Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: So welcome back, everyone, to Behavioral Science for Brands, a podcast where we bridge the gap between academics and marketing. Every other week we sit down and decode the science behind some of America's most successful brands. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: Today we're doing How Snickers use trigger moments to drive consumption. Let's get into it. So, Richard, today we're just having fun.

- MichaelAaron: We're talking candy bars, your favorite candy bar growing up as a kid?

- Richard: A Wham Bar.

- MichaelAaron: A Wham Bar! Describe for our American audience, our mostly American audience, what a Wham Bar is?

- Richard: It was a very, very chewy, sweet

- MichaelAaron: Got it

- Richard: In a bar. And it had these little sprinkles in the middle that kind of popped on your tongue.

- MichaelAaron: Like literally popped as you as they sat on your tongue

- Richard: I think you still get them now.

- Richard: But I remember them as being like the size of your head, almost pennies. You buy them. And now they're just that. They call it Shrinkflation.

- MichaelAaron: They're getting a little smaller in size, half your thumbnail. I was trying to think of the word Pop Rocks in America would be those that you put on your tongue and they snap, crackle, pop.

- Richard: Sounds like this that

- MichaelAaron: Pop Rocks too funny. And today's candy bar of much interest is the Snickers Bar, one of the most popular candy bars in the world, accounting for over $2 billion worth of annual sales for the M&M Mars Company sold in over 80 countries enjoyed by millions of people each year. But before we go deep on Snickers, I was surprised to learn that Snickers was not Snickers in your homeland of the United Kingdom.

- Richard: That's right. For most of my childhood, it was called a marathon. And then too much consternation for it was about 15 or 16. They changed the name to Snickers. Hey, it's a myth Now, that's a distant memory, but quite a lot of candy bars did this way. They would be different names, different countries, and eventually they rational, rational to rationalize

- MichaelAaron: rationalize

- Richard: rationalize them.

- Richard: Yeah. Starburst, I think you call them.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: Opal Fruits, originally

- MichaelAaron: Can you spell that for the listeners at home?

- Richard: Opal is like the gem. O, P, A, L.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah

- Richard: And then fruits which I guess is the same spelling.

- MichaelAaron: Yes Opal fruits were Starburst marathon bars were Snickers and and you call them and I call them pop rocks

- Richard: and we had a name for them.

- MichaelAaron: Okay.

- MichaelAaron: So let's do a little history on the brand, the Snickers brand, Snickers bar. For any of you who have not had this delicious candy is peanut nougat and caramel. The chocolate coating was not there when they started the brand. It was added in 1937.

- Richard: An agency had a biscuit brand and I remember them seriously discussing whether one of their messages should be.

- Richard: And now with real chocolate, I think they eventually realized that people would start to think about What the hell are you feeling? It's the last. I tell you this is in about 2005. You can't get away with that. You said,

- MichaelAaron: You know what? Let's not leave it out. Let's leave it out. Snickers famously used in movies, TV shows.

- MichaelAaron: It's been on The Simpsons. It's been in Seinfeld. It was featured in The Hangover movie. Fun fact, the largest Snickers bars, Richard, was made in 2012, weight over £1,000 and 10,000 peanuts, which made me think how many peanuts are in a regular Snickers bar

- Richard: That's quite a mean ratio. Would that work out like ten peanuts a pound for that big one? So hopefully they're putting a bit more generous.

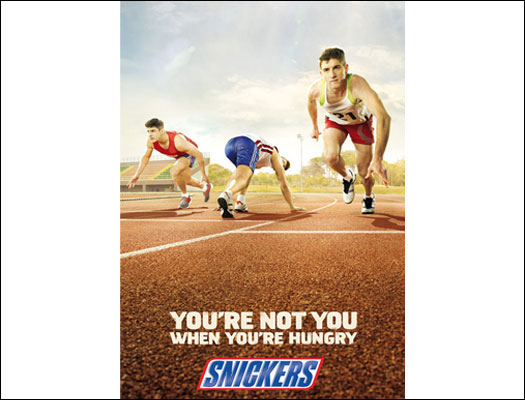

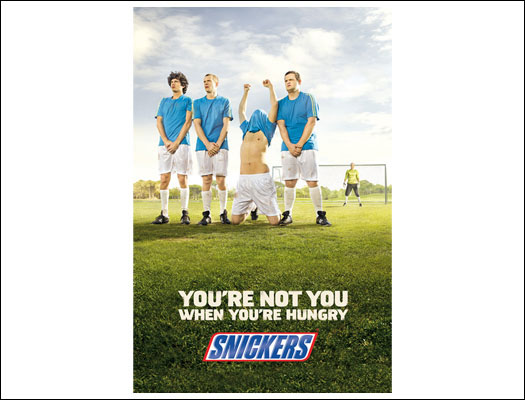

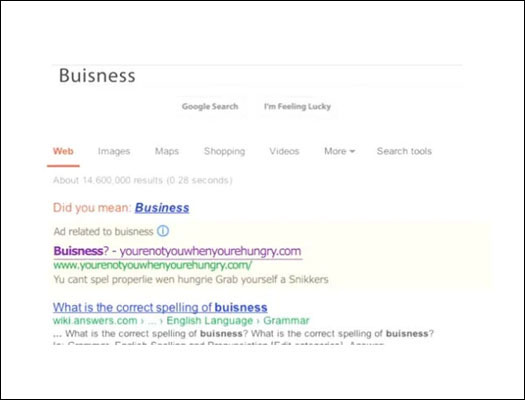

- MichaelAaron: They're only a little bit more 16 peanuts in every Snickers bar, 16 peanuts and every Snickers bar. I don't know what to do with that. They're so delicious. Candy bar, best selling candy bar today. Obviously, the brand, the product itself is excellent, but a lot of the success is attributable to this epic marketing campaign, you're not you when you're hungry, you're not you.

- MichaelAaron: When you're hungry. Created by BBDO. First year that they launched this campaign, a 15.9% increase in global sales.

- Richard: That's impressive for such a big brand. Actually, it is already one of the world's biggest.

- MichaelAaron: And really built on an insight that came to life through the creative.

- Richard: Yeah. What I like about this campaign is they use a very simple idea from psychology.

- Richard: But even though it's simple. Most brands do not do it. So the experiment I want to talk about, which give us a bit of evidence of this, is an experiment by Sarah Mellon, who's at University of Bath.

- MichaelAaron: We've just heard before.

- Richard: Yeah, I think we have.

- Richard: Yeah. So a couple of which actually we used it in, but she ran a study back in 2002.

- Richard: Very simple. She invites 228 people into a lab, randomize them into three groups. First group, the control are just invited in, given a diary, and then told to record all the exercise they do over the next two weeks. Now, when they come back two weeks later, 35% of them have exercised at least once a week for 15 minutes.

- MichaelAaron: That's the that's the basis, '

- Richard: the benchmark.

- MichaelAaron: Got it.

- Richard: Next, two groups. She then tries to boost that number. So second group, she brings them in, gives them the diary, and then place them on motivational video about the wonders of exercise. And even though this group come out of the video say they are enthused, pumped up, excited about exercising when they come back two weeks later, there's barely any increase in expense levels.

- Richard: So 38% of them have exercised at least once a week. She calls this the intention to action gap, which is essentially the idea that if you motivate people to want to do something

- MichaelAaron: high in tension,

- Richard: high in tension, doesn't necessary convert to behavior change. Now that I would say is a repeated mistake of advertisers, what they focus on is boosting appeal or boosting motivation.

- Richard: But Moon says that's not enough. Motivation is a necessary but not sufficient condition for behavior change. So a final group she tries to unearth that missing ingredient. She invites that group into the lab, give them the diary, plays in the video. But then she says to them, Tell me when, where and with whom. You are exercising.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: That group comes back two weeks later and you get a massive change. 91% of them have exercised at least once.

- MichaelAaron: Wow.

- Richard: So you jump from 38% with the motivated group to 91% with this group. What me argues is that by getting people to stay when and where they're going to exercise. So I might say, okay, I'm going to exercise the gym on a Thursday evening when that moment comes around, when Thursday evening comes around.

- Richard: I'm reminded of this vague aspiration to exercise, and in it by being reminded I move to action. That cue or trigger moment acts as a catalyst convert intention to action. Now her argument is loads of people forget to do that. They create the motivation, but they don't create this cue or trigger moment. What's so brilliant about Snickers is they are very clear on the trigger moment.

- Richard: They are very clear about what moment you should consume their products when you're hungry. They associate this feeling of hangry. Nurse or tiredness or confusion through hunger with purchasing a Snickers. It's very simple, but it's a very powerful way of converting intention to action.

- MichaelAaron: We even see in the sales data at airports, Snickers bars are the number one candies sold over Milky Way.

- MichaelAaron: Because Milky Way is seen as an indulgence, Snickers is seen as a meal replacement. So we even see in our own data that that insight is borne from data that they have about where they're being aware, where their sales are successful.

- Richard: What you've done is you've associate purchasing your product with a particular time, place or mood. What other brands need to do is think, Well, okay, we think we've made our candy bar, our trainers or our gym membership appealing

- MichaelAaron: right?

- Richard: How do we create this time, place or mood that people associate with us? It's not enough to just make it appealing. We need a trigger to actually get people to use the product, buy the thing, use it again. And if you look at some of the best ever campaigns, you see this happening again and again. So Kit Kat for probably 60 or 70 years made a break from that.

- MichaelAaron: Exactly. Or my favorite example. Champagne.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: So you think about wines. There are loads of beautiful tasting wines, but none of them sell half as much as champagne. Champagne is a multi-billion pound industry because they have brilliantly fuze the product with a particular feeling. Celebrations. My mum hates drinking. She doesn't even like champagne, but knew that if you go out and buy a bottle because it's the thing to do.

- MichaelAaron: That's right.

- Richard: It is so well read in people's mind that even if I don't like the product, end up purchasing it. That I think is a huge scale example of a brand very successfully identifying very clearly and concretely a particular a particular mood that they're associated with.

- MichaelAaron: We're going to dig deeper into this actually in a future episode coming up on diamonds and the moment of when you should buy a diamond as an engagement ring.

- Richard: Yeah, and that was a major success of that campaign as well.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah DeBeers, brilliant campaign.

- MichaelAaron: So Snickers clearly excellent at drawing this connection between hunger and using Snickers to satiate that hunger. What other behavioral science has Snickers employ in their campaigns?

- Richard: I think the way you can differentiate them from all those other brands we mentioned, Kit Kat or Champagne, is they have an created just a dry trigger to purchase everything about you're not you and you're hungry is about comedy.

- Richard: It's trying to be as amusing and witty as possible.

- MichaelAaron: It's not just a protein bar.

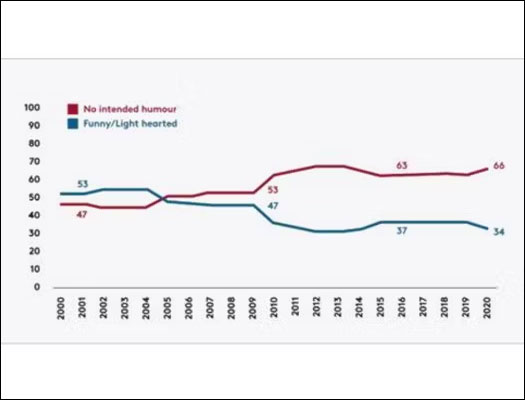

- Richard: It's not. Yes, exactly. And that's, I think, interesting because it's quite different from how most brands behaving. There's an awful lot of evidence the brands are moving away from the humor and cans have done an amazing bit of analysis. 200,000 plus global ads and back in 1990, 53 of them aimed to amuse people.

- Richard: By 2020, it was down to 34%. So advertisers are moving away from humor as a tactic to sell. Now, that can today it should concern us all because humor isn't a nice to have. There is an awful lot of evidence that shows that you can boost recall and other benefits by behaving humorously. So one of my favorite studies in the area is by Baynes back in 2014 works with a group of old people, tests their memory, so they give a list of information and then they are asked how many of the words they can remember.

- Richard: Half the group then go from what a humorous video. Half the group watch a less funny video. He then gives the list of words again, asked them to recall as many as they can, and he finds that there is a much greater uplift on that second attempt at doing the task. Amongst people who'd been primed with the humorous video.

- Richard: So I think it's a 44% uplift amongst them for a 20% uplift amongst the non humorous group. So you have many studies like by in this study that showed this benefit of humor. But maybe what's most powerful is it's not just one off studies. There's a wonderful metro analysis by Eisenhardt who I think he's an Austrian psychologist, so he looks at 38 different papers and experiments on humor and finds the repeated result that if you use humor, you boost recall of the product speech, record the brands, you boost positivity, and probably most importantly, you boost purchase

- Richard: Intent.

- MichaelAaron: Mm hmm.

- Richard: So there is a really powerful, robust dataset that's suggests humor is one of the best tactics a brand can use to increase positivity.

- MichaelAaron: Why do we think that humor has been less used over the last 30 years? Why has it been on such a decline?

- Richard: I think that is a great question. I think one reason why it's dropped so much is that we've obviously had quite a lot of events happening over the last 50 years, to say mildly.

- Richard: You know, we've had financial crashes, we've had COVID pandemics. And I think the reaction of the ad industry has been, well, at times of trouble. We need to show empathy.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: But what people want is not fake empathy from their bank or their car. It's just not believable. I think what people actually want at times of trouble is a little bit of light relief.

- MichaelAaron: A respite.

- Richard: Yes, exactly.

- Richard: That's a reasonable thing to expect from an ad.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah,

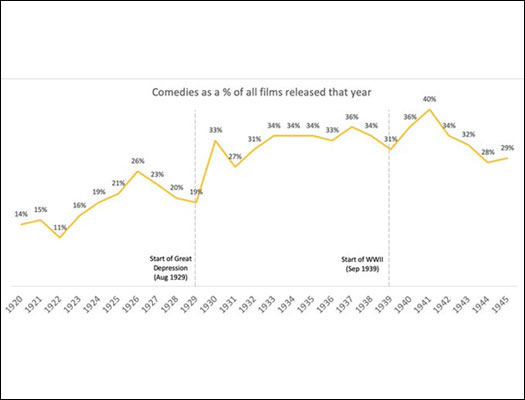

- Richard: Empathy is not believable. And actually, if you look at Hollywood's reaction to bleak times, that's exactly what you see. There was a wonderful bit of analysis of the IMDB database.

- MichaelAaron: Yes, this is deep. All the people that look at all the movies globally, I think.

- Richard: Yeah, exactly. Says thousands of movies on this. And I think it was Uncle Beau McCready looked over the last hundred years. What proportion of films have been comedies. And what you see is that real times of global problems, Great Depression, Start, World War Two. You see spikes in the proportion of comedies

- MichaelAaron: during Bad times. More comedy.

- Richard: Exactly. Because what you want, you want a bit of right relief to take your mind off all the the rubbish that's happening in the world.

- Richard: So Hollywood recognize the role of humor. I think advertisers are making a mistake by following a different path and thinking that it's, you know, seriousness and empathy, that that's what's desired.

- MichaelAaron: And, you know, I think the type of humor that you used is also really instructive because, you know, yeah, Snickers is using almost a self-deprecating humor. You're not you and your hungry is about you.

- MichaelAaron: It's about the person you become.

- Richard: Yeah.

- MichaelAaron: Versus so much of the advertising, especially in 2020 and 2021 with its serious important issues of racial justice and social inequality. Brands almost felt like I think they couldn't bring humor to the table because they would be off key to what the world was going through.

- Richard: But to me, that's a mistake about human nature.

- Richard: Even in the most bleak times. You spend all your time thinking about that.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: Event.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: Now we're thinking about much more mundane, trivial, personal issues most of the time.

- MichaelAaron: Yes.

- Richard: And that's the area I think adverts should play. Playing. You've got a reasonable role of a bit of light relief. I think that would always be very appropriate.

- Richard: You don't have to reference the dark things that are happening at the time. You, I think, are just present at those moments

- MichaelAaron: and especially being aware of your category. A candy bar plays a role of indulgence and relief. You know, it doesn't have to play the role of a moral entity all the time.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. And there is a lot of evidence that if you put people in a good mood, they've had a more like to notice charades.

- Richard: They're more like to believe them and they're also less price sensitive. So people need to move away from thinking the humor is something that's flippant and not appropriate for a serious business and recognize the humor can be a way, obliquely, of generating your underlying sales needs.

- MichaelAaron: You know, what strikes me about humor, Richard, is that it really is such a straight shot way to change the mood of the person receiving the humor.

- MichaelAaron: Right. It immediately either draws you to laughter, it immediately draws you to change your perspective. And that change of mood is critical.

- Richard: Yes, it might well be a fleeting change, but even that is enough for a commercial advantage. So there's a lovely set of studies from 2007 by Fred Bronner. So he's at the University of Amsterdam and he got 1287 people to flick through a newspaper.

- Richard: And then after they'd read through these papers, he asked them whether they were in a good or bad mood, and then he asked them to recall as many ads as they could. And if people are in a bad mood, they remember about 35% of ads. If I was in the good mood it was about 50% of the ads.

- MichaelAaron: Hmm.

- Richard: So you have an almost 50% improvement in recall based on someone's mood.

- Richard: Now, that's probably because the foul are temperament. The more your field of vision interest

- MichaelAaron: narrows.

- Richard: narrows

- Richard: Yeah well he showed that, you know, in the reverse if someone's feeling positive, they're much more open, much more likely to notice you. So that's one big benefit the movie brings. The second big benefit is around believability of message. So I reran a study a couple of years ago, five years ago, and rather than ask people whether they recall the ads, I asked them why they believe the ads.

- Richard: And I saw an even bigger uplift from the order of 60% improvement. So people who were happy believe ads about 6% more than those who were unhappy. Now, Daniel Kahneman argues there is an evolutionary rationale for this, that if we were in a foul mood, it signified danger and the need to think critically. If we're in a good mood, it signifies an absence of danger and mitigates the need to think critically.

- Richard: So if you want people to interpret your message without skepticism, either target them, then in a good mood or, as you say, put them in a good mood, have lots of very practical benefits to the use of something that seems as trivial as humor.

- MichaelAaron: I don't know if this is a divergence from what we're talking about here, but it often strikes me in pharmaceutical ads that, you know, they show people laughing and smiling and rowing boats on the lake or riding bikes in the mountains while they're describing some pretty serious side effects.

- Richard: Yeah, I mean, I think that said, to persuade, I think that's a confusion of telling rather than showing.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah.

- Richard: Just because you show someone that's laughing doesn't mean the view is going to laugh.

- MichaelAaron: That's right.

- Richard: Point is, you should tell them a joke and then they'll get positive and then they're more like to believe what you what you say.

- Richard: But they might feel like the really serious subjects. They've got to be careful in this area. But I think people go too far in the other direction. There's an amazing set of studies called the Ostrich Effect. George Loewenstein, who's a Carnegie Mellon, ran these studies and he works with Vanguard or an American fund provider and a Swedish equivalent.

- Richard: And what he shows is that when the stock market is rising, people check their portfolios reasonably regularly. But when the stock market declines,

- MichaelAaron: they don't want to overdo it.

- Richard: Now, exactly. They don't want to check. They don't want to find out the bad news. So his argument is, look, this is illogical. The information is equally valuable whether you're in a good or bad mood.

- Richard: But what he says happens is most people, if they're faced with an uncomfortable situation, they have two choices. They can either resolve the issue, but that's often hard work, or they can just ignore it. And the ostrich effect is the finding that we often would rather stick our heads in the sand. Metaphorically than go to the hard effort of resolving the problem.

- Richard: So if you deal with a serious subject and try and scare people into the interest or make them fearful,

- MichaelAaron: head goes in the ground.

- Richard: Head goes in the ground, they'll ignore the mystery. But if you can treat it with a little bit more humor, then you've got an opportunity to persuade. So one of the most successful public service campaigns ever in Australia was called dumb Ways to Die.

- Richard: And it essentially talks about all the ridiculous ways someone could end that and the like. You know, you can let yourself be eaten by crocodiles. It's a wonderful song. And the point of the song is at the end of it, the dumbest way to die is to go across the tracks on a metro and get hit by a subway.

- Richard: Horrible subjects. But they actually encourage engagement by dealing with it in a light hearted way. I think what most campaigns do is the complete opposite. They try to scare people. They try and shock them.

- MichaelAaron: This is your brain on drugs. I don't know if you that your campaign

- Richard: might win at awards, but it's often not the most effective change your behavior.

- MichaelAaron: So we've been talking candy bars, we've been talking comedy. We've been talking the power of triggers and cues. Let's wrap up today's episode with some lighthearted humor. I'm going to get us started, Richard. Why do behavioral scientists have such bad teeth?

- Richard: I have no idea.

- MichaelAaron: Loss aversion.

- Richard: Ah God

- MichaelAaron: All right. See if you can beat it. Go ahead.

- Richard: Oh, okay.

- Richard: I don't know any more behavioral science jokes about my mother. But my my favorite kind of academic joke is a classics professor walks into a tailor's, and the tailor says Euripides. And he says Humanities.

- MichaelAaron: (LAUGHTER)

- Richard: I think that I think we might escape the loss emotional that

- MichaelAaron: Euripides. And then you said what?

- Richard: Humanities. I think about what I think was funny.

- MichaelAaron: I don't know that

- Richard: Too Greek type of Greek.

- MichaelAaron: Exactly. So, Richard, as we'd like to do. Let's wrap it up for our listeners today.

- Richard: There are two big takeaways from today's podcast. The first is the principle of creating a cue or trigger moment. So that's based on the Sarah Millen work that we discussed. And it's the idea that motivation alone isn't enough.

- Richard: And what you need to do is combine desire for your product with a very clear time, place or mood that people associate with consumption or purchase if your product

- MichaelAaron: acts as a trigger.

- Richard: Exactly. Second key learning, I think, from today's podcast is the humor and jokes and funniness are not nice to haves. Even if you work in a very serious business.

- Richard: Think about how you can be a bit more lighthearted. There's an awful lot of viral science work that suggests it will boost recall, it will boost attention, boost positive feelings towards the brand, and probably most importantly, purchase content.

- MichaelAaron: Thanks for tuning in today to Behavioral Science for Brands Podcast. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: And as always, please come to us with ideas for new topics, new things for us to cover.

- MichaelAaron: Please visit us at TheConsumerBehaviourLab.com. Connect with us on social media or drop us an email at [email protected].

- Ad: Behavioral Science for Brands is brought to you today by Method 1–A digital-first marketing company that brings science to the art of persuasion.They’re behavior change experts who solve business challenges by creating meaningful connections with consumers. Method 1 has deep disciplines across many brand categories. To unlock behavior change that fuels brand growth - visit them at method1.com

Episode Highlights

Cue or Trigger Moment

The importance of creating cue or trigger moments to convert intention into action. An experiment by Sarah Mellon is mentioned, where participants who were asked to specify when, where, and with whom they would exercise were more likely to follow through.

Humor in Advertising

The use of humor in advertising, emphasizing its power to change mood, boost recall, and increase positivity.

The Ostrich Effect

The Ostrich Effect is a concept where people tend to ignore uncomfortable or serious subjects, highlighting the importance of using humor in messaging.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.