Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to the Behavioral Science for Brands Podcast. I'm Michael Aaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: Today we're talking How political campaigns have applied behavioural science to sway their audience. Let's get into it. So, Richard, our podcast title is Behavioral Science for Brands. But when you and I got together and we were designing season two, we said, wouldn't it be fun to go a little outside of traditional brand marketing and talk about how behavioral science can be applied to other things that you and I are passionate about?

- Richard: Absolutely. We've looked at an adjacent category, and I think often you can learn just as much from a related category as from your own category. And here we've been talking about politics. Behavioral science is just the study of how people behave. So, if you are ever trying to influence people, whether it's their personal life, whether it's politics, or whether it's purchasing, there is a role for this topic.

- MichaelAaron: That's right. And Richard and I share a great friendship, but we also share a great passion for politics across the pond. Richard's originally from the United Kingdom, lives there, and he and his family are there now. I'm from the United States and politics is very much a part of everyday life. So as Richard says, you know, the lessons of behavioral science can just as aptly be used as we think about how they apply to politics as any other part of life. But to make sure we don't get too political, Richard and I have said, how can we make this an inclusive podcast for the whole spectrum? So, we've chosen historical campaigns that we really love that we believe clearly teach behavioral science, and that might not be too polarizing.

- Richard: I think if we talk about the last election or the one before, the one before that, suddenly people get clouded by their own political viewpoint. If we go back 100 years or 50 years, we can focus on the principles the politicians are applying, not whether we agree with their approach to economics and society.

- MichaelAaron: That's right. And so often, especially in American presidential politics, they're looking to capture the moment that the country's in. And so as much as it's about messaging and communications and brand building of a candidate, it's also reacting to the mood and the emotion of, today, 350 million Americans, but tens of millions, hundreds of millions of people that are going to vote. And how do you capture that right moment? It's really a very challenging marketing and communications challenge that’s really interesting to unpack and go deep on.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. It’s a hugely complex product you're selling, in a way, that you've got to distill into often a few words as your message. So, if you can apply behavioral science here, if you can capture your essence in a few words, you can apply it in many other areas.

- MichaelAaron: So, Richard, let's take our listeners back, over a hundred years to Warren Harding's 1920 presidential campaign, and he uses a campaign slogan, “Return to Normalcy.” And when you hear that today, it almost hits the ear and it's just another phrase, but at the time, he really employed something that was unexpected and really changed the way people tuned into the message he was giving.

- Richard: Yeah, normalcy was not a commonly used word. Many people thought he was actually mistaken. Technically, it was a word, had been dictionaries for 50, 70 years, but it was very rarely used. What most people would've said would be a return to normality. It's a message that post-World War I tuned into, you know, the time and the moment. A lot of people didn't want to be involved in foreign entanglements. What's interesting for us though, is that specific choice of words, normalcy rather than normality. Now behavioral scientists would say the surprise of the word accounts for some of its power. If you go back to 1994, there was a psychologist called Michael Santos, and he ran a slightly bizarre experiment in which he dresses up like a beggar, goes out onto the street and ask people to give him money. Now, sometimes he asks for a quarter, he asks for loose change. This is how most beggars would ask for money, and when he does that, 23% of people give him some cash. On other occasions, he asks for 17 cents or 32 cents.

- MichaelAaron: Very specific.

- Richard: Very specific and also a surprising amount. Now when he does that, the proportion of people who donate goes up by more than 50%. You've got 37% of people giving cash. Now what's interesting here is Santos calls this the pique effect. P-I-Q-U-E, not the peak of a mountain. So, he argues that it's the surprisingness that makes the plea powerful. He says, when people are walking down the street, they have an automatic reaction when they're asked for cash. They have a script in their head, which is, if someone asks you for money, I'm just going to say no.

- Richard: They make their life simple by not weighing up the merits of the request, just having an automatic reaction. But Santos says, when the beggar asks for the money in a surprising way, it breaks that automatic, reflexive reaction and instead it gives people pause for thought. And the simple act of considering the request doesn't mean necessarily everyone will donate, but it increases the probability. You've at least captured their attention.

- Richard: And I think that's what this phrase “return to normalcy” did. It didn't wash over people. That little mistake, that idiosyncrasy of phrase, it stopped people in their tracks. And it at least got them to reflect whether they did want to return to normalcy or normality. So there's a lovely lesson there in the power of idiosyncrasy, in the power of maybe even a mistake in terms of language, but certainly the power of surprise.

- MichaelAaron: So, I went back and looked at the recordings of several of his speeches from the Nation's forum, and I just grabbed the words around this phrase. In a few of the different ways he presented it, and this one was most striking to me. He says, “America's present need is not for heroics, but healing. Not nostrums, but normalcy, not revolution, but restoration. Not surgery, but serenity.”

- MichaelAaron: So, he puts it in this, phrasing, this phraseology, where it really does hit the listener of 1920 in a different way. And remember, there was no television. They were only listening to this on radio. They were only reading this in print. And it really hits in a different way.

- Richard: Yeah, as a communicator, you cannot assume people's attention. I think that's a real mistake. But if you add in this into idiosyncrasy, you put a little bit of grit in your communication that stops people in the tracks, and at least they consider the point you are making. Now you've got around one of the biggest hurdles of any piece of communication, which is actually getting people to reflect on what you are saying.

- MichaelAaron: Great examples in brand work, Apple says, “think different.” Yes. Should have been-

- Richard: Think differently.

- MichaelAaron: Right. Heinz says Beanz Meanz Heinz.

- Richard: Yeah, right. You got a Zed in there, not an S. Both, if you are a pendant, you'd complain about, but in terms of this principle from Santos, they're applying that. They’re getting you to stop and think and consider.

- MichaelAaron: And one of my other favorite ones: from Adidas, instead of “nothing is impossible,” their tagline for many years, “impossible is nothing.” It makes someone stop and say, “wait a second, is that what they meant? Or did they get it backwards?” Same thing. So, let's head to break and when we come back, we're going to jump 40 years in the future to JFK and Nixon's presidential race, and we're going to talk more about that.

- MichaelAaron: Behavioral Science for Brands is brought to you today by Z-Axis Strategies. Through behavioral science and cutting-edge technologies, Z-Axis approaches public affairs holistically based on their founding principle: “politics should bring people together.” They change beliefs for the overall good, for good. To unlock behavior change that supports your political needs, visit them at zaxisstrategies.com

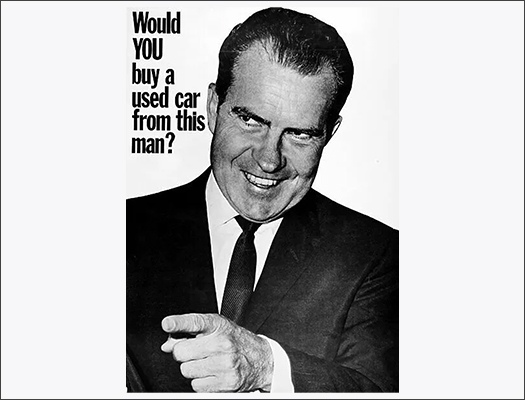

- MichaelAaron: And we're back. Now, let's fast forward. It's the 1960s presidential campaign between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. And to really get the power of this piece of political communication, you got to look at the show notes. Richard, do you want to describe what you're seeing on the page right now?

- Richard: Yeah. So, you are seeing a picture of Nixon, which probably isn't his most flattering picture.

- MichaelAaron: I would say not.

- Richard: It's slightly leering image and underneath it says, “Would you buy a used car from this man?”

- MichaelAaron: Right. And it makes you feel something right away, doesn't it?

- Richard: Yeah. I think this is one of the great lines in political advertising, and it works really well for two reasons. There's two behavioral science principles being applied. The first is involved with the audience. It is not telling you what to think. You are generating your own answer. That's of interest because in 1978 there was a wonderful set of studies from some Canadian psychologists, Slamecka and Ahluwalia into an idea called the Generation Effect.

- Richard: Essentially the idea that if you partly generate your own response, it is much more memorable than if you are told what to think. So, in their study, they recruit a panel of people, they split them in half. And one half get a list of, let's say, animal names: fish, dog, cat, elephant, rat. The other half get exactly the same list of animals, but when those words are written out, it would be c blank t or d o blank. People when they're reading through, it's obvious what the answer is, but they have to generate it themselves. When the two psychologists ask those groups to try and recall as many of the words as they can, The group who generated their own answer, remember 15% more words.

- Richard: The argument from the psychology is you have to put a bit of effort in. If you have to engage your mind, if there's a bit of processing that has to go into the answer, that creates stickiness, that creates memorability. So, the first thing I love about this ad is it involves the audience. They generate their own answer. They are going to remember that much better.

- MichaelAaron: And when you see this picture and you read these words, you can't help but answer. It pulls you into the ad, which is what you're saying.

- Richard: Yeah. So, you've got this - I think there's - the first bit is this memorability. That's the generation effect. The second one is, I think the really clever bit, especially maybe for political advertising, is the obvious thing to have done would've been, say Richard Nixon is untrustworthy.

- MichaelAaron: Right, straightforward to the point.

- Richard: Straightforward, but that sounds like very logical. The problem is some people hate to be told what to think. There's an idea called reactance. If you try and force someone to believe what you are arguing, you can often get pushback. You can often backfire. What this essentially does is get the audience to persuade themselves. And who do we believe more than ourselves? So, it's not just memorability, it's also believability of the message.

- Richard: Now, again, that's not just speculation. There is a lovely study from the University of Kansas, 2004. A psychologist, Rohini Walia shows people an ad for some fictitious shoes. Sometimes that ad ends with the line “wearing of anti-shoes can reduce the risk of arthritis.” Other occasions, there's just a couple of words at the beginning, “Did you know wearing of anti-shoes can reduce the risk of arthritis?”

- Richard: That simple, rhetorical question increases believability of the message by 14%. So, we are seeing in peer reviewed experiments this point around getting people to answer questions rather than directing them what to think can boost believability.

- MichaelAaron: You know, sometimes we talk about studies where it increases at 30%, 50%, and it's almost evocative, like, how could you not do it? In an instance where it's 14%. Wouldn't we say who doesn't want a 14% better chance of believability? Like why not take it if it's available?

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. You've got to pose a bit of copy in a certain direction. Do you do it as a statement or do you do it a question? Well, this would argue, especially in something maybe as contentious as politics, where it feels such an important decision, I think here the danger of reactance is amplified and letting people feel they've come to their own conclusion is much more powerful.

- MichaelAaron: And you know what else is interesting, Richard, even today, no one knows who wrote the line for this ad. And so, nobody has taken credit for this line. It may have been used in a popular song around the same time, but who actually came up with an ad that might have been just as impactful on voters' choice that has all of JFK's speeches of that election cycle. That’s pretty powerful.

- Richard: Yeah. Amazing that something so effective has never been recorded.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, never been attributed. Absolutely. All right, Richard, we like to end every episode the same way. What are the key takeaways we want people to have?

- Richard: Key takeaways are that behavioral science can be applied in an awful lot of areas. This isn't just something for brands. If you want to influence the behavior of people, whether it's their personal life, their politics, or their purchasing, you can use this field, and in particular, the ideas we discussed today are the power of allowing the audience to generate their own answers - that becomes more memorable. And then also the idea that we are much more likely to remember the surprising fact rather than the mundane. So sometimes paradoxically, making what seems like a mistake can boost memorability.

- MichaelAaron: Thanks for tuning in today to the Behavioral Science for Brands podcast. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: We're always looking for new topics, new ideas to cover on our podcast. If you have one, please visit our website www.theconsumerbehaviorlab.com. We have a form, fill it out, drop us an idea. Leave a comment on any of our social channels or email us [email protected].

Episode Highlights

Versatility of Behavioral Science

Behavioral science applies to many areas beyond brands. It can influence people's behavior in their personal lives, politics, and purchasing.

Return to Normalcy

The surprising and idiosyncratic use of language, such as Warren Harding's campaign slogan "Return to Normalcy," can capture people's attention and increase the probability of considering the message being conveyed.

Unknown Author

A memorable political ad from the 1960s presidential campaign between JFK and Nixon involved the audience generating their own answer to the question "Would you buy a used car from this man?", utilizing the Generation Effect and increasing believability through reactance.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.