00:00 / 31:54

Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: So welcome back, everyone, to Behavioral Science for Brands, a podcast where we bridge the gap between academics and practical marketing. Every other week we sit down and get nerdy on the science behind some of America's most successful brands. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: Today we're doing decoys trainings and the power of puzzles. Let's get into it.

- MichaelAaron: So, Richard, today we're starting with a publication that's truly close to my heart, The Economist. And it's so fitting that we chose The Economist because, A, it's a British publication and it's heavily read in America. We'll start with a little quiz. What percent do you think of all the readership of The Economist is American based?

- Richard: Oh 35%?

- MichaelAaron: 35%.

- MichaelAaron: A good guess, given they write with. Oh, you are. You know color humor, 60% of readership is in North America. And, you know, they're proudly a British publication, but read worldwide. And since the advent of digital, their newsletter and their online publications have really been one of the leading sources of news, evenhanded news in America and across the globe.

- MichaelAaron: But as we like to do, let me start with a little history of The Economist. Get everybody centered, thinking a little bit about the study that we're going to dive into today. So The Economist is a weekly British newspaper founded in 1843 by James Wilson. It's one of the most respected and influential newspapers in the world. The Economist is known for its high quality journal ism, in-depth analysis and witty, insightful commentary.

- MichaelAaron: Today, The Economist is one of the most widely read newspapers in the world. Circulation in print of over 1 million copies, and it's available in 175 countries each week. Our interest in The Economist really got started with its reputation almost unique in the publishing world and a lot of its fame. Born out of an advertising campaign that started in the late 1980s by an agency here in the United Kingdom.

- MichaelAaron: And Richard, you were just telling me a little bit and V is a storied agency for our American listeners. They may not know AMV.

- Richard: Yeah for most of the eighties, nineties, early 2000, it was it was by far and away the biggest agency in Britain. Its only recently lost that crown

- MichaelAaron: and sometime in the last 20 or 30 years.

- MichaelAaron: Rich and I are not. Ad agency experts bought by BBDO

- Richard: Merged

- MichaelAaron: Merged is the more politically correct way to say it. So the ads that flowed out of AMV in the late 1980s were part of what they called the White Out of Red campaign. So that's what we're going to focus on today. And really, this is an award winning campaign known for its witty advertising, sophisticated, playful.

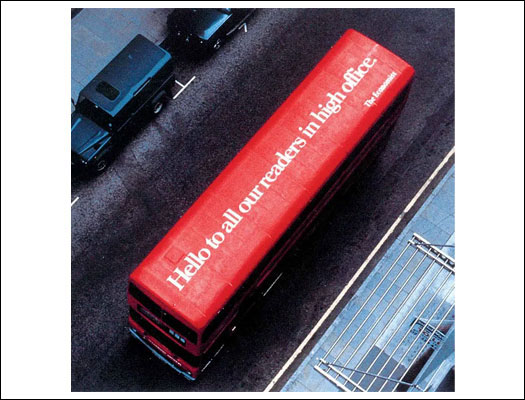

- MichaelAaron: But what we really care about, wildly effective between 1988 when it launched in 2001 circulation for The Economist rose 64% against a market decline of 20%, so seriously outstripping the competition. Prescriptions during this time almost doubled. Not only did they propel the magazine, creative director David Abbott became famous because of these ads. So we're going to put in the show notes some of these great ads.

- MichaelAaron: Richard, give the set up for our audience when we're talking about these ads. These are not fancy 32nd TV spots.

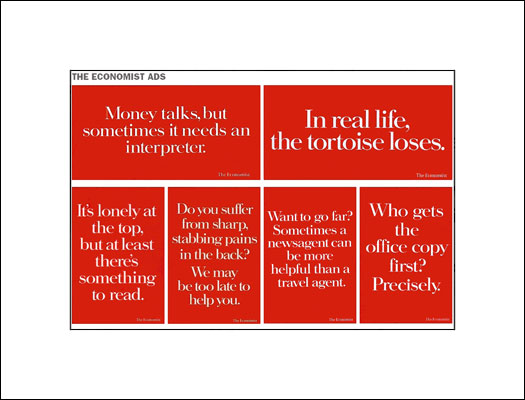

- Richard: No, they're almost invariably print ads or poster, rights. So they're very simple, always red background, white font in a dozen or so words, but very witty and very pithy.

- MichaelAaron: And the red background and the white type is mimicking the logo.

- Richard: Exactly. Exactly. Yes the masthead of the Economist's famous. Exactly the same colors.

- MichaelAaron: So. So sometimes they use wordplay. "Great minds like I think", The Economist. And sometimes they make it. They make you stop and think. Here's the headline from another famous ad in this series. "Lose the ability to slip out of meetings unnoticed", The Economist. You know, just you read it and you say, well, why would that be?

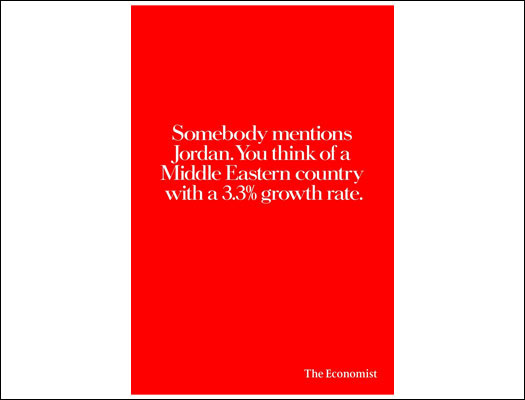

- MichaelAaron: Oh. Because I'm actually adding something in the meeting. I'm actually helping the conversation. Here's one a little bit longer, but maybe still within the 12 words you call down. Somebody mentions Jordan. You think of a middle Eastern country with a 3.3% growth rate. Now, when I hear Jordan, I think basketball famous star Michael Jordan, You think?

- Richard: I think celebrity model of the 1990s.

- Richard: Anyone in their forties who's British will will remember.

- MichaelAaron: But what the economist what the ad is telling us is you'll be more sophisticated by reading The Economist. You'll know of the Middle Eastern country, Jordan and Richard, probably the one of the most famous in the series. "It's a quote and it's five words I never read The Economist", Management Trainee, age 42.

- MichaelAaron: And when you listen to it, it's almost it's a great ad. Why one. The Economist is in the headline so you don't need to attribute it to the brand, to you read it and you say, oh, why would that be? And then you realize management trainee at age 42 years old. This is not a successful person. So it makes you feel like if I read The Economist, I'll be more sophisticated, I'll be more knowledgeable, I'll be more successful.

- MichaelAaron: A lot of psychology coming through in these witty, humorous ads.

- Richard: Yes, But I think they are linked by one key theme. So as I alluded to, every one of the statements isn't a direct play about why The Economist is amazing. It's a little puzzle for the audience to solve. Now, behavioral scientists would say that is a very sensible way of boosting recall.

- Richard: I think what's interesting about those examples you mentioned is they are all using essentially the same psychological tactic. Every one of them is not communicating directly. They're not simply stating the value of benefits to the Economist. They create a little puzzle and the audience have to resolve that puzzle to understand what's being said. So that's not a throw away approach.

- Richard: There's a lot of psychological evidence that suggests that will boost memorability. So the key study comes from to University of Toronto psychologist Graf And Slamecka. And back in 1978, they run a small study. They recruit a group of students and they give them a list of words. So half the students see a list of animals. Cat. Dog. Elephant. Lion.

- Richard: The other half see the same list of animals. But this time there is one letter missing from the word

- MichaelAaron: c. T missing the a.

- Richard: Exactly. Both groups get exactly the same amount of time to read through this list. The psychologist then take the list away and ask people to recall as much as they possibly can. And that key finding is the group that had to generate the answers themselves.

- Richard: They remember 15% more information than the group who were just given the information on a plate.

- MichaelAaron: So if I work to solve the puzzle, if I fill in the missing letter, then I have higher memorability than if I just run it alone.

- Richard: Exactly. To really engage our memory, you need to encourage the audience to a little bit of effort.

- Richard: And it's the act of generating the answer that creates memorability. And because it's all around this generation, that's what the psychologist named the insight. They call this the Generation Effect. If you give the audience the information on a play, if you make it very easy for them to understand, it tends to wash over them. They tend to forget it.

- Richard: You've got to add this little bit of grit in the result.

- MichaelAaron: And so that's what they're doing with The Economist. In the last example, we talked about management. Trainee 42. If you just read it, you might just watch right over. But if you stop it, you've got to decode it a little bit. If I'm 42 years old, I'm not a very good management trainee.

- Richard: And that that particular line, which spurred by my favorite, that's interesting as well, because if you think about the underlying message of The Economist, it's actually a little bit nasty. The message is, if you don't read this magazine, you're a failure.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, right.

- Richard: Now, if you said that directly to someone, they would be irritated that, you know, how dare you call me a failure?

- Richard: But by wrapping up the message in a little bit of humor and with a bit of weight, allows you to communicate something that might be my land badly otherwise.

- MichaelAaron: So, Richard, the 1978 Graf and Slamecka study was a small sample size, wasn't it?

- Richard: Yeah, I think it was about 24 students.

- MichaelAaron: And that always causes a little bit of.

- MichaelAaron: Well, is this really applicable to a wider use case?

- Richard: Absolutely. I think you're right to have a little bit of skepticism towards it. The sample size is very small. So how robust the numbers. And then secondly, maybe more problematically, they used a student sample as students and not a representative group. So can you extrapolate the findings from students onto the population as a whole?

- MichaelAaron: Right.

- Richard: But if you hear studies like that, the reaction shouldn't be to dismiss the finding and forget about it. What we can do is rerun the studies with a more robust sample. So all the information is in the public domain and the methodology of Graf and Slamecka is there for everyone to use. So back in 2020, Mike Duhon and I reran their study, but we used brand names sometimes to keep a full name.

- MichaelAaron: Sometimes we took out a letter, we got a sample of 415 people

- MichaelAaron: much better.

- Richard: Yeah, this scale issue. And more importantly, they were nationally representative.

- MichaelAaron: and this was run in the UK.

- Richard: This was run in the UK

- MichaelAaron: go for it,

- Richard: but you could easily reporting to us as well. Yeah. And we found very similar findings to the original work.

- Richard: So I think for us it was a 14% improvement in memorability. When people had to generate the answers themselves

- MichaelAaron: and the original study was 15%

- Richard: 15%. Yeah, yeah.

- MichaelAaron: So pretty much the same answer.

- Richard: So the some of these old studies in the 1960s and seventies where they use a student sample, I think they I often treat them as unproven hypotheses.

- Richard: What you want to do is rerun them in a more robust set of conditions using more commercial stimulus.

- MichaelAaron: And in that often what we've come to believe now and in many episodes in together, that what we're really talking about are more human truths, are more based on people's nature. And we're uncovering them through multiple academic studies, and we just keep rerunning them to make sure they can they still apply.

- MichaelAaron: But they really are part of the human condition.

- Richard: Absolutely. I've never heard of a a robust study that has become irrelevant over time.

- MichaelAaron: Right.

- Richard: I think, yes, there are occasions where the sample size was very small.

- MichaelAaron: The result was a statistical fluke, but where something's been shown in the 19 3940s in a decent setting, those findings don't fade.

- Richard: The study by scientists study of the fundamentals of human nature.

- MichaelAaron: And I think, you know, and for you and I, we created this podcast because marketing and advertising so often doesn't refer to academics because it's dense, because when it comes out of university, it's sometimes it's hard to see the connection to the commercial application. So for you and I, this is about taking things that we've read at studies that have been well regarded and saying, well, how can we apply them?

- Richard: Yeah, and academics don't do themselves any favors here. There's a wonderful phrase, slightly derogatory phrase about psychologists. People say they've got physics only. So if you read the original papers, they are overflowing in unnecessary jargon, overflowing in unnecessarily complicated statistics. And I think they're trying to prove to each other, trying to prove to their peer group that this is a serious, rigorous academic study.

- MichaelAaron: The longer the words, the better.

- MichaelAaron: But yeah, hopefully that's their approach. But if you pair the studies back to have basics, these are simple, powerful experiments that have a really powerful everyday use at practical use.

- Richard: And what do we say to our clients whenever we get engaged to bring behavioral science to brands? We say, Why is it I'll let you do the pitch this time?

- MichaelAaron: Why is it that marketers and advertisers should be focused on using behavioral science in their work?

- Richard: Well, I would argue we're all in the business of behavior change, and literally everyone who works in marketing is trying to sell more, get customers to pick more of their brands, get customers to pay a premium. You know, everything we're trying to do is about changing the behavior of other people.

- MichaelAaron: So my question is always, why wouldn't you rule out 130 years of robust experiments into what makes for effective by the change? And even if you have amazing strategists, great creatives, brand brand side folks that know their brand better than anybody else, behavioral science gives you the roadmap for how to make that insight, that strategy, that creative, repeatable may you meaning that it's not just lightning in a bottle, it's that I can count on this approach to continue to provide results for my brand.

- Richard: Yes. If you don't use behavioral science and you look back at phenomenally successful campaigns over the past, each campaign has hundreds of different elements. How do you know which of the elements drove that success? But if you know about the body payroll science experiments, you can see the levers they're using in those successful campaigns. And therefore, it makes it easier for you to repeat that that success.

- MichaelAaron: There's everyone there's our argument for why we should all be reading, thinking and doing more with behavioral science. But we digress. So getting back to The Economist, Richard, if this was so successful for them, why stop running the campaign?

- Richard: Yeah, I think that's a great question because you see this happening quite a lot. Brands have an amazing, powerful, long running campaign.

- MichaelAaron: Yes,

- Richard: they then stop running it. And what tends to replace it is something that is more average, more mediocre. I would argue that the psychological bias at the heart of that is overconfidence.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: There's an awful lot of experimentation from psychologists that suggests people tend to be overconfident. So, for example, most people think they're more intelligent than average.

- Richard: Most people think they're better looking on average. Most people think they're more moral than average. But of course, that can't be the case. But my favorite studies in any area comes from, I think, the University of Southampton Psychological set of kids. He goes to young offender institutes. So these are people who are locked up for crimes. And he asked them about their ethics.

- Richard: And even this group who are in jail for a crime, they believe they're more ethical than average. So you see this happening again and again and again. Everyone thinks they're better than average. That's a problem in marketing because if you think you're better than you are, you will believe it's easier than it is to create an amazing campaign.

- Richard: So I think what happens is people jettison these brilliant, powerful, well-proven campaigns because they think their own abilities will make it easy to repeat. The success was actually it's much higher than that. The likelihood is if you jettison a burning campaign, you're going to end up with something closer to the average.

- MichaelAaron: And you and I have often talked about this when advising brands, sometimes the incentives for the brand managers or the new agency are not always aligned with what's best for the brand.

- MichaelAaron: Meaning, I've just had a new brand manager come in or I've just hired a new agency. What do you expect to them?

- Richard: Yeah, this is not behavioral sciences. It's just a straight economist. But there's an economist called Steven Ross. He talks about this. He calls it the principle agent problem.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: He says companies have a principle that the shareholder, the company itself, and they have agents, So the staff, the marketers.

- Richard: And he says there is often a digression of incentives.

- MichaelAaron: What's best for the principal is not always best for the agent.

- Richard: Exactly. Principle wants long term, sustainable, profitable growth. Now, the agent, of course, they want that. What they also want is stellar career progression

- MichaelAaron: and bonuses

- Richard: and bonuses and fame and the admiration of their peers. Now, if you just continue a long standing, successful campaign, you might get some plaudits, but you're never going to get, you know, absolutely fine if you believe you can change that campaign run, saying equally successful, that's completely new.

- Richard: That's an amazing garland and your CV. So I think you're absolutely right. It's as much about the logical, rational motivations of the staff as what's right for the brand.

- MichaelAaron: And so when we think about how to make profitable, healthy brands, which is all of our goal, whether we're on the brand side or we're on the agency side, we always have to remember that what, what, what may be driving that brief or maybe driving that assignment may not be what's best for the principal.

- Richard: Yes. And I think there are a few of the if you are the brand, you ought to be looking at how come in line the incentives, all the different players, because if you don't, there's going to be problems down the line.

- MichaelAaron: You known on the topic of aligning incentives, really has a whole interesting history for brands and brand marketers going back to when advertising really got its modern day launch with the creation of TV and the advent of multiple stations and multiple opportunities for brands to get in front of consumers more and more.

- MichaelAaron: You know, the original compensation model was all commission based, which was, you know, the agency buys the TVs spot time and they get a percentage. 15% was the old model of all the of all the of all the ad space that they bought. And in some ways, that was a way that if the ad worked and it continued to run and they bought more placements, the agency made money as the brand saw success of the creative.

- MichaelAaron: In some ways we walked away from aligning incentives, even if that was not the primary intent of a commission based model today, where really agencies are seen more as interchangeable vendors and anybody can have a great idea and the incentives aren't as aligned. But we could do more. I think it'd be interesting to talk more about that.

- MichaelAaron: Certainly the companies that I've started, Method 1 and Function Growth have really innovated on agency remuneration because we are seeking to find ways to align incentives. And it's just an interesting part of how we grow brands today.

- Richard: Yeah, I think the ROI around looks like concern about that. The commission model, there was an old joke about media agencies, which was the answer Spend more Now what's the question?

- MichaelAaron: And, and this is why we have the industry that we have, because we haven't found a way to align the incentives the way that we want. Okay, Richard. So getting back to The Economist, so we've talked a lot about the generation effect and how that's really helped distinguish the economist advertising. What behavioral science has the Economist employed?

- Richard: So you're right, the generation effect is probably the most famous bias they've used. It's the one that was the heart of their long running campaign. But these insights don't just have to be used in creative. You can also use them at the point of sale.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: And there's a really famous study that Dan Arielly, which was on The Economist, and it was a tactic they used to encourage people to spend a little bit more.

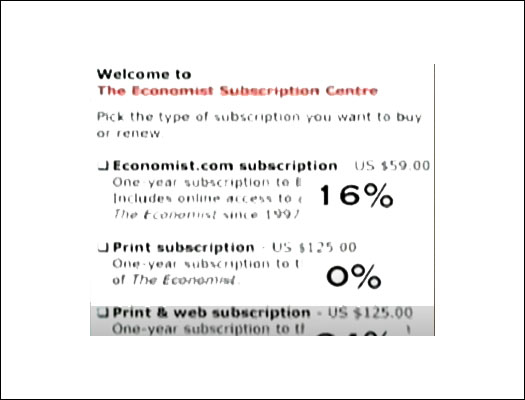

- Richard: So I really set up a study research group of people. And for half the people, he says, okay, do you want to buy an online only subscription to The Economist for $59? Or do you want to spend 125 on a dollars on a print and online subscription? And when there's that set up, 68% of people go online, only 32% go for the print and online version.

- Richard: So you've got that 2 to 1 in favor of the cheaper option.

- MichaelAaron: Right. Makes sense.

- Richard: Yeah. Group of people, you've got the same two options, $59 online, $125 print and online. But he throws in a third option, $125 print only.

- MichaelAaron: Same price.

- Richard: Same price. But you're not getting the online option. Now, obviously, that's a bloody awful offering, so no one picks that.

- Richard: But what's interesting, what's of interest, of course, is the shift in the ratio between the other two options. Now you get a complete role reversal. Now you've got 84% of people picking the print and online option, 16% picking the online only option. Now, why this happens, Ariely argues in that first out, it's very hard for people to know what to buy because there's a trade off.

- Richard: You either get cheap and low quality online only or you get expensive and high quality print online. You've changing two variables at once. So people find it hard to know what's the best deal.

- MichaelAaron: Too much is changing at once.

- Richard: Exactly. But in that second option, once you throw in the obviously awful print, only $425, what is absolutely obvious is the print and online is better than that.

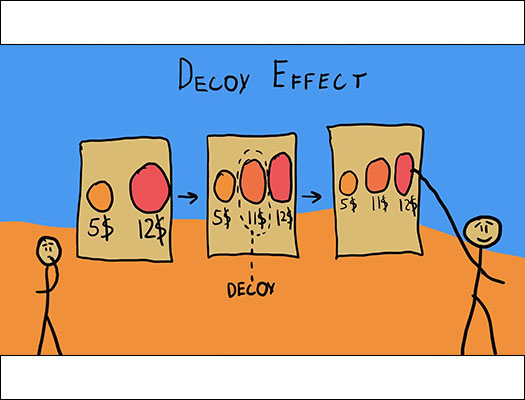

- Richard: It's higher quality and it's exactly the same price. So psychologists would call this the Decoy effect. The argument is that the print only viable option is asymmetrically dominated by print and online. And what people tend to do is when they're faced with a complex question, they often search for a simpler question that gives them an almost good answer.

- Richard: And what's very simple to see is that that premium option is better. They forget about the original trade off and just go for the obvious answer of print and online. So this is a really interesting tactic that doesn't get applied, I think, enough in e-commerce. And it's the idea that if you have two options, a basic option and a premium option, if you want to steer people towards the premium one, introduce an obviously an easily comparable inferior option to the premium.

- Richard: That's the decoy effect and it can boost average purchase value.

- MichaelAaron: And really interesting and you know, when we've done work at shopper marketing at the shelf, we've often come to believe that they're not deciding what to choose. They're deciding what not to choose. They are at shelf. They're selecting options. I don't want this shampoo. I don't want that shampoo.

- MichaelAaron: This is what's left. So it's almost a process of selecting. And when you have a decoy effect like this, it helps you start the selection process and move your focus.

- Richard: Yeah, I think you're right. You can obviously knock out the print only version, but it also helps you do is recognize that there is one other option out of all the others available that is better on both quality and well, equal on price.

- Richard: So it steers people towards that being the easily noticeable superior option. And what they don't want to get involved in is that complex calculation of, well, what's this value price trade off is the really cheap option of online only worth investigating.

- MichaelAaron: Even hearing you say this in the beginning option, the first half of Ariely study, I'm saying to myself what?

- MichaelAaron: I read the print magazine each week. How much more value is it? Would I like to have it more or less than online? And then as soon as you introduced the second option, I forgot all about my desire for print and all I could think was I don't want this. Obviously the worst choice.

- Richard: Your focus is drawn to the oh, I get online as an extra benefit, you know, all those other equally valid questions.

- Richard: And what's interesting is in a world of complexity, you can steer people's attention to a particular comparison and what you're doing is steered towards a comparison. This reflects well on your most premium option.

- MichaelAaron: So the takeaway for marketers here is if there is a choice to be made, we can help steer people in the right direction by giving them an obviously bad choice to get in the right direction.

- Richard: And sometimes the best way to sell something is not the most direct. This is introducing a decoy option that is a little bit more oblique. But as long as you're measuring this properly, you'll see the positive effect of that decoy option.

- MichaelAaron: Well, it's interesting that you bring up measurement because so often we sit in the room and we look at an analytics dashboard and we say, Well, wait a second, this third option is not getting any clicks.

- MichaelAaron: It's not getting purchases. Kill it. Yeah, but that would be the opposite of what we're learning here.

- Richard: Yeah, I think you're actually right that an overly literal interpretation of data ends up with suboptimal results. You can't just say, Well, let's kill the zero selling option because it will have repercussions elsewhere. It was designed to be a zero selling off intention was for it to be zero selling.

- Richard: And I think that's what happens very often. You know, brands introduce these types of options. They see that they're not selling much directly and therefore they remove them. But if you look at the entire volume of revenue generated, if you look at it more holistically, then you see that benefit.

- MichaelAaron: So if you're doing e-commerce, we would recommend doing an A, B test with the option that we just talked about with the decoy and then the entire thing with no decoy and compare those options rather than just looking at the effectiveness of the decoy itself.

- Richard: Yes. And as you say, it has to be an AP test. You can put these two options in front of

- MichaelAaron: the same person. The same person can't see both. Is that one?

- Richard: They would think you're insane to even suggest this is an approach

- MichaelAaron: that's interesting, you know. And the other thought I was having was this generation effect is a little bit at play even in the decoy because you're doing a little extra work in order to cancel out the decoy.

- MichaelAaron: Is that have any standing in your mind?

- Richard: I hadn't actually thought that I'd always flipped it on the other way round, which is the original two offers.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: Even though there are fewer items available because there's a trade off of quality and value, I would say that's the complexity. I think you're actually reducing complexity here, but I actually thought of it in looking at that way.

- MichaelAaron: So the dopamine hit for me when I read management Trainee 42 and I figure it out is a little bit like when I see $125 for printing online or just print and I say, you know what, I got it. You're going to be printing online.

- MichaelAaron: So that's a fair point that you don't mean. Here is, Oh, I've, I've pulled on over on the system.

- Richard: I'm going to think that is obviously better yet. Okay. I like that. That's an angle where we're figuring it out together as we go.

- MichaelAaron: Very cool. Very cool. All right. We're coming to the end of our time together. But before we do a generation effect decoy. Richard, outside of The Economist. What other ads have you seen in the world that really strike your fancy out using these behavioral science biases?

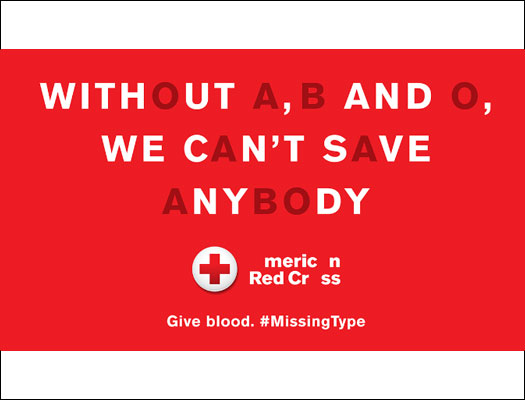

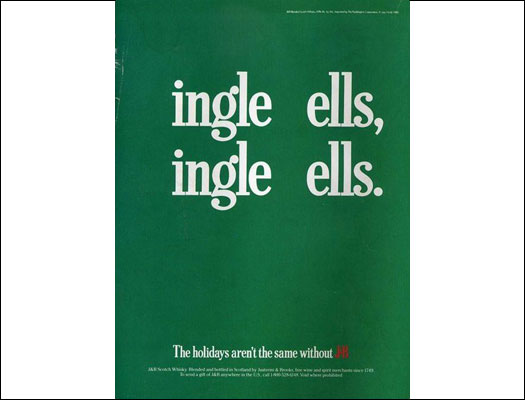

- Richard: Well, this for the generation. In fact, there's a really nice series of GMB scans.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: And they had a classic Christmas ad back in the 1980s where it said, you know, blank bingo owls. And the point was, you know, you're meant to realize that it's Jim that's the missing ingredient. I think that's lovely to play on how to add JMB to anything in it, and it makes the festive season better.

- Richard: So I quite like the job ads. Those are amazing.

- MichaelAaron: We'll drop, we'll find the example. But in the show notes and for me, you know, I was thinking about the decoy. In fact one of the most famous examples of decoy pricing that I know of is when Apple first launched their Apple watches. They had three prices, always a best practice.

- MichaelAaron: They had the the base watch, which was for 99, they had a premium watch, which was 599. And then they had that same premium watch with a Hermes wristband for 1499. Easy for people to choose to select the 1499 Hermes wristband and go with the 599 premium watch versus just having two options a 499 and a $599 watch.

- MichaelAaron: So another great example of how you can add a third option, not even change the tech, not even change the product. Just add a simple extra feature like a design or wristband and really drive a lot more purchases of the $599 watch.

- MichaelAaron: So, Richard, let's wrap it up for everybody today. What did we learn in this episode?

- Richard: We learned two big things.

- Richard: The first is the benefit of involving your audience in interpretation of your ads,

- MichaelAaron: Right.

- Richard: That if you allow the audience to generate their own answer, it tends to be more memorable than just giving them the answer on a play. That was the work of Graf and SLamanca that we discussed this idea of the generation effect, the second big thing we discussed is around the decoy effect, and that's the argument.

- Richard: The people don't respond to prices in a completely rational way. If you can introduce what's called a decoy option and obviously a worse version of the product than your most premium one, you can steer people's purchase towards that obviously superior premium option.

- MichaelAaron: Thanks for that summary. Thank you. Thanks again for tuning in today to the Behavioral Science for Brands podcast, I'm Michael Aaron Flicker.

- Richard: I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: We're always looking for new topics. Please visit us at TheConsumerBehaviourLab.com. Fill out our form. Drop us a line on our social channels or email us at [email protected].

- AD: Behavioral Science for Brands is brought to you by Function Growth AdAge’s 2023 Newcomer Agency of the year. Function Growth uses behavioral science to supercharge growth for direct to consumer brands.

They operate across a wide spectrum of services as a one stop shop and integrated strategic partner for brands with high growth potential. Unlike typical agencies, function growth leverage is shared risk and reward compensation models, meaning they only make money when your brand grows, reach out to them. If you'd like to unlock the power of behavioral science to accelerate growth for your brand.

Episode Highlights

The Generation Effect

The Economist's ads don't directly communicate the magazine's value but instead create puzzles for the audience to solve, making them more memorable.

Decoy Effect

The "decoy effect" strongly influences decision-making as demonstrated in Dan Ariely's study involving The Economist's pricing options to encourage people to spend more.

Aligning Incentives

There is a strong importance of aligning incentives between brands and agencies in order to achieve long-term, sustainable growth.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.