible behaviour visible

How Spotify’s design helps to avoid choice paralysis

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.