Episode Transcript

- MichaelAaron: Welcome back to the Behavioral Science for Brands Podcast. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

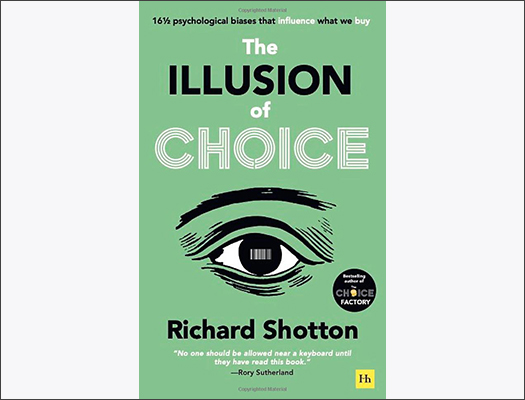

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: Today we're chatting How Facebook harnesses uncertain rewards to build a sticky user experience. We're profiling Facebook. Let's get into it. Richard, if there was a company that needed no introduction, I think Facebook would be high on this list. But to give it the proper opening, Facebook's founded in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg as a student at Harvard University. Originally, it was limited to Harvard students. It gradually expands to being available to other North American universities. And since 2006, anyone over the age of 13 years old can have a Facebook account. Fast forward to 2022, Facebook claims 2.9 billion monthly active users, ranked third worldwide as the most visited website, and was the most downloaded app of the last decade, 2010 to 2019.

- MichaelAaron: As of December 2022, Meta has a market cap of 562 billion dollars. This makes them the sixth most valuable company by market cap in the world. So, we've chosen Facebook today, because there's a lot of behavioral science behind how they have grown their brand and how they keep it so sticky today. Interestingly, when we were doing research on the founding, Zuckerberg was actually studying psychology at Harvard while he was a keen computer programmer.

- MichaelAaron: So, the idea of computer programming and psychology were likely intertwined. In a number of the initial social networking websites, he started for fellow students, Course Match, which was one that allowed people to view others' degrees and Face Match where you could rate people's attractiveness. One of his less popular ventures. But really, as we think about the behavioral science that powers Facebook, there's a lot to choose from, right, Richard?

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. I would argue that there's one thing that is at the very heart of their success.

- MichaelAaron: It rises above all the others.

- Richard: Yeah. And that is the power of uncertain rewards or the variability, that's the heart of the experience. So, you can look at this from one of two ways. You could say, as you scroll through your newsfeed, there's stuff that's just that really. And then every, so there'll be something that's very intriguing. There is a real variability to the interest levels of the posts that you read.

- MichaelAaron: I'm not just going to see updates from my friends and family, I'm going to see news articles. I'm not just going to see news articles, I'm going to see products I might want to buy.

- Richard: So, you keep on scrolling with the hope of getting that next hit of excitement. The other thing that Facebook has, which they were the first to introduce, was their like button. Now that introduces variability in terms of what you could see as the success of your post. Sometimes you post, you get no likes. Sometimes you get ten, sometimes you get hundreds, sometimes you get three. It's the variability that almost makes the product addictive. It's the uncertainty of the reward that you get from posting.

- MichaelAaron: And we would propose that if you could guess the reactions you're going to get, or if you could anticipate the response, it would be less likely to keep you coming back and keep you engaged.

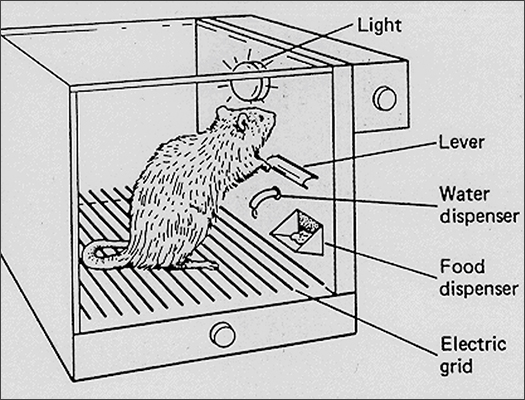

- Richard: Yeah. And again, what we've said before is one of the brilliant things about behavioral science is this isn't speculation. People aren't sitting in their ivory tower, looking inwards and arguing from logic alone that variability is the key to embedding a behavior. There are a range of studies that prove this point. Most fascinating, those studies aren't just in humans. If you go back to 1930, one of the world's most famous psychologists, B.F. Skinner, ran an experiment into the power of uncertainty on pigeons and on rats. So, Skinner was most famous for creating a thing called the Skinner Box. It's this box that you would put a pigeon in, and within the box there was a lever.

- Richard: A pigeon has no idea what a lever is, so it completely ignores it. But sooner or later, it bumps into the lever, and when it bumps into the lever, it's rewarded with a sugar drop. Skinner then leaves the pigeon in there, and this pigeon pumps away at the lever to get sugar. They love sugar. But once that habit is embedded, Skinner turns off the sugar supply and he monitors how long it takes until the habit evaporates, until the pigeon starts ignoring the lever and it's not that long.

- Richard: Another set of pigeons, they're put into a very similar box, but this time when they bump into the lever, sometimes they're rewarded with one sugar drop, sometimes two, sometimes three, sometimes nothing. Overall, it averages one sugar drop per push, but there's this variability within it. Again, Skinner follows the same process.

- Richard: He waits until the habit's embedded, and then he turns off the sugar supply and he sees a very different reaction. The pigeon keeps on pumping this lever for much, much longer. What Skinner argues is if you want to embed a behavior change, if you want to embed a habit really deeply, you need to use uncertain rewards. You need to introduce this element of variability rather than a fixed, certain reward every time someone behaves in the way that you want.

- MichaelAaron: So, let's apply it to Facebook. If you got the same response every time you posted content-

- Richard: It becomes a chore. Why would you bother posting all these photos if every time, the post goes green cause one person likes it? It's that number, it's that variation number, that makes it so addictive that you want to come back again and again and again.

- MichaelAaron: So, pigeons and sugar water, Richard. Compelling, and I mean, it's provocative. But are we making a little bit of a leap? Are we saying that just because an animal would do it, humans are not subject to the same behaviors?

- Richard: That's a fair challenge. And if it was just animals, I would agree. What's really interesting is you see it in animals and humans, and I think when you see a behavioral insight that straddles, different species, you know you’re onto something really fundamental to life itself.

- Richard: Now the study that shows it works in humans comes from 2014 and a psychologist called Luxe Chen. She recruits a group of people and she sets them a challenge. And I think it is drink three pints of water through a straw in two minutes. And if people succeed, she gives them $2. Now when she sets up her study in that way, 43% of the participants hit the time limit. They get the $2. Next group of people, Luxe Chen brings them in, gives them exactly the same challenge, but this time the reward varies. She says, if you succeed, we will flick a coin and you’ll either get $1 or $2, depending on which way the coin lands. Now, even though that on average is going to pay out less, or on average pay $1.50, even though the financial award is less, the impact on people, because of that uncertainty, is greater. We now have 70% of people achieving the goal, not 43%. Now, Chen explains this in the same way of Skinner, which is, it's not just the scale of the financial reward that matters, it's introducing a dash of unpredictability because then you've got two reasons to want to succeed: the excitement of the gamble and the financial benefit.

- MichaelAaron: So, this is really very interesting. Let's cut to a break, and when we come back, let's talk about how we can apply this to how marketers may use it for their brands.

- MichaelAaron: The Behavioral Science for Brands podcast is brought to you today by Function Growth. They are a team of direct-to-consumer experts and marketers who snap into brand-side teams and accelerate growth. And here's the best part. Function Growth leverages a shared risk and reward model. Which means they only profit when your brand profits. They have a proven track record of using behavioral science with some of the fastest growing direct-to-consumer brands in the country. To learn more, visit them at functiongrowth.co.

- MichaelAaron: And we're back. All right, we've covered some interesting topics. We've got pigeons, we've got sugar water, but let's talk about how we can use this idea of uncertain rewards beyond social media networks where we see it have a highly engaging effect, and let's look at other brands and how it's being used elsewhere.

- Richard: So, if we want to look at commercial example, I think loyalty schemes are a fascinating area cause essentially with a loyalty scheme, you are trying to build a habit. You’re trying to-

- MichaelAaron: We're having, we're having a UK-US disconnect. What type of scheme are we talking about?

- Richard: Oh, sorry. We do not say a loyalty scheme, a reward scheme.

- MichaelAaron: A reward scheme! A loyalty scheme, got it.

- Richard: You go to Starbucks, each time you get a coffee, you might get a little stamp on your card. You collect 10 of them, they give you a free coffee. Yes. Now that is what would be called a fixed or certain reward. You drink 10 coffees, you are guaranteed, by contract, you are going to get that freebie. Skinner and Chen would say, okay, that might change behavior, but it's not the most effective way of changing behavior. You want to introduce an element of uncertainty.

- MichaelAaron: Some variability.

- Richard: Yeah. Don't give someone that transactional reward after 10 coffees instead, like Pret a Manger, empower your staff to randomly give out coffees, you know, roughly to the proportion of one in ten. Not only therefore do you infuse your staff, you're giving them a degree of control, people will appreciate that product far more. And according to the work of Chen and Skinner, it's the uncertainty that will change their behavior more effectively.

- MichaelAaron: Hearing you talk about Pret and the random coffees that you can get without any knowledge brought to mind Isadore Sharp's book on the Four Seasons where he teaches how he wants all Four Seasons to operate.

- Richard: And he was this guy, the owner of the Four Seasons.

- MichaelAaron: He was the founder of the Four Seasons Hotel chain. And, I think he owned it to start. He creates this ethos that guests should have surprising moments of delight, and that each member of the staff is empowered to do that. Whether it's a bellhop, somebody who's a cleaning person, or somebody who's welcoming you at a front desk or at a restaurant, everybody's got charged with how can they create those unexpected moments? And when you read reviews of Four Seasons today, the comments are about “the staff were so amazing, they remembered this,” or “I never would've expected, and they did that.” And so it really creates a culture where they are creating unanticipated, uncertain rewards for people throughout their hotel stay.

- Richard: Nice. That fits a bit with another principle of behavioral science called the peak-end rule, which is what most brand owners do is they look at all the different touchpoints that they engage with a customer, and they think, how can we make them a little bit better? What behavioral scientists would say is that is an inefficient way of shaping memory. What you want do instead is pick one thing that you do expertly. The main thing people remember from experience is that single peak moment of excellence. P-E-A-K

- Richard: Yes. We had P-I-Q-U-E a while ago. This is P-E-A-K. So it's an idea from Daniel Kahneman and Donald Redelmeier and it argues if you want to shape people's memory of an experience, do one thing excellently, don't spread your efforts across lots of things, and secondly, end on a high, rather than start on a high. It's the final moment of experience you're particularly likely to remember. And I think that might fit with your Four Seasons example.

- MichaelAaron: Well, and it's nice to think about combining them. You want to have a peak moment - peak moment or an end moment - and you want it to be uncertain. If everybody knows they're going to get the same thing, it kind of takes away from this surprise and delight that you might have.

- Richard: Yeah, absolutely. So, you mentioned Four Seasons. The example I really like, it's very funny one, we'll put a little video. There's lovely case study of this. It's from Stockholm, Sweden, and they wanted to reduce the speed people were doing down a particular stretch of road. And their idea was something they called the speed camera lottery. So, like other speed cameras in the world, if you drive past too fast, you are given a ticket and you pay a fine. Rather than that fine money going to the government, what they did instead was put it into a giant pot. And anyone who was driving under the speed limit, when they went past the speed camera, they were entered into a lottery and they could win a proportion of that fine money. So, it's taking this principle of uncertain rewards and applying it to public safety.

- MichaelAaron: Yeah, public safety campaign. Okay Richard, like we do at the end of every episode, let’s wrap it up and give everybody the key takeaways from today's talk.

- Richard: The key takeaway is if you are thinking about rewards, you need to introduce an element of variability. Work on animals and humans show, we are much more likely to change our behavior if we are given a variable uncertain reward rather than a fixed uncertain reward. So, think about how you're dealing with your customers and can you inject a dose to randomness dose of variability into the rewards that you offer?

- MichaelAaron: And a pro tip that we can build on is if you do it as a peak or an end, you can take advantage of another behavioral science technique: the peak-end rule.

- Richard: Perfect.

- MichaelAaron: So Richard, we spent some time talking about Facebook. We talked about pigeons and sugar water, but what social media network are you most on right now?

- Richard: Okay, so most definitely not Facebook. Yeah, I have joined it, but I reckon I've posted 6 times in the last 15 years. So, Facebook, I've never really quite gotten into. The one that eats my time is Twitter. And now I love Twitter;

- Richard: I think it's a brilliant way for - if you've got a particular niche interest, like behavioral science, like advertising, follow the right people - and it is a wonderful mix of content. So, I spend quite a lot, probably too much time on Twitter.

- MichaelAaron: Well, you know, I've used social media a lot to stay connected with friends and family. We certainly use it a lot at business, but I would say I'm more of an observer on social than a poster. I would say I spend about equal time on Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, but it's all pretty minimal. Thanks for tuning in to this episode of Behavioral Science for Brands. I'm MichaelAaron Flicker.

- Richard: And I'm Richard Shotton.

- MichaelAaron: You know, Richard and I were talking, let's use a little peak-end effect right now. If there's anyone who would like to join us on the podcast, talk behavioral science, ask questions, learn or just jam, come and join us. Drop us an email at [email protected], and we'd love to have you.

Episode Highlights

Addictive Variability

Variability or uncertainty in rewards is a key factor in embedding a behavior and making a product addictive such as scrolling or posting on Facebook.

Pigeons & Sugar Water

Skinner's experiment with pigeons on the power of uncertainty suggests that uncertain rewards are necessary to establish a lasting change in behavior.

Peak-end Rule

Study conducted by Kahneman and Redelmeier states that when we look back at an event or experience, our recollections and opinions are heavily influenced by what happened at its peak intensity and its end.

Resources & Useful Links

Want to dig deeper on the idea of social proof and the intention of actions gap? Here are some

additional resources that show how to make your brand more popular with consumers and the

importance of combining motivation with triggers to convert intention into action.